In 1991, a very young Carlton Vickers was one of the featured musicians on a Salt Lake City performance of Composition for Four Instruments, a prescient work American composer Milton Babbitt (1916-2011) wrote in 1948 that foreshadowed the New Complexity School, one of the most significant developments in music over the last half century. Babbitt, who had won a Pulitzer Prize special citation in 1982 for his musical oeuvre, was in town for a lecture and concert, which included the work scored for flute, clarinet, violin and cello.

A Las Vegas native, Vickers was the flutist for the work, which William S. Goodfellow, then the Deseret News music critic, said was “spectacularly well realized” and “at no point was one aware that these were students.”

Apparently, Babbitt agreed, especially about the solo flute performance. “Afterward, he said it was better than the recording they did after he won the Pulitzer,” Vickers says in an interview with The Utah Review.

That experience set the tone for Vickers’ musical career, which has gained an international reputation for helping to redefine flute music in the 21st century. Internationally known composers have written works for him that create a new palette of musical expression with unprecedented technical and intellectual capabilities. The list of international composers who have written or dedicated works for Vickers – Dominik Karski, Marc Yeats, Chris Dench, James Erber and Brian Ferneyhough, for example – are among the most important composers in the 21st century for how they are advancing musical notation, the potentials of musical expression and the technical demands for instrumentalists.

For composers, it is akin to authors, poets and filmmakers who are experimenting with new narrative and freestyle forms to breach the limitations of tradition-bound genres. For performers, it is similar to how Olympic caliber athletes are busting technical barriers once believed to be insurmountable. Vickers, for example, has taken advantage of new developments in instrumental systems to handle the notational and technical challenges in the works that have been written for him. Of note has been Vickers’ use of instruments made from the patented Kingma System, a development led by Eva Kingma, a flutemaker based in The Netherlands. The Kingma line of open-hole and quarter-tone alto, bass and contrabass flutes has coincided with the body of works that is expanding the musical potential of these instruments.

Vickers is doing what many performers who stand out for their instrumental virtuosity have accomplished in the history of music. Many composers had specific soloists in mind for their concerti and chamber music works and many of these works at the time of their premieres were considered playable only by the smallest handful of musicians.

One also must acknowledge the meaning of ‘avant garde’ is unsatisfactorily posed as having ‘no rules’ or ‘no expectations.’ What was once avant garde eventually made its way to audiences: for example, the last four Beethoven string quartets and the last three symphonies of Mozart were not publicly performed until more than six decades after their composers’ respective deaths. And, it was Babbitt in 1991, as Goodfellow reported in his newspaper account of the composer’s Salt Lake City visit, who warned that “any composer today who ‘attempts to turn back the clock’ will find himself faced with a problem that did not exist a hundred years ago, namely ‘a century of sophisticated listeners whose ears will have experienced music that has forever altered their state of listening and understanding.’”

Prior to 1990, before Vickers arrived in Salt Lake City as the new flute soloist with Canyonlands New Music Ensemble (the resident group for the Maurice Abravanel Visiting Distinguished Composers Series), he had been somewhat frustrated and disappointed about new music’s ‘sick puppy’ status in the performing arts world. There were, however, some encouraging signs. For example, a Las Vegas arts council had established an artist-in-residence program to bring in composers.

Vickers recalls being hopeful in a phone conversation with Frank Zappa about a chance to perform some of his classical musical works. “However the end of the conversation ended up in being rejected by Zappa,” Vickers says. Zappa believed that his compositions were given sloppy, unpolished performances with less than thorough attention in preparation and rehearsal.

In Salt Lake City, Vickers found the Abravanel visiting composer series more conducive to the challenge of bringing new music forward. In addition to Babbitt, he worked with others who enjoyed international reputations including Sir Harrison Birtwistle, John Cage, Chen Yi, John Corigliano, Mario Davidovsky, Steven Mackey and Shulamit Ran. There also were other spots to cultivate a sustainable new music culture that developed through the end of the old millennium and the beginning of the new including the Utah Symphony, the growing emphasis on new work by organizations such as NOVA Chamber Music Series and the Salty Cricket Composers Collective as well as the New Music Ensemble at The University of Utah’s school of music and the annual composer’s commission sponsored by the Utah Arts Festival.

As Vickers explains, a more intense and intrepid culture for new music feeds those who are starving for new content that rings with authenticity and fresh energy. And, it was Babbitt’s warm appraisal of his performance on a work written 43 years earlier and which was still regarded as daring in its avant garde character that had emboldened Vickers’ resolve to perform and premiere new music as much as possible. “I realized that we could have this thriving little cottage industry – these hot houses of creativity which almost had been rejected because of the ‘eat spinach syndrome,'” a reference he makes to a parent’s insistence on consuming it for the simple yet unexplained reason of “it’s good for you.”

