After being closed for five and a half months, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) at The University of Utah will reopen to the public on Wednesday, Aug. 26.

The museum will be open for three days each week, Wednesdays through Fridays, noon to 5 p.m. Seniors and high-risk visitors are invited to visit on these days between 11 a.m. and noon. The capacity of visitors will be limited to 100 at a time. Groups of up to 10 people will be admitted. Touch points have been minimized, cleaning protocols are enhanced, and the building’s HVAC system has been assessed by university facilities experts to ensure that they exceed U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines.

Visitors and staff will be required to wear face coverings and maintain the recommended social distance of six feet between themselves and other visitors or household groups, in accordance with the university’s COVID-19 policy. Visitors are strongly encouraged to reserve tickets in advance at the UMFA website. Tickets may also be purchased at the welcome desk upon arrival—but to guarantee entry, advanced tickets are recommended. The museum store will be open along with the café, which will provide beverage service only.

Galleries will be open including three exhibitions – one that opened last November and two that opened last winter, which are featured below. While group tours and classroom visits are on pause, the UMFA will offer digital resources and tours, as well as new distance learning opportunities and digital classroom visits for K–12 educators and university professors. All UMFA events and programs, including Third Saturday for Families, will be held online until further notice.

The Utah Review highlights three exhibitions of major interest:

Utah Women Working for Better Days!

The Utah Women Working for Better Days! exhibition, presented in the museum’s ACME lab, had opened in early March, just one week before the museum closed for the pandemic. Coordinated with Better Days 2020, a local organization dedicated to building visibility of women’s history in Utah, the exhibition is a marvelous sampler of social and political activism underlying three important anniversaries marking women’s voting rights: the 150th anniversary of Utah as the first place where women had the right of enfranchisement in the U.S.; the 100th anniversary of the enactment of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and the 55th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, which banned race-based discriminating in enfranchisement laws. Notably, the exhibition also highlights the value and challenge of encompassing the full spectrum of women’s history, not just limited to figures associated with Mormon pioneer days. The depth of diversity will surprise and inspire visitors to explore these implications more extensively.

The exhibition, which will remain open through Dec. 6, is wisely pointed toward the value of leveraging this historical legacy for current political stakes in the forthcoming elections. Along with materials curated from the University Marriott Library’s Special Collections, the exhibition features some illustrations, created by Brooke Smart and commissioned by Better Days 2020,which introduce visitors to major figures in the state’s history of women. They include Seraph Young Ford, the first woman in the U.S. to vote under an equal suffrage law; Mae Timbimboo Parry, master storyteller and matriarch of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation; Alice Kasai, advocate for Japanese Americans’ rights and international peace; Reva Beck Bosone, Utah’s first female judge and first U.S. congresswoman from Utah; Ivy Baker Priest, first woman to be U.S. Treasurer; Emmeline B. Wells, Utah’s leading suffragist and editor of the Woman’s Exponent, and Elizabeth Taylor, journalist, editor and president of the Western Federation of Colored Women. Others include Olene Walker, Utah’s first (and only) female lieutenant governor and governor; Ellen “Mama” Selu, community leader and host of KRCL’s Voice of Polynesia radio show, and Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon, first female state senator and founder of the Utah State Board of Health. Better Days 2020 also has compiled short biographies of all 50 women represented in the illustrations, which can be accessed at the organization’s website.

