In 2018, speaking at a Wharton leadership conference, Kelly Martin, who was the chief of fire and aviation management at Yosemite National Park, told participants, “It doesn’t hurt for the senior executive person to take individuals aside and ask them, for instance, ‘Hey, what has it been like for you as a woman firefighter? What are some things you think we could be doing better?’” she said. She added, “you don’t have to get really heavy with people on the initial communication to really create an environment of conversation in your company.”

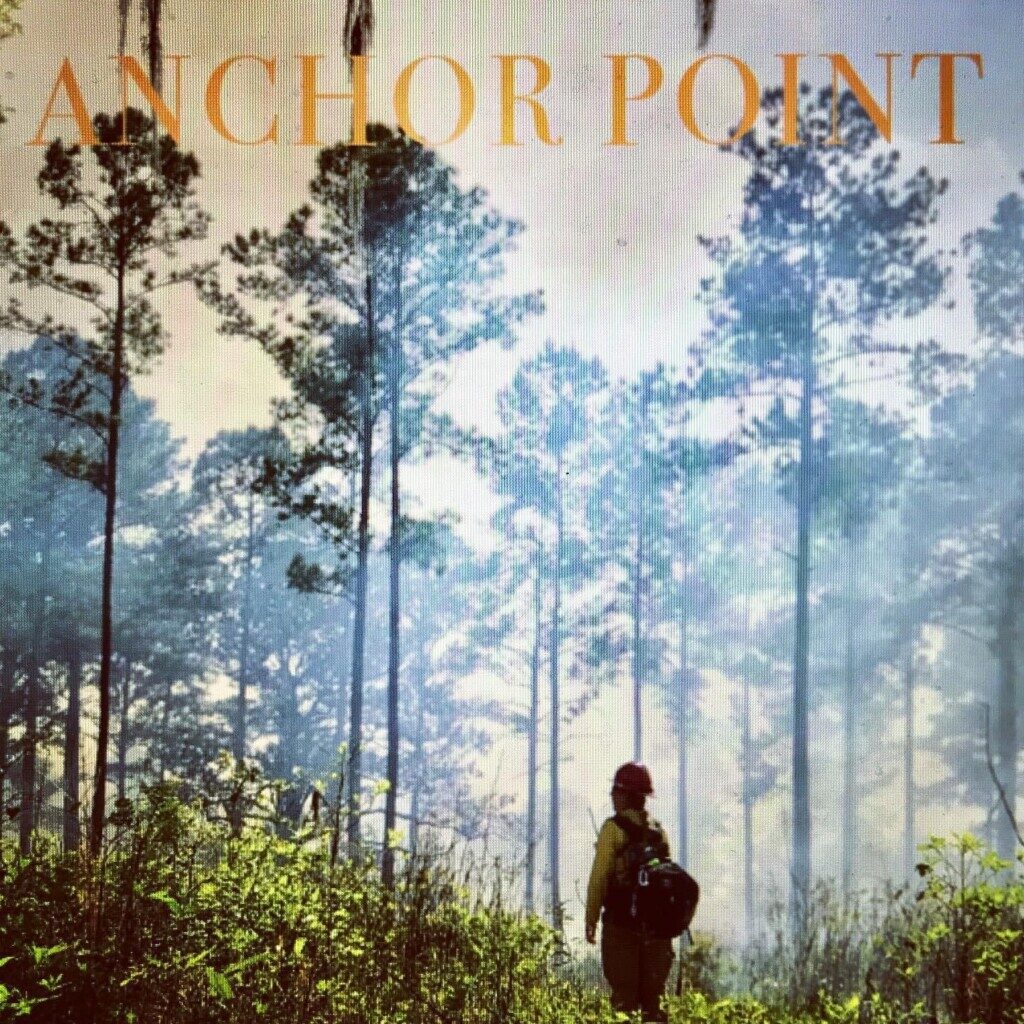

As the new documentary film Anchor Point, directed by Holly Tuckett, demonstrates splendidly in its nuanced, understated presentation, Martin weighed carefully the manner in which she approached becoming a mentor and voice of conscience to shift, enlighten and improve the working culture for professional female wildland firefighters. And, it goes well beyond rehabilitating a work environment that has been poisoned by sexual and emotional harassment. While the numbers of women are relatively small (representing just 10 percent) in the profession, their presence and contributions nevertheless highlight just how vital they can be, as firefighters confront the increasingly complicated challenges of deploying effective strategies to deal with more frequent, more intense wildfires and changing public perceptions about fire, in general.

Anchor Point will receive its premiere at the Cinequest Film Festival, which runs March 20-30, as outlined at the festival website (set to premiere at noon on March 20, along with a virtual screening party later that day at 7 p.m. MDT). The film also will receive a screening, courtesy of the American Documentary and Animation Film Festival and Film Fund (widely known as AmDocs), which helped facilitate a grant from Simple DCP for the Anchor Point production team to complete post-production services. Anchor Point is a production featuring some of Utah’s best known creative professionals, including Tuckett; producer and editor Maddy Purves and writer Jennifer Dobner along with Utah filmmakers Marissa Lila and Torben Bernhard. The film also features music by the Los Angeles-based composer Nami Melumad. The film also received a fiscal sponsorship from the Utah Film Center.

