Earlier this year, playwright Morag Shepherd directed the excellent Pygmalion Theatre Company production of Debora Threedy’s Mountain Meadows, which was about historian Juanita Brooks’ search for the truth behind the Mountain Meadows massacre, one of the darkest stains in Mormon history.

With news of the massacre, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints institutionalized a doctrine of obstruction, where the suppressed truth eventually becomes its own lie. It is a doctrinal practice that has been perpetuated seemingly through every scandal and stain connected to the church. In Threedy’s play, the character of Brooks responds to a church elder who says that not talking about it might be best for everyone concerned and that nothing can change what happened so the dead should be allowed to rest in peace. Brooks replied, “It’s us who can’t rest in peace.”

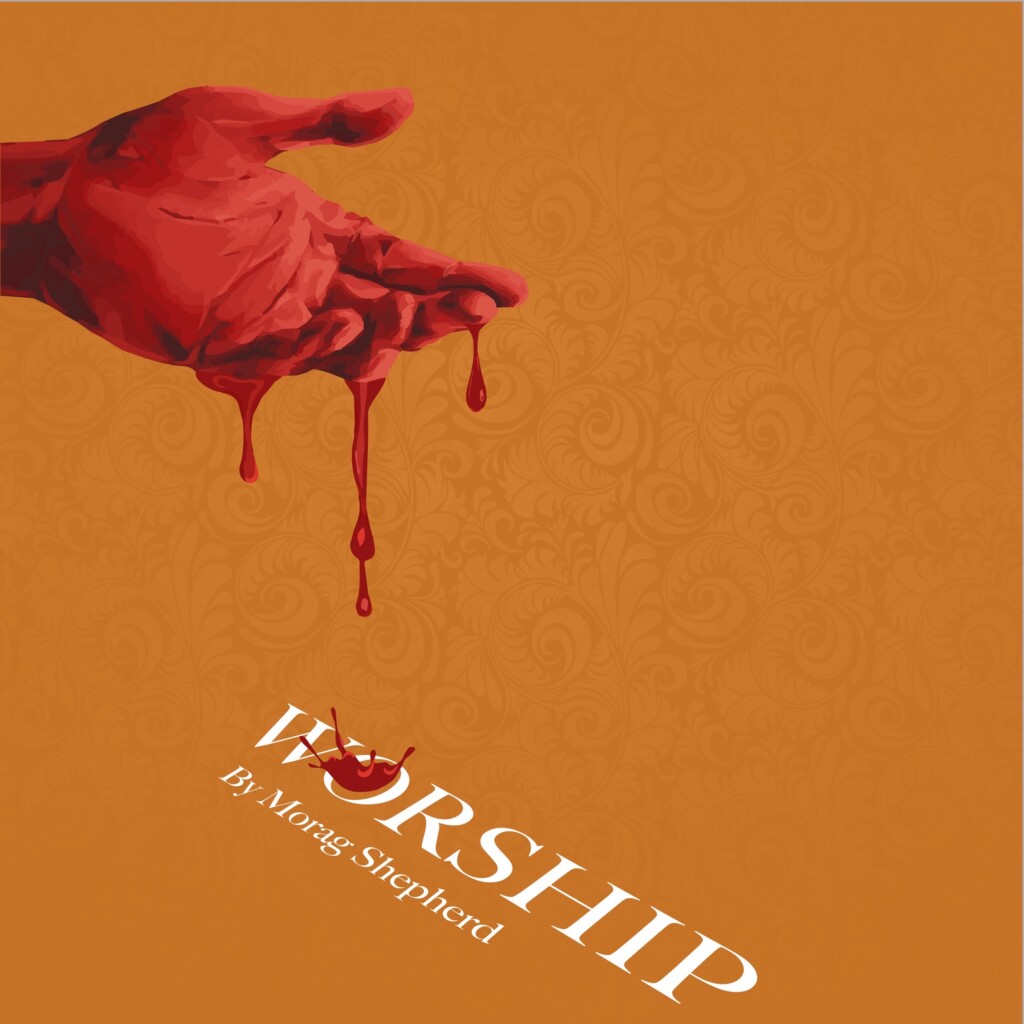

This month, Shepherd’s play Worship has become the essential contemporary companion piece to Threedy’s work, in an exceptional premiere produced by Immigrant’s Daughter Theatre. Directed by Stephanie Stroud, the tightly written play comprises four tableaus, with a cast of five actors.