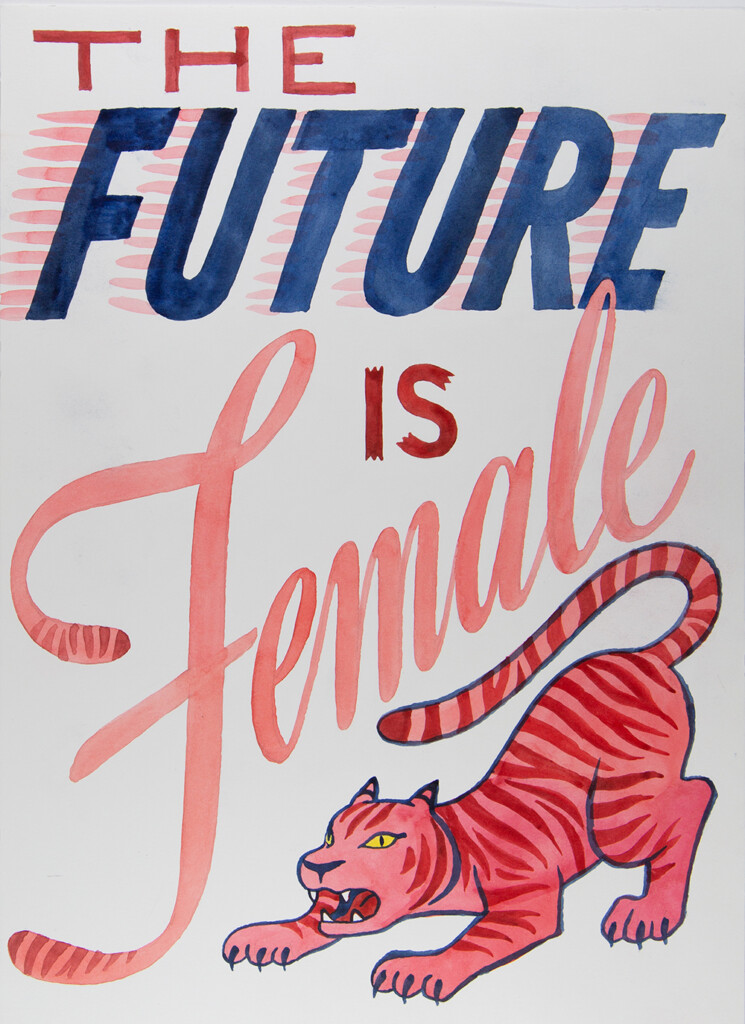

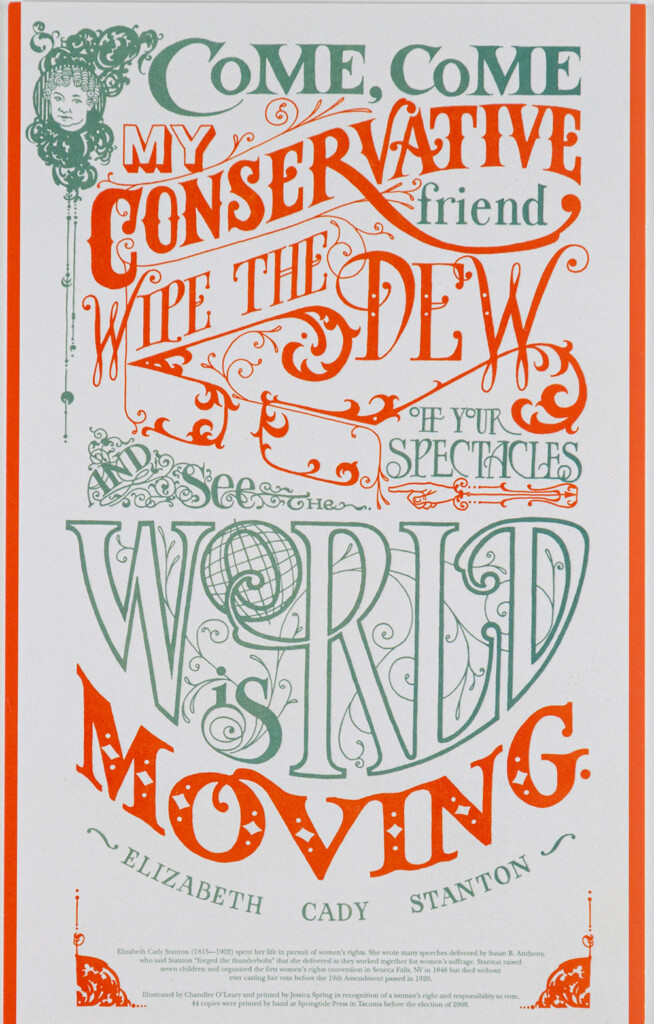

The compact nature of the exhibition, nevertheless, offers a multitude of items documenting a complex history. There are examples of newspapers, newsletters, suffrage songbooks, protest banners, correspondence and campaign literature along with some interactive elements including audio of suffrage songs and a KUED-TV clip of major Utah women historical figures. Activism is a timeless art and the images illustrate the remarkable continuity of the practice in the roughly 150 years encompassed by the exhibition. These include a 1915 photo of Utah suffragists who marched on downtown Salt Lake City’s Main Street to meet U.S. Senator Reed Smoot outside Hotel Utah and persuade him to support the constitutional efforts for suffrage. There also are items representing the Women’s March in Washington from 2017. Visitors will see items, for example, with Girl Power; Come, come, my conservative friend; The Future Is Female. Likewise, hats and sashes also have been a staple of women’s activism.

One significant takeaway from the exhibition is how enfranchisement did not occur on a wholesale basis, as noted in the anniversaries celebrating 1870 and 1920, respectively. And, of course, Utah disenfranchised women as a condition for outlawing polygamy, necessitated by the U.S. Congress’ demands for the state to qualify for admission to the Union.

UMFA’s exhibitions in recent years have succeeded in capturing a breadth and depth of sociological perspective. And, this latest example is assured by the collaborative team responsible for this exhibition, coming from UMFA staff, J. Willard Marriott Library Special Collections and Better Days 2020, including that organization’s historical director (Katherine Kitterman) and education director (Naomi Watkins).

“We loved the idea from our first meeting about the collaboration,” Kitterman says, adding that it was an excellent way to showcase how women’s activism did not evolve uniformly as a monolith. Ironically, the delays in reopening the museum have magnified the exhibition’s potential impact as interest in the forthcoming elections will reach its pinnacle in the next 70 days.

