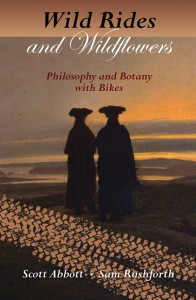

By just mentioning death camas (a plant known very well especially by Western sheep ranchers) in their new book ‘Wild Rides and Wildflowers,’ two Utah Valley University scholars lead readers to several epiphanies, as they recount four years of press columns they wrote about riding the Great Western Trail on Mount Timpanogos.

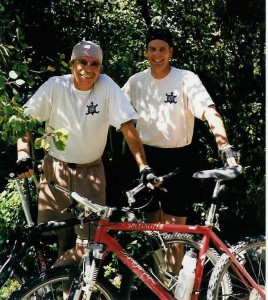

The plant becomes an opportunity for Scott Abbott, a professor specializing in German arts and letters, and Sam Rushforth, who has studied aquatic botany and wetlands ecology, to deal with issues extending well beyond the shadows of the ivory tower.

“You’ve stumbled onto something controversial and interesting here,” Sam says. “It’s a classic disagreement between the lumpers (me included) and the splitters…Lumpers see splitters as scientists who proliferate species endlessly on the basis of insubstantial differences. Splitters see lumpers as scientists who are too lazy or conservative to pay attention to the importance of details.”

Abbott later explains, “I bought these guides expecting scientific facts. Instead, I get judgments, assessments, interpretations built on biases. ‘Truth,’ Nietzsche wrote, ‘is a mobile army of metaphors.’ I’m fifty years old and have known this for decades. Now I know it again.”

Rushforth answers back: “Truth is relative for folks comfortable with dissent and argument, but solid as concrete among ideologues.”

Their book, published by Torrey House Press, is a new entry for a growing and worthy canon of the Utah Enlightenment, a period that is bringing forth some of the most compelling and powerful literary voices that direct readers to reconceptualizing and reimagining what it means to live in the American West and to challenge and remake the institutions that are failing to sustain their relevance.

Shedding the traditional skins of ‘publish or perish’ to reframe and reinvigorate the scholar’s penchant for philosophizing, Abbott and Rushforth have curated and compiled their work which ran for four years, most of it in The Catalyst monthly magazine, into a highly versatile, smart, entertaining, incredibly informative book for readers of all ages and interests.

Their literary counterpoint and harmonizing are as humorously engaging as they are elucidating. At the outset, Abbott might appear to be the more natural of the two in writing the column perhaps because of his own scholarly bailiwick. However, Rushforth learns one of their early columns appears in the same issue as a piece by Terry Tempest Williams (‘A Letter to Edward Abbey on the Tenth Anniversary of His Death’) – in which she makes the reference to a new species called Biker lycra siticus. Rushforth says, “And I’m taking over half the column. This is too important to leave to your misperceptions and sorry lack of talent.”

Williams was referring to the encroachment of mountain bikers and the potential threat to the natural surroundings, but the authors recall a letter by Ken Sanders (Salt Lake City bookseller and rare books specialist) who reminds that Abbey had a mountain bike: “After observing mountain bikes and their damage, near Arches, Wendell Berry remarked that riding mountain bikes is a ‘hell of a lot of work to go to, just to give your ass a ride.’” Rushforth adds that Abbey’s own ‘shit-eating grin’ is motivation enough to take on the enterprise, as rider and writer.

There was one other lesson from the mention of death camas. Abbott had misspelled the plant’s name as “camus.” As Abbott recalls, “Sam asks why it got changed after he had it corrected. ‘How the hell did it get back to the French existentialist?’” Abbott responds: “Must have been a subconscious indication of how I view your intelligence, or maybe the ‘death’ part of the name triggered the existential part of my brain.”

Rushforth warns Abbott: “You’ll have to promise not to amend botany with philosophy in the future.”

Yet, the prominent intertwining of their well-developed instincts appear to make many of the book’s frequent high marks and their individual capacity to turn wonderful phrases as well as to reveal most intimate parts of their characters and souls. Curious about the silver lupine plant with blue upturned flowers and ‘stalks heavy with hairy green pea-like seed pods,’ Abbott looks up the plant in a scientific guide, momentarily disappointing to see the scientist’s predisposition for unmistakable language. He writes, “It’s the off-putting language of a heartless classifier, I think defensively. Not a mention of how deeply moving that blue is as it rises from the silver-green fans of leaves. Then I correct myself. It’s our job to gush and quiver. It’s Welsh’s job [Stan Welsh, A Utah Flora] to see the lupine through the language of precision.”