Tuckett smartly adapts the character study approach in the documentary to demonstrate how Martin and her colleagues have contended with a culture of sexual harassment, misogyny and bullying in the world of wildland firefighting. Martin values discretion and privacy, as she clearly thought about the timing to come forward to speak about what she and her colleagues have experienced. Early in her career, which eventually would span 35 years, Martin had caught a co-worker spying on her while she showered but she decided not to file a complaint. Over the years, she would discover that such incidents as well as instances of harassment and discrimination directed toward women firefighters were widespread. In 2016, as the #MeToo movement had become visible in many career fields, she prepared to testify about the experiences before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in September 2016. In 2017, Time magazine included her among The Silence Breakers in naming The Person of the Year.

Tuckett also offers the story of Lacey England, a generation younger than Martin, who like her mentor, has seen how women are so quickly disparaged by men, who believe they are incapable of dealing with the strenuous physical demands of their work. Yet England, like her female colleagues, prove that they meet the same demands in training and certification, such as rappelling to the ground. England also sees potential in diversifying the perspective of knowledge in her field. Indeed, wildland firefighters recently have seen extended seasons of wildfires that have become more aggressive but there also are questions about fire suppression and tactical strategies, of which many were based on outdated knowledge that has little relevance to today’s conditions. And, England, like Martin, see the importance of not demonizing fire as always being bad, taking a cue, for example, from the Indigenous knowledge about fire culture. In fact, many scenes in Anchor Point present fire in symbolic and miss-en-scène ways, which clarify the epiphanies to be taken from the film.

Tuckett also features scenes from the Women-in-Fire Training Exchange (WTREX) program, which Martin coordinated to provide a path for a new generation of leaders in the profession. Not only do participants come from the U.S. but also from Canada, Australia and Portugal and some 10 percent of the participants are men. The impact of WTREX is significant, especially for women firefighters who come from teams where they might be the only female or among just a handful. More broadly, firefighters, men and women, also must deal with issues of what to do during the off-season as well as the emotional challenges that come with their work, manifested variously through isolation, suicide, trauma and substance abuse. There also is the expanded base of knowledge about fire, driven by numerous practical, social, scientific, and cultural considerations that have enhanced relevance to many wildfires that have become major news events in recent years.

With the final edited version of the film, viewers will be impressed by the straightforward yet understated candor of the women. However, as Tuckett explains in an interview with The Utah Review, earning the trust of the documentary subjects did not occur automatically. One, Martin and England did not want their stories to be sensationalized. “We talked about this at length because they did not want a ‘trauma porn’ piece,” Tuckett says. ”When Lacey [England] went to a Sundance screening last year of Ron Howard’s Paradise [a film about the deadly wildfire in 2018 that devastated the eponymous California town], she said it was a lot of trauma porn that also focused too much on portraying fire as the villain.”

The clincher to proceed with Anchor Point filming came in a humorous incident in Tallahassee when Tuckett and the production principals arrived after a red-eye flight and had managed just a couple of hours of sleep prior to meeting Martin, England, and other women firefighters to talk about how the film would be made. “We were going to wing it but we also wanted them to tell us what they wanted the story to be,” she recalls. Prior to the trip, Tuckett and her team were advised to arrive at the meeting “fire ready,” which meant having fire boots and cotton undergarments. As Tuckett had noted in a blog, “In wildland fire, cotton or wool underwear is the rule; the fabrics hold up in the extreme temperatures of a fire and won’t melt and stick to the skin.”

That small detail was important. The firefighters had been skeptical of journalists and other filmmakers with whom they met because they were concerned that they would be portrayed as victims. England, for example, functioned as the main public relations contact for the group and the film portrays how the women firefighters had thought long about articulating their concerns and messages in telling their stories. Returning to the Tallahassee meeting, “I was nervous because the mood in the room was icy and quiet,” Tuckett explains. “When I asked if there were any questions, somebody yelled out, ‘Did you bring cotton panties?’ I dropped my pants to show them that, in fact, I had. Kelly [Martin] came up and said I was hilarious. She said, ‘That took guts and you’re going to fit in.’ I was willing to be vulnerable.”

Likewise, in the aftermath of the 2016 Congressional hearings, Martin generally avoided one-on-one interviews but she welcomed Tuckett and the production crew to Yosemite to continue the conversation. Even in the film’s final scene located on Martin’s property in Idaho, which was shot during the pandemic unlike the other footage seen in the documentary, Tuckett agreed to her wishes not to show her home. However, Martin did agree to a scene being shot in her kitchen and some footage outside in the drive with her and England. The final scene was shot exclusively by Tuckett.

An intelligent, personable, astutely framed film, Anchor Point arrives at a serendipitous moment. With Deb Haaland as the nation’s first Native American cabinet secretary serving in the U.S. Department of Interior and a new federal administration that appears to encourage precisely the diverse, enlightened dialogue to reform and improve the broader culture involved, it appears that the hopes of Martin, England and colleagues could be transformed into meaningful actions and policies.

This is Tuckett’s second feature-length documentary film. Her first, Church & State, received its debut in 2018, winning a Special Jury Award at AmDocs and Best Feature Documentary at the Nice International Film Festival in France. For more information about Anchor Point, see the film’s website.