Three new exhibitions at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) are striking examples of self-referential autonomy in the visual arts, as presented by Utah artists Annelise Duque, Yujin Kang and Jorge Rojas. These exhibitions are open through July 31. For more information see the UMOCA website.

Jorge Rojas: Corn Mandala: Flower of Life

In preparing to install the largest corn mandala of his career to date, Jorge Rojas engaged in a ritual of fasting, meditation and prayer. He burned incense made from Mexican resin, a substance of sacred significance to the Maya and Aztec civilizations. His personal meditative care was crucial to the eye for detail needed in installing a mandala on a 10-foot by 10-foot platform in the Projects Gallery of the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA).

Flower of Life is Rojas’s fifth mandala and the second created for UMOCA. When Jared Steffensen, UMOCA’s curator, asked Rojas, a Utah artist whose native roots are Mexican and Indigenous, about exhibiting work in the gallery space, he immediately locked onto the artist’s interest in creating a corn mandala.

A stunning visual masterpiece of the utmost handcrafting, the mandala’s symbolism emanates throughout the sparse installation space. “During the pandemic, there were so few ways of expressing public empathy and no opportunity for people to get together to mourn those who were lost to the disease,” Rojas says. “It symbolizes life, healing and the renewal of life and love.”

Rojas is driven by the sacred geometry that leads to the ancient symbol of the Flower of Life. It is perhaps the purest icon shared among all ancient civilizations and faiths, rendered by each in their own unique expression. Made entirely of corn kernels placed by hand, the mandala epitomizes an extraordinary exercise of patience. Taking two full days to install the mandala, Rojas and his two children were joined by Steffensen and his assistant. Up to an estimated 200 pounds of seeds were used.

While Rojas encourages visitors to come up with their own readings of the piece, the mandala signifies for him the wholeness of his ancestral, familial and cultural roots. Among his inspirations is the 1949 novel Hombres de Maíz by Miguel Ángel Asturias, the Guatemalan writer who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1967. The novel is principally allegorical but it also is crafted from the legends of the Kʼiche’, one of the Maya peoples, who inhabit the Guatemalan Highlands, along with the Popol Vuh, the central Mayan sacred text. It is centered around the belief that the people’s flesh was made from corn.

As Aleksín H. Ortega explains, Asturias succeeded first at redirecting the reader from a mindset based on Western culture to one rooted in the Indigenous world and then subsequently the parallel constructs “to establish a connection between Mesoamerican mythology and the primitive conceptions of the world recorded in Europe and elsewhere.” Sacrifice is the unifying point upon which Asturias builds the stories in his novel. Ortega adds that this allows the reader to “enter a mythological journey towards the Mayan-Kʼicheʼ worldview. Through this method Asturias manages to demonstrate the validity of this worldview.”

Rojas was born in Mexico and at the age of six, his mother brought him to the U.S. along with his siblings but they also moved back and forth between both countries. He grew up in Provo and went to art school in Mexico. Rojas, who recently left his position at the Utah Museum of Fine Art to devote more time to his projects, went to art school in Mexico and would bounce around between Salt Lake City, New York City and Seattle. “So, I always have had this sense of belonging and not belonging,” Rojas explains. “As a person who has existed in both countries with a perspective on the respective cultures as an outsider who does not necessarily belong in one or the other, I learned to appreciate this sense by developing a critical eye to both.”

As Rojas developed his artistic language, he was invited to participate 10 years ago in Project Row House in Houston, which he describes as an “amazing place case study utilizing art to deal with issues of gentrification and artists and their role in the community.” At the time, Rojas already had developed a performance persona as the Tortilla Oracle, which arose from more than three decades of reading tarot cards. For the Houston artistic residency, Rojas was asked to augment his performance with a row house project that dove into the history of corn. Again, inspired by the Asturias novel, Rojas made a corn mandala but also set the stage to create people of corn, made with masa maseca, which had a Play-Doh consistency. Project Row House gave single parents and their children the opportunity to engage hands on in creating the corn people. Meanwhile, as the Tortilla Oracle, Rojas would have the individual place their hands in mixing a ball of masa dough, which would then be made into a fresh tortilla on the spot by community members before he performed the reading. “This led to intimate divinatory conversations,” he adds. Individuals also would create their own corn people to reflect themselves or of a loved one whom they missed.

Rojas was inspired by the Project Row House commitment to art as a bridge for making intimate connections in building the community. He would continue developing his Gente de Maiz project in 2013, when he prepared an exhibition including a corn mandala, video and Tortilla Oracle performances for the MACLA: Chicano/Latino Contemporary Art Space in San Jose, California.

And, as with the Asturias novel, Rojas had found a way to bring forward an ancient practice into the contemporary era without compromising the essential cultural integrity of its original intent and value. This summer, Rojas will become the first artist-in-residence at the Kimball Art Center in Park City, where he plans a project that returns to the concept of Houston’s Project Row House. This becomes the paragon of sensitive, sincere cultural appropriation, an edifying lesson for any artist who falls unknowingly into discovering something similar as Rojas has done while acknowledging its original functional significance and spiritual meaning.