Abbott later wonders if our compulsion to classify is a biological adaptation. Rushforth agrees but also notes how troublesome it can become. “Obsessive-compulsive disorder-my major day-by-day nemesis- may stem from something like an exaggerated need to classify.”

The book follows the rhythm of life – the moments of joy and laughter along with the poignant occurrences of sadness and absences – just as they track changes of season the two bikers chronicle during their rides on the trail.

Looking to soothe “crotch rot” in the middle of the night, Rushforth reaches by mistake a jar of theatrical stage blood instead of an athlete’s foot salve. After doing a double-take when he looks in the mirror in the morning, he adds, “When the final curtain isn’t too far away, something like this makes a guy wonder and whisper a little prayer of thanks for the safety of his testicles.”

When pressed about everything being true in their columns, Abbott tells a former newspaper editor that, indeed, they are. “The only exceptions are the statements about our potency,” he adds. “They, you should know, are always understated.”

The flesh and soul of both writers come through in many channels. Abbott and Rushforth make the transition from the Mormon educational citadel of Brigham Young University in Provo to the state’s newest public college, Utah Valley University in Orem. Abbott also is making the transition after a divorce. Rushforth sees ahead to the inevitable passing of time at an ever-quickening pace.

Returning at one point to the earlier discussion about lumpers and splitters, Rushforth recalls a 1996 essay by Abbott noting that the then-new BYU president Merrill Bateman plagiarized his whole diatribe against moral relativism. Abbott explains, ‘He’s right. If we have our way, the university will be at the mercy of immoral advocates of academic freedom. But enough of that. Let’s ride on up the hill.”

With barely a pause in the beat, they switch gears. Soon it’s “spring beauties spread across whole meadows still matted from the snow,” the joys of riding up through a “leafless maple grove” and finding the bright yellow color of Nutall’s violet.

Writing about the last summer solstice of the millennium (the column began in 1999), Rushforth, riding alone while Abbott is in Europe, offers up a beauty of elegant rhythm:

“I’m on the trail the very moment the Earth begins to tilt back toward the north, shortening the days in the Northern Hemisphere. I ride into dark black thunderheads on Timpanogos. Light slants under the clouds. A bit of rain blows hard from the northwest, silvered by the low sun. Birds are everywhere. All of the spring’s players sing for me, one by one, as I ride along. It is as though the spring birds take a curtain call and prepare for Act II, Summer.”

Readers are treated to all sorts of fascinating scientific information in the most plainly understood forms. Grass glistens in the sun because the epidermis contains silicon that “flashes the sunlight back at us.” The presence of fox scat is marvelously explained: “A lack of concern for the message suggests plenty about the messenger. As if on cue, a magnificent bushy creature, broad-shouldered, golden and glowing in its winter coat, flying a glorious white-tipped tail, moves like a sine wave across the adjacent draw. And then it’s gone.”

There also are plenty of instances where the threats to nature are presented as more complex and multifaceted than what the general public and certainly an ill-informed legislature would believe and claim. The seemingly most inconsequential details in the eyes of a novice or amateur gain urgent currency for the expert observer. Abbott and Rushforth join wildlife biologists from BYU who are trying to pinpoint the causes and extent of the attacks on sage grouse, which is being reviewed for a possible listing of endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Take note that their writings are more than a dozen years old. Finding a “slick tarry deposit of night feces” is revealing. Abbott and Rushforth recall what one of the biologists said: “Look at the fox! Close to where a sage grouse has come in for a landing, a red fox dances up the ridge. We cross the ravine and find a honeycomb of fox dens on the ridge. ‘This is worse than I feared.'”

The book’s candor is exemplary. Abbott recalls a public reading, in which Rushforth felt uncomfortable, especially because much of his writing is intensely private. “It was no accident that Sam read about his inner life and I read about bike crashes,” Abbott explains. “Biking has helped me avoid some lurking demons, but it can’t be good psychological strategy to sublimate what will, at some point, demand its due.” However, in the end, while he “would prefer a full Freudian analysis, he is quite at ease with his gear-headed, botanical therapist.”

