Come, all ye workers, from every land,

Come join in the grand Industrial band.

Then we our share of this earth shall demand.

Come on! Do your share, lend a hand! – Joe Hill

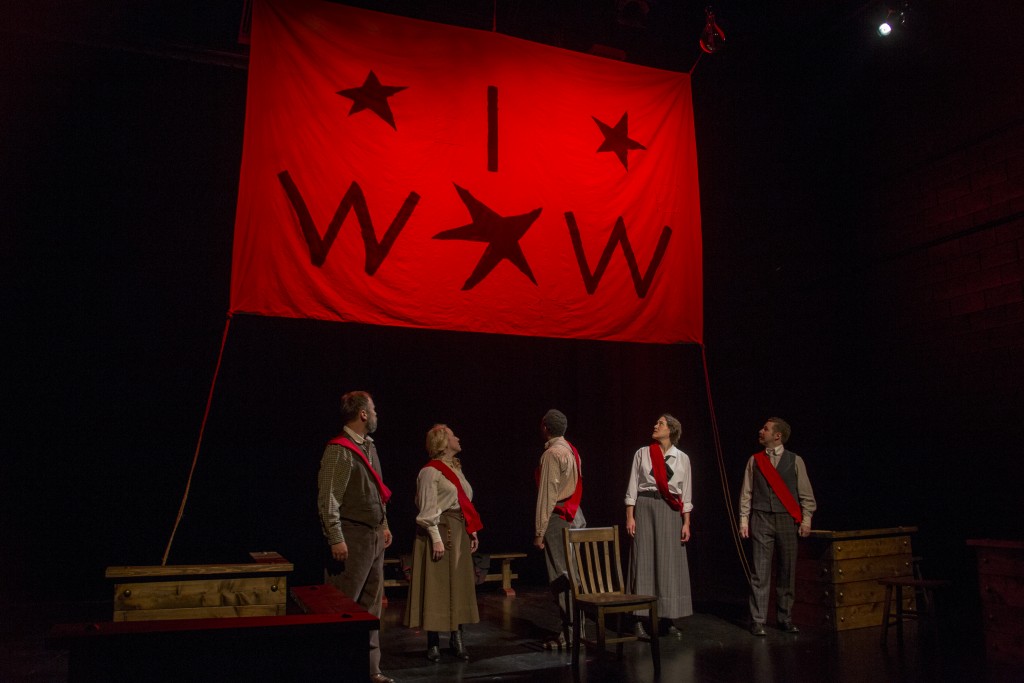

At the beginning of One Big Union, the cast of six actors walks through the audience, welcoming members to the evening’s gathering in the minimalistic yet unmistakable setting of a union hall. The simple, informal gesture immediately sets the tone for a play that now appears more consequential than four years ago when its playwright began writing it. Two nights earlier, many Americans were jolted out of their comfort and complacency by the presidential election results.

There are many prescient moments of contemporary relevance in the play, which chronicles the true events of a Swedish immigrant miner, musician and union activist who was executed 101 years ago in Salt Lake City after being wrongfully convicted of murder.

Joe Hill’s final exhortation that quotes the note he wrote his supporters just before his execution – “Forget me, and march right on to emancipation. Don’t mourn: Organize” – was the same message U.S. Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minnesota) tweeted just minutes before midnight last Tuesday. Ellison, a black, Muslim member of Congress who is being considered to lead the demoralized Democratic Party’s national committee, added, “And keep organizing. And don’t stop.”

Plan-B Theatre consistently has the uncanny ability to makes it original socially conscious work as serendipitous and urgent as possible. Debora Threedy’s One Big Union, directed magnificently by Jason Bowcutt, packs a wallop that may be one of the most memorable and consequential among the scores of world premieres the company has put forth in the last dozen years.

One Big Union achieves effectively a creative adaptation of Hill’s life that should appeal to theatrical companies across the country. The play’s sociopolitical and sociocultural themes can resonate anywhere and the storyline synthesizes the egregious errors of Hill’s trial and the seminal legacy of protest songs that inspired a new way of propagating the labor movement’s political punch.

The cast excels at every performing task. Roger Dunbar, who brings an eerily familiar resemblance to Hill’s appearance as we can see from archival photographs, rejuvenates the man’s political and musical legacy with incisive impact and excellent musicianship. However, while Hill is the central character, Dunbar’s ensemble work is the most notable aspect of his performance. He never overwhelms the stage nor the presence of the other cast members, who remain on stage throughout the 80-minute show.

To wit: Carleton Bluford’s performance of the Working Stiff, a union ‘Everyman’ who serves as the chorus of the play, succeeds at elucidating all of the right background and narrative markers that Threedy brings to her script. As Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an activist with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW a/k/a the Wobblies), Tracie Merrill provides the perfect counterpoint as a firebrand to the finely understated moments of Dunbar’s rendering of Hill. With Jay Perry, April Fossen and Daniel Beecher rounding out the cast, the ensemble handles masterfully the musical and choreographed demands of the production. These actors again remind Salt Lake City audiences how deep the talent bench is at Plan-B Theatre.