There are some surprising discoveries, which emphasize why some footnotes must be lifted from the margins and placed prominently in the main text of the history of Utah women. Among the most significant is The Utah Plain Dealer, a newspaper from the early 20th century owned and operated by Utah women of color, most notably Elizabeth Taylor. The Utah Plain Dealer was one of six black newspapers in Utah representing minority voices between 1890 and 1910. So difficult was the challenge of finding exhibition-suitable images from the library’s archival collections but then organizers came across a reproduction of a July 2, 1904 Plain Dealer front page in the papers of Ronald Coleman highlighting Leading Black Women of the Federation Movement.

“We were excited to find this story, along with the portraits of the women who participated in the movement,” Alana Wolf, collections research curator, wrote in a blog. “Although it was only a fragment of a photocopy of the paper, it introduced us to a group of women clearly at the forefront of making change in their communities.” It is heartening to see the juxtaposition of familiar groups in the exhibition such as the League of Women Voters with other lesser known entities, including the aforementioned publications along with pamphlet materials from the ERA Missionary Project to reach Mormon women during the 1970s and 1980s.

As Jessica Breiman, art and archives metadata librarian from the Marriott staff, noted in a blog, deciding what to include in such a compact exhibition was difficult, starting from 300 objects and narrowing it to 19. Archival collections require a great deal of time and focus.

“Though we grapple with the question of what should be collected and by whom, it is clear that further research is imperative to better identify and represent ‘missing’ voices,” Breiman explains, “and that firsthand accounts of contemporary activists and records of community organizations that represent the diversity and heterogeneity of Utah must be preserved.” Indeed, examples such as notes that Bosone took on her opponent’s (Priest) campaign brochure for a 1950 Congressional illustrate just how complex women’s political activism could be.