In the hands of another playwright, the script likely could have been an unconstructive polemic, tying the sole male character in her narrative, Mason (Nick Mathews), to Joseph Smith, the church founder whose own history of dangerous sexual predation continues to be denied by LDS leaders, despite evidence otherwise. But Shepherd, who has been out of the Mormon faith community for quite a while, continues to contemplate how and why she feared for so long becoming uncomfortable and even avoiding the risk of being ostracized as an enemy or adversary, if she would have pursued questions proving whether or not what the church says is true.

In Threedy’s play, Brooks, who remained steadfast in her faith, knew that the only way to get to the truth was to become uncomfortable. In Worship, Shepherd also is wisely careful not to belittle members who believe in the church. But, she also infuses the stage atmosphere with a distinct air of discomfort, to the extent that it becomes lucid for anyone to comprehend, regardless of whether or not they were ever part of the Mormon faith community.

We are left with some characters who assuredly are struggling or will do so eventually, regarding their fears in probing their faith and ties to the Mormon community. They might end up wondering what happens if the probability is high that what they will discover confirms that the church leaders’ attempts to protect their claims as true collapse entirely under the weight of scrutiny and skepticism.

Shepherd, in part, was motivated to write the play when news broke three years ago about Michael James Clay, a former geography professor at Brigham Young University, who was charged with felony sexual battery charges after three students came forward with detailed accounts about abuse he had committed. Earlier this year, the case was decided when Clay took a plea bargain in exchange for the charges being reduced to misdemeanors. He was sentenced to 24 months of private probation, 50 hours of community service, enrollment in a sexual boundaries program and was ordered not to engage any contact with the victims. Civil litigation is still possible. This particular case serves the basis for the second tableau in Worship.

In the opening tableau, we have Mason and Chloe, his 12-year-old daughter (Ainslie Jane Shepherd, the playwright’s daughter making her professional stage debut). Chloe is a happy child. She studies violin, engages playfully with her father, and shares a dream she had about the savior chasing her in a shopping mall. She feels comfortable enough with her father to confess that she lost a gold watch that belongs to her mother. The acting is smart: the father is tense and uncomfortable but he also is careful to be discreet and noncommittal because he does not want to distract his daughter’s ebullient innocence.

In the second tableau, Shepherd is scrupulous about conveying the gravity of the actual circumstances which frame this scene, without it becoming gratuitous or exploitative for dramatic effect. In fact, its understated tone naturally heightens the sense of discomfort, especially if we recall that the record of the actual case was so graphic and disturbing in the magnitude of abuse that the judge who presided at Clay’s hearing noted accordingly.

Mason meets with Mary (Brynn Duncan), an undergraduate student at BYU, who is concerned that their relationship and the texts they have exchanged might have crossed the line of propriety in the teacher-student relationship. Shepherd latches onto an underlying emotional dynamic in this scene that church leaders know has been a successful strategy for them. Remember recent statements by Dallin Oaks, the first counselor in the church’s first presidency, which suggest that he is less concerned about persuading young people to convert or reinforce their beliefs than he is about making current members see the problem is not based on what the church claims to be true that can, in fact, be demonstrated to be false but that instead today’s young people are victims of easy temptation who are vulnerable and impressionable and willing to stray from their faith.

Meanwhile, the power relationship is flipped in the third tableau, with Flora (Renny Grames), a sex worker who understands completely why Mason, who feels so imprisoned by the social stigma and shame that is part of his faith contract with Mormonism, enjoys coming to her. Deep down, Mason yearns to be liberated and to embrace his anarchistic side but he fears the social price that he would have to pay for doing so. Of course, he is so desperate that he walks the high-wire of dysfunctional behavior that if he fails to cover up could risk him losing everything in his life. He already knows that the church could never deliver the salvation or reconciliation with his ‘celestial’ soul that its leaders have promised to unquestioning believers.