David Evanoff, music director, and Stephanie Howell, choreographer, deserve special recognition for bringing out the magnetic effects of these songs that gave IWW its organizational vitality. There are the vaudevillian tones of songs such as Casey Jones, the Union Scab. There are fine renditions of The Red Flag set to the tune of O Tannenbaum, or the plainly satirical message of Long-Haired Preachers, sung to the tune of the classic 19th century Christian hymn Sweet Bye and Bye.

The songs are hummable and memorable – just as Hill believed how they were essential to protest and rebellion. Threedy, a law professor whose plays always blend effectively the challenges of historical inquiry with the artistic demands of compelling theater, quotes Hill directly at one point: “A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read but once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over.”

Hill’s lines are tight and economical. There are no lengthy or stirring soliloquies. The greatest share of extended lines in the play goes to the Working Stiff. He provides plenty of details about the crimes, casting doubts on circumstantial evidence and eyewitness testimony. He also guides the audience to realize the events of that wintry night of 1914 in Salt Lake City never will be reconciled to anyone’s satisfaction – including the victim’s family descendants or activists and unionists who carry Hill’s legacy to this day. As the Working Stiff says:

There is a non-conspiracy explanashun for what happened to Joe. Pipe-smokin’ professor types, who sit in their libraries studyin’ this, say the convictions of innocent people tend to share certain characteristics. And Joe’s case has a lottof ‘em. A high visibility crime. A rush to judgment. Eye witness testimony. Police misconduct. A defendant who is an outsider, who belongs to some unsavory group. And inexperienced attorneys.

While Hill insists that he does not want to be a martyr, his execution secures that status. Flynn tries to persuade Hill that he could spare himself from the firing squad. She tells him, “The murder of the poor grocer and his son had nothing to do with labor. But accusing you? That has everything to do with labor. With who you are.” Joe says that he was the ideal candidate to be the scapegoat in the case – “because I wasn’t from here, just a dumb Swede and a drifter, as good a scapegoat as anyone.”

For many decades, Hill’s story was forgotten, mainly because few saw any historical relevance or connection to contemporary times and issues. In the last few years, as mentioned in The Utah Review’s preview of One Big Union, Hill’s story and music have been resurrected in prominent books with positive reviews. There also is a one-man show about Hill’s music by one of the country’s best-known folk musicians (John McCutcheon).

However, even as the legal travesties of Hill’s story make good material for theater, Threedy’s play reminds of the power of the protest song that animated the growth of unions – especially the Wobblies phenomenon during Hill’s life and certainly after his death. Hill’s funeral and rally drew tens of thousands, as many as both of this year’s major presidential candidates had at their rallies in the campaign’s closing days.

Unions no longer enjoy the political power or impact they once had but they have survived and there may be a resurgence in the next few years amidst an unprecedentedly chaotic, disturbing and dire political environment. The Working Stiff asks the right questions about the Wobblies and why they were so vigorously persecuted and hated. He says, “If you ask me, it was because they were the most radical union ever. They opened their doors to everyone, and I mean everyone. … If the Wobbly brand of radical equality had caught on, can you imagine what the world would be like today?” Those questions suddenly carry a piercing relevance in the aftermath of last week’s elections.

The IWW, which marked its 100th anniversary in 2005 with 5,000 members (as opposed to the AFL-CIO’s 11.6 million), has grown in the last decade, especially as some members believe that organizing workers for broader solidarity might be more effective than the traditional contract union model. In the U.S., Portland, Oregon is one of IWW’s largest branches. IWW’s global presence also is growing with branches in Australia, Austria, Canada, Ireland, Germany, Uganda and the United Kingdom.

One of One Big Union’s most fascinating discoveries is the positive epiphany arising not from nostalgia but of an optimistic belief that a movement of workers could spread the gospel of a more humane, dignified, respectful quality of life. The plays of workers’ theaters during the 1930s contrasted significantly with the pessimistic writings of authors including John Dos Passos and John Steinbeck. Many scholars have commented on how the plays during that decade paved the way for some of the mid-century’s greatest works by Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller and others.

A tremendous addition to the blossoming canon of the Utah Enlightenment, One Big Union adds another jewel to a glittering gem-studded crown honoring Plan-B’s artistic brand of social conscience and vision.

Performances in the Studio Theatre at the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts are sold out but there is a waiting list for any last-minute openings for seats. For more information, see here.

3 thoughts on “Welcome to the union! Plan-B Theatre’s One Big Union is a Utah Enlightenment jewel”