In tandem with the exhibition, a special edition of KRCL’s Radioactive show, produced by Lara Jones and hosted by Giuliana Serena of The Bee, will air Oct. 6 at 6 p.m. The edition titled Because of Her: Stories of Women Making a Difference will feature storytellers including activist and teacher Erika George; Luna Banuri, executive director of the Utah Muslim Civic League; Ciriac Alvarez Valle, poet and community organizer; artist Pilar Pobil, and Denae Shanidiin, creator, Bilá’ashdla (five-fingered relative) and Honágháahnii (one who walks around clan).

Beyond the Divide: Merchant, Artist, Samurai in Edo Japan

In February, UMFA opened its largest presentation of Japanese art in its history, featuring twin exhibitions. Unfortunately, one of the shows was a limited run and could not be extended for the museum’s reopening: Seven Masters: 20th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints, a show organized by the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) with its tour made possible by International Arts and Artists in Washington, D.C.

However, the remaining show is exceptional in its own regard and its dates have been extended for viewing: Beyond the Divide: Merchant, Artist, Samurai in Edo Japan, an exhibition of Japanese scrolls, screens, sculpture, prints and samurai armor and weapons from the museum’s own collection. Curated by Luke Kelly, UMFA’s associate curator of collections and antiquities, this exhibition presents works not seen by the public in more than a decade. These items had been stored prior to the museum’s major renovations, which were completed several years ago.

As noted last February in The Utah Review, the Beyond the Divide exhibition is an unusually good anchor for appreciating the historical roots that led to the rise of the shin hanga movement in the Seven Masters exhibition. Kelly situates the cultural apotheosis of the Edo period (1603 – 1868) as it evolved through the highest aims of the samurai class in balancing exquisitely the tools associated with warfare and cultural enlightenment and later with the rise of a merchant class that sought its own place in society as patrons of the arts. And, in the middle, were the artists and artisans, who rose in status, especially as they developed their creative identities along the realms of established schools and studios which had defined Edo-period culture.

It is an eclectic show of impressive proportions. An outstanding jizai okimono (object of art) is a 19th century steel and silver sculpture of an articulated raptor, set on a perch, with incredible detail in its carved feather and its movable parts.

Another is a pristinely preserved sword with mountings and scabbard (katanakoshirae with saya) and its lacquered wood sheath. The sword from the early Edo period is attributed to Yamato no Daijō Fujiwara Masanori (active 1661–1673) and is mesmerizing in its phenomenal craftsmanship: the sword blade (katana) has its full mounting (koshirae), including handle, sword guard (tsuba), and scabbard. Kelly says while these weapons definitely were made for warfare, a samurai also selected decorative sword mountings with equal care to reflect their persona.

Katana swordplay has enjoyed a resurgence in Japan, especially among young women who have adapted ancient sword fighting skills into physical exercise, as developed by Ukon Takafuji, successor chief of the Takafuji-ryu school of Japanese classical dance.

From a later period, either in the 18th or 19th centuries, a full set of samurai armor is on display, made from steel and iron along with silk, leather, wood hemp and lacquer. It also is an early version of a bulletproof vest, with circular dents that would have withstood the impact of musket weapons that were introduced during the Edo period.

The exhibition presents numerous prints from masters of the traditional ukiyo-e form: Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), among the most widely known of the traditional ukiyo-e artists.

The screens deserve more than a cursory glimpse because of the breadth and depth of detail. From the mid-19th century, Kaiho Yusho II (1818-1869) created scenes from the 11th century Tale of Genji, a fictional story about a prince written by Murasaki Shikibu, a Japanese noblewoman and the source of numerous artistic representations. As one scans the scenes from the right toward the left screen, the prince’s life story easily can be followed from his early years.

As noted last February, Kelly says that each time he views the screens, he discovers something new. “There are so many details within the details,” he adds.

Another captures the astounding formal techniques of the Edo period in the early 18th century – The Four Accomplishments by Kano Tsunenobu (1636–1713). Besides their artistic magnificence, the extensive use of gold leaf served the function of providing more light in a room with the folding screens (byobu). There are countless details on the screens, which stand seven feet tall and measure 144 inches across, each rendered with painstaking exactitude.