The final tableau features Emma (Ariana Farber), who is Mason’s wife. Her suffering is metaphorically grounded. It is in this scene where Shepherd has subtly tethered the history of Joseph Smith’s first wife to the script for Worship. Historians have consistently outlined the conundrums and dilemmas Emma Smith confronted in trying to reconcile her private reflections about her husband’s polygamous practices with public statements where she spoke against polygamy but also denied the extent to which her husband practiced it. Since then, church historians at the behest of generations of LDS presidents have threaded the needle so many times to rewrite the narrative suggesting that Emma eventually reconciled her concerns about polygamy with the ecclesiastical doctrines her husband had set forth.

This is why Shepherd’s Worship and Threedy’s Mountain Meadows unite as relevant companion theatrical pieces to comprehend the current state of Mormon affairs. These are playwrights who know how to take the current temperature in the Land of Zion. Setting aside the BYU abuse case for the moment, these two plays are elucidating for those who are learning about the ongoing sex abuse scandal and subsequent ostracization surrounding Tim Ballard, a prominent Mormon. Before the scandal broke out, his story as a rescuer of children from sex trafficking rings became the basis of the sleeper film hit Sound of Freedom. When the scandal broke, some of the most devastating details came through Blaze Media, which is operated by Glenn Beck, a former supporter who has said that he still cannot believe that Ballard had duped him. Blaze Media reports reveal details that unfortunately parallel the provenance of the circumstances referenced in the play. Ballard used tactics of spiritual manipulation to coerce women into engaging in sex in order to help children who were the victims of trafficking. The report alleged that Ballard would persuade them by asking if they were willing to do anything to save a child. Ballard said that this was acceptable, citing Book of Mormon scripture that sometimes a man must kill another, especially if the Holy Spirit commands it. Among other perverse complications in this story is the fact that Ballard had been close to one of the church’s most senior apostles (who share the last name but are not related).

There is no question that the church knew about Ballard and almost certainly the accusations of sexual abuse against him. Previously, they heralded Ballard’s organization, the Operation Underground Railroad he once ran. But, when Ballard announced before the scandal hit that he was planning to run for a U.S. Senate seat next year, the church leaders engaged in a rare display of smashing him down when news of sexual abuse leaked.

What stands out in the Ballard mess is how many loyal Mormons could not fathom that church leaders were so quick to throw such a prominent figure under the bus. It is an ironic twist. Consider when someone challenges the church’s claim to truth: for example, the written testimony from women that documents just how extensively Joseph Smith was having sex with women other than his first wife, all while Smith rationalized it as a command from the heavenly father. The usual response has been either that the church’s founder never did it or, yes, it happened but now enemies and adversaries of the church are twisting the truth because they only care about undermining the church. With the Ballard story, the tables have been turned in an extraordinary way where the faithful cannot believe that church leaders would quickly dislodge one whom they had previously spoken of publicly with pride.

In Worship, Shepherd pulls the curtain back in these four tableaus, with understated dramatic force. In the final tableau, Mason and his wife Emma are, in some respects, behaving exactly as how the church prefers to see among its members. That is, they might be aware of problems but they still believe, because their only sources for their faith are those who stand steadfastly behind the church doctrines.

Shepherd’s counterpoint comes through the characters of Chloe, the daughter; Mary, the college student and Flora, the sex worker. Church leaders will insist that young people leaving the Mormon community have been contaminated by anti-faith teachings. Leaders are fully aware of a landscape where skeptics looking for information realize how little of what they were taught to believe is true. This is why Oaks and other church leaders push the argument about the young flock being led astray. It is practically the only way that the church can keep a sense of confirmation bias intact in its membership.

The actors succeed wonderfully in handling a complex set of nuances in the script. Per usual, Shepherd conceives her work for accentuating themes in compact, intimate spaces that immerse the audience from the opening scene. In this Immigrant’s Daughter Theatre bare-bones production, in partnership with the Utah Arts Alliance, the staging takes place in a space that resembles a church meeting room, with the small audience (maximum 25 persons each performance) sitting around the perimeter and observing the action taking place barely a few feet in front of them.

The venue is located at the SLC Arts Hub at 663 W. 100 South in Salt Lake City. The run continues through Oct. 21, with performances on Fridays and Saturdays at 7:30 p.m. For tickets and more information, see this link.