“They chose well,” Stephanie Stebich, executive director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), says, in an interview with The Utah Review, of the paintings the Utah Museum of Fine Arts staff chose as loans made possible by two innovative programs established to share works from the nation’s most prestigious art collections.

Given that UMFA had the option to select work from more than 7,000 artists who are represented in the Smithsonian collection, the final choices that now can be viewed in the museum’s permanent collection galleries until Oct. 4, 2020 are spectacular for two reasons. First, the three works, one each by Thomas Moran (1837-1926), Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) and Alma Thomas (1891-1978), dovetail well with UMFA’s artistic mission and cultural imprint in the community. Second, the works exemplify the artists at critical junctures in their creative development, as an additional unifying theme.

The bonus is a fourth work, also on loan, as made possible from the collection of Art Bridges. This is a 1931 painting by Diego Rivera (1886-1957), which also has inspired a year-long partnership with Artes de México en Utah, a local nonprofit that promotes the appreciation of Mexican art.

UMFA was one of five institutions in the U.S. West that SAAM selected for an unprecedented five-year collaboration known as the American West Consortium, supported by a nearly $2 million dollar grant from Art Bridges and the Terra Foundation for American Art. The other institutions are Boise Art Museum, the Jordan Schnitzer Museum (Eugene, Oregon); the Nevada Museum of Art and the Whatcom Museum (Bellingham, Washington). The partnership comprises a two-part exhibition program and professional exchange sessions. The first phase encompassing loans from the SAAM collection is underway at all five institutions. A second phase will feature an exhibition curated collectively by all five institutions. That exhibition will include works from the participating museums. UMFA will be the last stop for that exhibition in 2023, before it is presented at SAAM in Washington, D.C. as the final stop.

Stebich says the institutions were selected from a pool of a dozen candidates. The intention was to select four but the finalists were so strong that SAAM decided to expand the group by one, she adds. “Needless to say, as an institution of art, the UMFA is the flagship of the university, the city and the state and it is very much at the top of its game in arts education and pioneering programs,” Stebich explains, citing the vision of Gretchen Dietrich, UMFA’s executive director.

One of the works is Thomas Moran’s Mist in Kanab Canyon, Utah (1892), one that Stebich says, “definitely had to be in Utah.” The opportunity to exhibit this archetypal landscape painting that will resonate with local visitors is serendipitous. This painting is placed with other works in the outstanding permanent exhibition American and Regional Art: Mythmaking & Truth-Telling. The one Moran work that already is in the permanent collection is a watercolor on paper – the Great Blue Spring of the Lower Geyser Basin, Firehole River, Yellowstone (1872).

Moran’s Kanab landscape is full of intriguing context. As with many American artists in the late 19th century, Moran visited Venice and its appeal influenced his work. “The streets, the squares, the gardens, and the buildings were all bathed in a sun-drenched glow which was caused by the reflections of light from both the sun above and sun’s reflections in the water of the canals,” as noted by Saralie Martin-Neal from a 1977 study of Moran in context with other artists who also were known for their work depicting the Grand Canyon. Moran moved away from watercolor studies and began to repaint older works, including the Mist in Kanab Canyon painting, which was completed in 1892. It is a breathtaking work for its ethereal radiance.

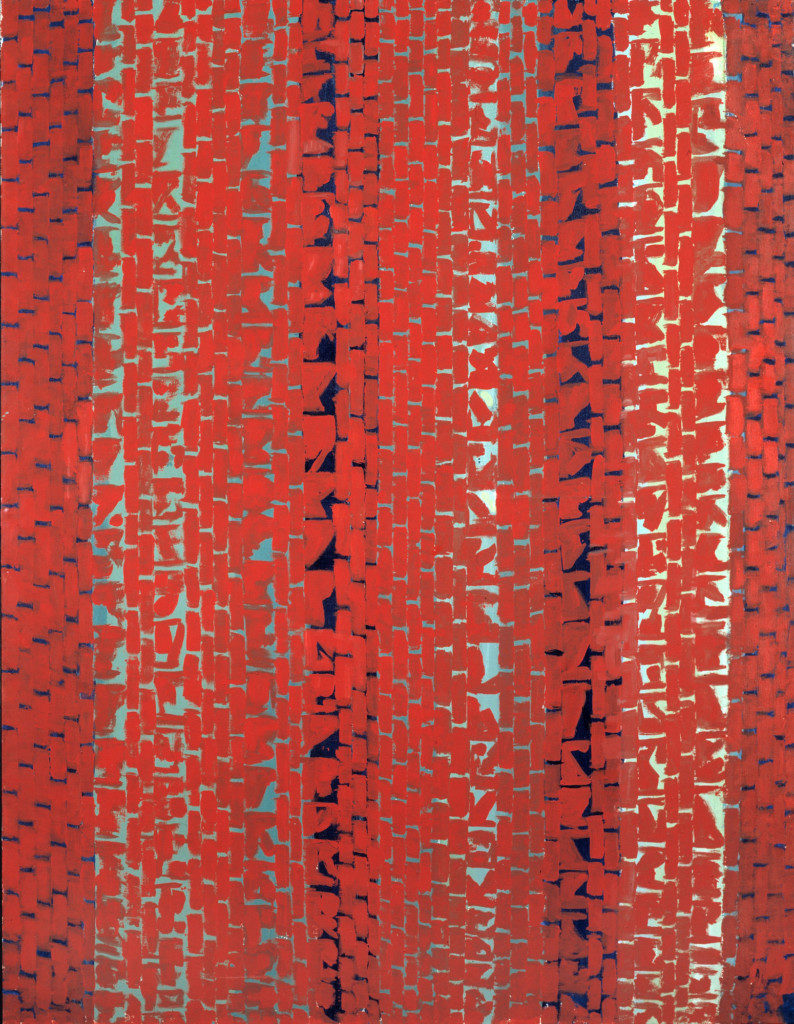

The second is a pure stunner: Alma Thomas’s Red Sunset, Old Pond Concerto (1972). It is placed in gallery space devoted to the Washington Color School representing Art Post-1945, the UMFA’s exhibition of its modern and contemporary collection.