Again going from right to left, there are miscellaneous scenes featuring music, calligraphy, painting and a whimsical scene with the game of go (Chinese chess). This is notable because the daimyo lords and samurai followed the “four accomplishments,” as articulated in Confucian philosophy, and incorporated these Chinese principles into their training for the arts of war (bu) and culture (bun). This became a central tenet in the Edo-period’s pedagogy for Japan’s highest family class.

Loans from Smithsonian American Art Museum, Art Bridges

Given that UMFA had the option to select work from more than 7,000 artists who are represented in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) collection, the final choices that can be viewed in the museum’s permanent collection galleries until Oct. 4 are spectacular for two reasons. As noted last November in The Utah Review when this special exhibition opened, first, the three works, one each by Thomas Moran (1837-1926), Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) and Alma Thomas (1891-1978), dovetail well with UMFA’s artistic mission and cultural imprint in the community. Second, the works exemplify the artists at critical junctures in their creative development, as an additional unifying theme.

The bonus is a fourth work, also on loan, as made possible from the collection of Art Bridges: a 1931 painting by Diego Rivera (1886-1957).

UMFA was one of five institutions in the U.S. West that SAAM selected for an unprecedented five-year collaboration known as the American West Consortium, supported by a nearly $2 million dollar grant from Art Bridges and the Terra Foundation for American Art. In an interview with The Utah Review last October, SAAM’s executive director Stephanie Stebich says the institutions were selected from a pool of a dozen candidates. The intention was to select four but the finalists were so strong that SAAM decided to expand the group by one, she adds. “Needless to say, as an institution of art, the UMFA is the flagship of the university, the city and the state and it is very much at the top of its game in arts education and pioneering programs,” Stebich explains, citing the vision of Gretchen Dietrich, UMFA’s executive director.

One of the works is Thomas Moran’s Mist in Kanab Canyon, Utah (1892), one that Stebich says, “definitely had to be in Utah.” The opportunity to exhibit this archetypal landscape painting that will resonate with local visitors is serendipitous. This painting is placed with other works in the outstanding permanent exhibition American and Regional Art: Mythmaking & Truth-Telling. The one Moran work that already is in the permanent collection is a watercolor on paper – the Great Blue Spring of the Lower Geyser Basin, Firehole River, Yellowstone (1872).