While Vickers continued to perform extensively in traditional classical settings as well as new music ensembles (as flute soloist for Canyonlands in Utah and and the NO EXIT New Music Ensemble in Cleveland), he gradually cultivated his musical ecosystem to include solo recitals and a growing network of contacts and collaboration with composers. He has been invited to perform at concerts and recitals on four continents, including the Dresdener Zentrum für Zeitgenössische Musik, DIEM (Danish Institute of Electroacoustic Music), SEAMUS (The Society for Electro-Acoustic Music in the United States), Third Practice Electroacoustic Music Festival and the Cleveland Contemporary Players.

Vickers’ timing in developing his niche was ideal, given other technological developments. As the Internet’s infrastructure grew with new social media platforms and communication tools, many composers not only set up websites that include audio samples of their music, some also have set up their own publishing house of scores (an important development given how many composers are more concerned with artistic control and integrity as well as experimenting with musical notation), while others have learned to leverage YouTube channels, Facebook pages, Twitter and other digital media applications.

This has generated a magnitude of word-of-mouth visibility that previously had been difficult to achieve with print media and tradition-bound music organizational management hierarchies. Many online tools have become a boon for new music distribution. For example, the capability to send a score immediately and conveniently in Adobe Acrobat PDF format via email has become one of the most strategically important tools. Skype also has been helpful for consulting composers abroad about score issues and performance notes.

At his website, Vickers offers high-quality audio and video of some of his performances. “My thrust in this project is definitely recordings,” he explains, adding that new recordings of his most recent premieres and performances are forthcoming in 2018. This is an important development, as new music rarely enjoys the realistic chance of a second listening or accessible exposure after its premiere. And, as important as streaming has become in the digital age, CDs, at least for the near future, will remain a vital piece in communicating with the music world’s gatekeepers, mainly because of the CD’s features for excellent sound quality and as documentation to be taken seriously by the media, performing arts organizations and adventurous listeners. And, despite the dismal economic fact that streaming even just one track of music only brings a fraction of a penny in revenue, the professionally produced recording still is one of the most important tools in bringing the business of new music to a wider audience.

In many instances, Vickers has emerged as the authoritative performer of choice when it comes to the flute literature written in the last four decades. One small bit of evidence emerges in the introduction on his website that includes a quote from Charles Wuorinen, one of the most prolific American composers and winner of the Pulitzer Prize in music and a MacArthur Foundation fellowship: “It takes a moment to recover from such virtuosity. Very impressive. Haven’t heard a high F like that since Sollberger.” Harvey Sollberger is an American composer and flutist who has worked closely with Wuorinen for decades so the praise is unquestionably significant.

Others have followed suit by writing music for Vickers. James Erber, a British composer, dedicated Desire Lines for solo alto flute, a work completed in 2014 in which four twenty-bar loops are repeated and subjected to between four and seven levels of varying musical activities, as he describes it. It is worth noting that composers of complex music often are expressing their own epiphanies, either with literature, art or even the complex natural forces at work in our world. In his notes for Desire Lines, Erber says that he was inspired by a pre-Baroque French painting titled An Explosion in a Cathedral by François Nomé. Erber writes that three loops are “interwoven, creating force fields, which nudge the music along parallel but differing routes,” which help create an “atmosphere of dreamy sensuality.” It is the fourth loop, the composer explains in his notes, that “fractures this easy-going coexistence,” and “constitute the most radical music in the piece.” Thus the sleepy dreamlike effects are jolted by musical sensations of “nightmarish destruction,” in the composer’s words.

In Streaming, a solo work for alto flute which the British composer Marc Yeats dedicated to Vickers at its completion in 2015, Yeats writes of the work,

Whilst Streaming is full of cross references, development and variants of its material held together by a fabric of rhythmic units permeating the work as a whole, it was conceived and should be performed as a stream of consciousness; a single, uninterrupted flow of ideas constantly in a state of flux and regeneration; detailed, colourful and frequently energetic and explosive.