Thomas’ active career as a professional painter barely spans the last two decades of her life. In 1957, already past the age of 65, she studied with Jacob Kainen at American University in Washington, D.C., in the hopes of “modernizing” her technique and style. In fact, it was Thomas’ quick rise as an exceptionally skilled colorist that influenced Kainen’s later approach, especially after he retired from the Smithsonian in 1970.

The more Thomas experimented, the accolades, exhibitions and visibility intensified. This trend continued into her eighties, the last phase of an extraordinary life. She was featured in major articles in newspapers and magazines, most significantly in a December 1975 profile in Black Enterprise. Thomas, a Howard University alumna who always had art and creative endeavors near her side throughout her life and career, resisted being judged by the color of her skin.

This 1972 work signifies her mature grasp of dealing with as few colors as possible and achieving an abstract effect with optical elements, as Sachi Yanari-Rizzo, a curator at the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, explains. In a 1973 interview, Thomas explained, “I now paint blocks that are looser … floating hither and yonder, some straight, others curved in monochromatic color on single color background or several colored background, making the canvas an integral part of the picture.”

The Red Sunset, Old Pond Concerto painting evokes a warm impressionistic sensation of musicality. Meanwhile, across the gallery aisle, there is an appropriate Washington Color School counterpoint – Gene Davis’ Jasmine Sidewinder #91 (1969), which pops with jazz sensibilities. This Davis work is part of UMFA’s permanent collection.

Securing the loan of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Manhattan (1932) was a major coup for UMFA. Stebich says it is among the most requested works for exhibition loans. At the UMFA, it is placed in a stupendous setting in the American and regional art gallery focused on modernism.

For decades, many thought Manhattan was lost or destroyed but after O’Keeffe’s death at the age of 98, it was discovered in her private collection. It is the most in-your-face rendering of the Big Apple’s unique skyscraper scene with the curious appearance of blossoms free floating in the world’s most urbanized setting.

The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) had commissioned 65 artists to create wall-sized decorations for a 1932 exhibition. They had just six weeks to prepare submissions of a mural mockup measuring 20 inches by 48 inches. O’Keeffe came up with a triptych of cityscapes, and eventually the middle one was rendered completely as a painting. It was that success which led to the newly opened Rockefeller Center to commission a mural from her but because of various problems, including O’Keeffe’s desire to compose the mural entirely of flowers, it ultimately went to another artist (Yasuo Kuniyoshi).

Manhattan is a striking diversion from the work by which O’Keeffe is best known for in the American West. It is at least double the size of other cityscapes she rendered. “Pitting pink against red, mauve against blue, black against white, the painting offers up a jazz-age brashness and surface tempo we seldom see in her work,” Wanda Corn wrote for a 2006 issue of American Art. “O’Keeffe also infused the piece with cubist and futurist rhetoric, two vocabularies she rarely engaged as methodically as she does here.”

Close by in the same gallery space as the O’Keeffe work is the Art Bridges loan, Rivera’s La ofrenda (1931), which depicts the altar and ritual associated with Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Rivera’s connection to MOMA was significant at the time, as he was only the second artist to be honored with a one-person show.

This work came amidst a larger effort in which Rivera was creating art to illustrate Popol Vuh, a mythological and cosmological text representing a group of Mayan indigenous people who thrived in the Guatemalan highlands before the Spanish conquered the country. Despite the pre-Hispanic mythological inspiration, Rivera expands the geographical orientation into a contemporary spirited expression that is pure cosmic joy.

Viewers in this particular gallery should absorb the other works that are anchored by the presence of the O’Keeffe and Rivera paintings. These include extraordinary gems by American abstract artists including Charles Biderman (1906-2004) and Charles Green Shaw (1892-1974) along with John Storrs (1885-1956), an American modernist sculptor who captured Art Deco style in unique expressions. Also on display is a preparatory study by Maynard Dixon (875-1946) that would become part of the magnificent The Pageant of Tradition mural in the California State Library. Dixon, mostly self taught, is considered one of the greatest American West artists, especially for his interpretation of Native American themes. Likewise, Battle of the Bulls by Minerva Teichert (1888-1976) and Hopi Women by Laura Adams Armer (1874-1963) deepen the remarkable context realized by viewing the Rivera painting.

Throughout the forthcoming year, UMFA also will present several programs associated with this exhibition. They include a free, public lecture by Anna Indych- López, an expert on Rivera (March 21, 2020), sponsored by Art Bridges. The free, public art-making sessions as part of the museum’s Third Saturdays for Families program will include printing holiday cards (Nov. 16, 1 p.m.- 4 p.m.) and landscapes and cityscapes (May 16, 2020, 1 p.m. – 4 p.m.).

At the Marmalade branch of the Salt Lake City Public Library, on Nov. 21 (6:30 p.m.), a free, public session as part of the museum’s ACME program will be offered. It is inspired by Innovando la Tradicion (Innovating Tradition), a multidisciplinary non-profit and sustainable design project in Oaxaca, Mexico, where artisans, designers and artists share skills, knowledge and stories to rethink and honor ceramic traditions. They offer services to potters and pottery communities in Oaxaca that support the development of their trade.

For more information, see the Utah Museum of Fine Arts website.