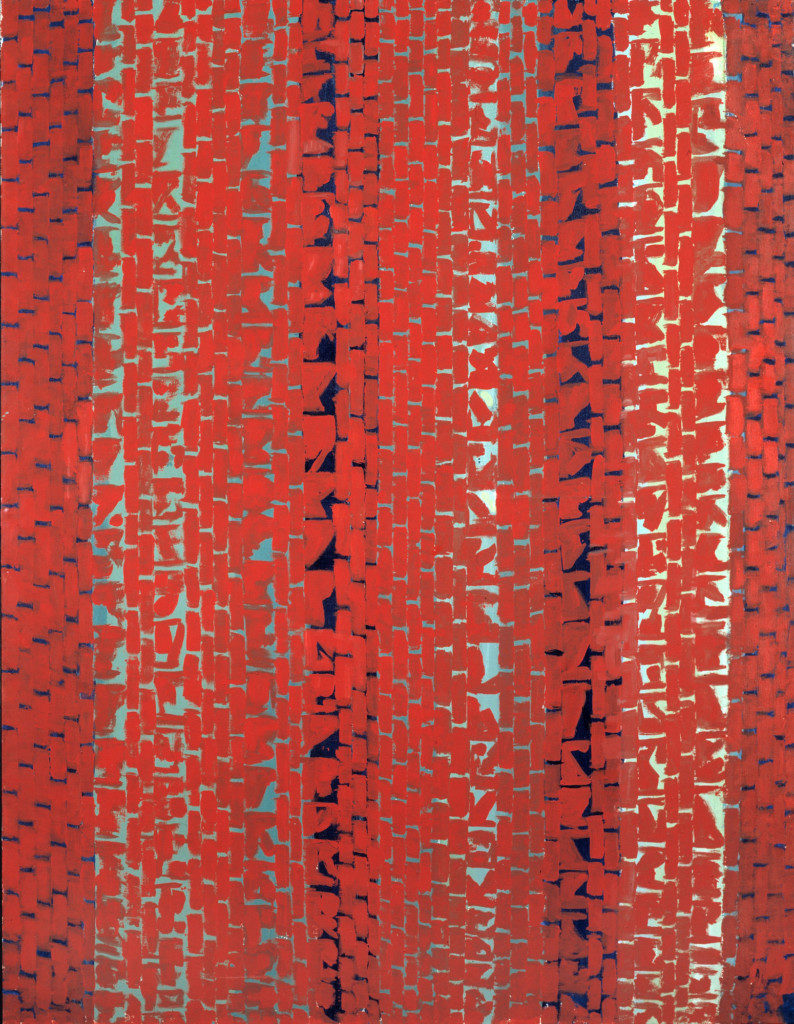

The second is a pure stunner: Alma Thomas’s Red Sunset, Old Pond Concerto (1972). It is placed in gallery space devoted to the Washington Color School representing Art Post-1945, the UMFA’s exhibition of its modern and contemporary collection. Thomas’ active career as a professional painter barely spans the last two decades of her life. This 1972 work signifies her mature grasp of dealing with as few colors as possible and achieving an abstract effect with optical elements, as Sachi Yanari-Rizzo, a curator at the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, explains. In a 1973 interview, Thomas explained, “I now paint blocks that are looser … floating hither and yonder, some straight, others curved in monochromatic color on single color background or several colored background, making the canvas an integral part of the picture.”

The Red Sunset, Old Pond Concerto painting evokes a warm impressionistic sensation of musicality. Meanwhile, across the gallery aisle, there is an appropriate Washington Color School counterpoint – Gene Davis’ Jasmine Sidewinder #91 (1969), which pops with jazz sensibilities. This Davis work is part of UMFA’s permanent collection.

Securing the loan of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Manhattan (1932) was a major coup for UMFA. Stebich says it is among the most requested works for exhibition loans. At the UMFA, it is placed in a stupendous setting in the American and regional art gallery focused on modernism. For decades, many thought Manhattan was lost or destroyed but after O’Keeffe’s death at the age of 98, it was discovered in her private collection. It is the most in-your-face rendering of the Big Apple’s unique skyscraper scene with the curious appearance of blossoms free floating in the world’s most urbanized setting.

Close by in the same gallery space as the O’Keeffe work is the Art Bridges loan, Rivera’s La ofrenda (1931), which depicts the altar and ritual associated with Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Rivera’s connection to MOMA was significant at the time, as he was only the second artist to be honored with a one-person show. This work came amidst a larger effort in which Rivera was creating art to illustrate Popol Vuh, a mythological and cosmological text representing a group of Mayan indigenous people who thrived in the Guatemalan highlands before the Spanish conquered the country. Despite the pre-Hispanic mythological inspiration, Rivera expands the geographical orientation into a contemporary spirited expression that is pure cosmic joy.

Viewers in this particular gallery should absorb the other works that are anchored by the presence of the O’Keeffe and Rivera paintings. These include extraordinary gems by American abstract artists including Charles Biderman (1906-2004) and Charles Green Shaw (1892-1974) along with John Storrs (1885-1956), an American modernist sculptor who captured Art Deco style in unique expressions. Also on display is a preparatory study by Maynard Dixon (1875-1946) that would become part of the magnificent The Pageant of Tradition mural in the California State Library. Dixon, mostly self taught, is considered one of the greatest American West artists, especially for his interpretation of Native American themes. Likewise, Battle of the Bulls by Minerva Teichert (1888-1976) and Hopi Women by Laura Adams Armer (1874-1963) deepen the remarkable context realized by viewing the Rivera painting.