Readers also are introduced to spouses and family members. Abbott’s son, Ben, makes several memorable appearances in the book, first as a teenager joining his father and Rushforth on the trail rides and later as a student at Utah State University where he decides to forgo traditional student housing and camp out in the open (incidentally, Ben is now pursuing his doctorate in Arctic biology at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks). Ben has a peculiar knack for the right punch line.

As Abbott recalls, “Down we ride, Ben twice as fast as I. At one juncture, I try to explain to him the need for caution.”

“Sure Dad,” he says. “I read your column.”

“You don’t believe all that stuff, do you?” I ask.

“Just the stuff about your virility,” he says.

Later, after Abbott is recuperating from a torn ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), Rushforth, who is facing a colonoscopy, said, “but there’s no such thing as a sympathy card from our editor saying HOPE YOUR ASSHOLE IS OKAY.” Leave it to Ben to follow up: “True. That’s the card they send to your wife.”

There is one exceptional moment that particularly amplifies Abbott’s portrait and a legacy that will surely be sustained. Abbott shares a letter from Ben, at Utah State University in Logan who carries all of his belongings with him to class and is living “closer to a true homelessness, just what I wanted.” As one class ends, he recalls the following:

“‘Wow, heavy load,’ my teacher said as I lumbered out class with my thirty-seven-pound pack. ‘Not nearly as heavy as all the things you tie yourself to,’ I answered.”

Following an entry that features an excerpt by Herman Melville, Rushforth says that while they can’t write like Melville, it is worth asking those “knotty questions” about intimacy, competition, mundanity, and machismo, among others. “Better to ask them in print than to reach for a gun,” he adds.

And there are moments when the prose is elevated to memorable power. Contemplating the inevitable course of action the country will take in the aftermath of 9/11, Abbott looks to flowering rabbitbrush: “Fertile and hopeful and golden and pungent as hell. That’s my ideology.”

It is Rushforth who brings full circle the meaning of the rides and columns that were inspired by their many trips on the trail:

“And we have found pattern and order. We have seen the resurrection green of spring and the waning of the green season to the umber and barrenness of autumn. We saw the entire mountain burn and rode the next day through smoke, ash, and destruction and finally, months later, through growth and regeneration. And it has mattered, or at least has seemed to matter, or at least has seemed to matter to us.”

There is no doubt the book should matter a great deal not just to a Utah audience but to anyone who is concerned about preserving the greatest legacies the West has given us.

The book is available at many bookstores including Ken Sanders Rare Books, The King’s English Bookshop, and Sam Weller Book Works.

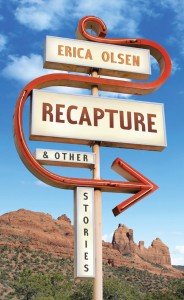

A nice little companion to ‘Wild Rides and Wildflowers’ is the 2012 anthology by Erica Olsen titled ‘Recapture and Other Stories.’ Olsen, who lives in the Four Corners area and handles archival and curatorial work for various archaeology museums, has compiled a collection of 16 short stories that strike the reader for their crisp unsentimentality and abundant source of darkish humor.

One of the standout pieces in Olsen’s tightly written anthology is ‘The Curation of Silence,’ which happens to sit right in the middle of the book. The centerpiece theme is well articulated here:

“Now, silences have fallen out of fashion. In the future, we may invent other means to consider and commemorate our vanishments. One day our museums may lose their function, and the architecture may puzzle our descendants. One day we may return to the ideal once represented by the cabinet and the jar.”

Many of the stories happen in Utah, especially in the southern half of the state, and at times I find Olsen amplifying persuasively themes that underlie ‘Boomtown,’ an award-winning short film by Torben Bernhard and Travis Low as part of their Lost and Found Series. It was a documentary about Frisco, Utah, a town that went ghost after a short but spectacular mining boom. Likewise, in ‘Recapture,’ we must be consistently mindful of how these memories can be erased so easily and lost forever. Otherwise, our reconstructed histories end up as neatly patterned comfortable artifices that eschew precisely the type of critical thinking and immersive contemplation Abbott and Rushforth engaged in constantly on the Mt. Timpanogos trail.

Disclosure: The Utah Review received free review copies of the titles in this review.

What an honor to have someone read this carefully and write so well about the book. Thank you!