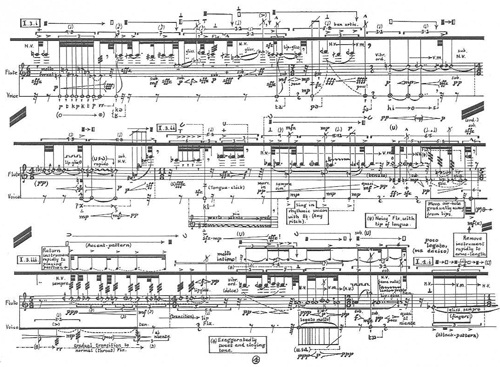

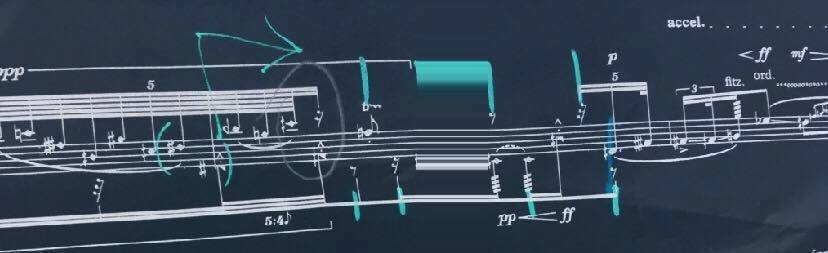

Running 22 minutes, the work is unrelenting in its demands on its performer and it typifies the intensity and energy Vickers invests in his performances. A row of music stands with scores — often in larger oversized formats that are marked in exhaustive, precise detail — stretches across the stage. Vickers, usually attired in all black, is wholly focused, often sweating because of his laser-like incisiveness as a performer. These complex compositions, which stretch the conceptual vista of musical ideas and performance, merit a dedication to the integrity and fidelity of the composer’s intentions.

There are numerous examples when composers can immediately spot a performer’s attempt to fake or dredge through a particularly complex patch of music. And, it does no justice to an audience, which is entitled to an accurate rendering of the work to find its own connection to it. Music’s complexity should never be the excuse to ignore or move on after its premiere. Vickers’ personal conscience and professional ethics as a performer are vital lessons in how new music gains legitimate ground in the musical world, especially if it can be performed or listened to more frequently.

Even the descriptions of these new works underscore their complexity and immense performing demands. One of Vickers’ most recent premieres is Geminy by Chris Dench, a British composer, who dedicated the work to Vickers and to Dench’s wife, Kathryn Sullivan, a flutist who also is researching her doctoral dissertation on the work of Edward Filmer, an English dramatist after the time of Shakespeare. As Dench notes in his score, “Carlton Vickers has exclusivity on this work lasting for two years from the date of first performance or recording. Anyone wishing to perform it while still under exclusivity should contact the composer for permission to be considered.”

Dench’s score for Geminy also is rigorously annotated with performance notes of precise detail. For example, for the work to be performed properly, the flutist must have access to the specifically designated foot-joint, which extends the range and maintains precise intonation, or otherwise the work could be performed on an instrument with an alternate foot-joint but only with the composer’s permission.

It also signifies the dynamic on complex music’s expanding landscape in the 21st century, as composers have found expert performers who can produce capably full layers of effects with articulation, playing technique, dynamics of sound and microtones and other aspects. It is a movement that has advanced since it began in the 1940s when John Cage invented the prepared piano and wrote music specifically for it. Performers, such as Vickers, go beyond the expressive powers of melody and harmony and the traditional capacities of their instruments to connect emotionally with complex music by using new tools in instrumental technique and compositional notation.

Dench noted that he conceived Geminy for alto flute because it most closely resembles the accessible capacity to switch at barely a moment’s notice between two contrasting musical discourses. One is ‘mercurial’ and substantive even it is ‘fleeting,’ in the composer’s own words, while the other is ‘furtive’ and ‘sinister ghost music.’ The effect is that both occupy the same musical space even as they alternate, not different in nature from the twin brothers Castor and Pollux, according to Dench.

Geminy will eventually become a part of Dench’s Flute Pentalogue, a set of five independent pieces with solos on various flute instruments that could be performed as one large group of compositions. That work is expected to be completed in late 2018.

The Yeats and Erber compositions were performed recently at a Dixie State University recital in the Delores Doré Eccles Fine Arts Center, along with the premieres of Dench’s Geminy and The Unquenchable for amplified alto flute solo by Dominik Karski, an Australian composer of Polish descent.

Another work that Vickers performed was Sisyphus Redux for solo alto flute completed in 2009 by Brian Ferneyhough, a composer from Britain who has been living in the U.S. for the last three decades. Ferneyhough stands out in Vickers’ long-term creative project as one of the most important creative minds in solo flute literature. His Unity Capsule, completed in 1975, may be among the best markers of Vickers’ progress as a new music presenter and interpreter. He spent more than a decade working on it before he publicly performed it and even then, he continues to finetune his interpretation of Ferneyhough’s work, even after having performed it more than 20 times. It’s not uncommon for Vickers to spend more 1,300 hours on getting a new work ready for its premiere.

Indeed, Vickers’ experience with Ferneyhough’s music accentuates the elemental thrills of new music that push the extremities of this performing arts form to thrilling new epiphanies of listening and aesthetic connection for both performers and audiences.

His performances are featured on Albany, Bridge, CRI, Capstone, Centaur, New Focus and Context Records.

Personally I dislike his pretentious unfounded alien-styled inhumane chaotic pseudo-random material, which exists only for it’s own sake and creates sensory responses that are not of the composer’s intention, but just happen to occur.

Make no mistake: Ferneyhough is no real composer; and the fact that this has never been accordingly stated or criticized shows the times in which we live: Feed the people any rubbish, with just a hint of added intellectual superiority and they’ll believe it and worship his ‘message’.

… Ferneyhough… the charlatan king of pretentious wishful implication