The seeds from the mandala will be gathered, reused and donated after the exhibition, which includes replanting. And, yes, the seeds would make excellent popcorn.

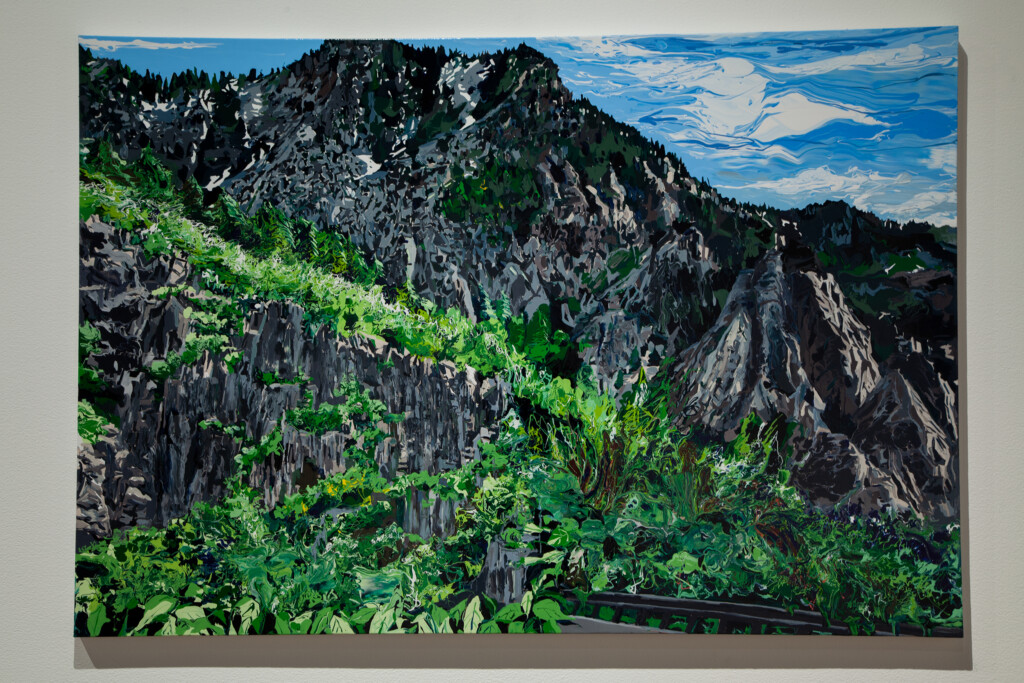

Yujin Kang: Mountainous

UMOCA’s AIR (Artist-In-Residence) spaces have housed truly superlative offerings recently and Yujin Kang’s exhibition is spectacular. Indeed, Utah is fortunate to have artists of Kang’s caliber, particularly in the phenomenal results of how she synthesizes abstract and representative illusion with the surprise of convincing cogency on the canvas.

Kang is a Seoul native who already has established an impressive international portfolio in her work and has lived abroad as well as in Washington, D.C. and New York. She recently moved to Utah, her first sustained engagement in the western U.S. and this fact is central to the impetus of her work.

Kang’s work embodies her creative response to the feelings of her place in the geographical space where she now lives. When she lived in urban centers, her paintings amplified, in part, the signature elements of the city surroundings through the architectural styles of buildings and the ambient effects of natural and artificial illumination on various surfaces. But, more importantly, other elements in the paintings would be created in larger than scaled perspectives or brought forward to engender a mesmerizing illusion of clashing two-dimensional and three-dimensional impacts. Food items such as meat rolls and slabs or ice cream would figure prominently. Kang achieves a dissonance that masquerades effectively as an odd yet feasible harmony in a new sense of the word through the juxtaposition of seemingly incongruous features. The textures of her work are created in part by enamel paint dripped onto the canvas.

Knowing her background, one can appreciate how a new resident such as Kang envisions her first encounters with Utah’s mountainous vistas, the canyons, the highways and signs of human existence even if there is rarely even the hint of an actual human presence, save for vehicles. Many locals likely will identify some of the vistas portrayed in her work but the viewer’s perspective is undeniably transformed. Slabs and lumps of meat appearing is if they had been ingrained in the mountain side are accompanied by generous scoops of ice cream. View the work from a suitable distance in the gallery and then step closely as possible to view the drip enamel technique. The perspective of distance is skewed dramatically but it also never is jarring. What we might take as familiar because we travel routinely through these spaces is reimagined with incisive results by an artist who is enthralled by the natural images of her new home. In one painting, there is a tiny bit of human presence indicated and even then it is absorbed naturally into the canvas so as not to subtract from the magical splendor of its surroundings — figures in a tiny boat on the lake.

No doubt, one rightly can argue that Utah’s visual appeal stands on its pure merits. But, Kang’s exceptional work signals a far more interesting takeaway about how tourists and newcomers might articulate or express their visceral emotions to the environment of a place to which they have been introduced. Or, for that matter, those who have spent all of their lives in Utah, subconsciously reaping their own psychic sustenance from the mountains and canyons.

Annelise Duque: Remember Them Alive

In the contemporary world, the selfie has become the ubiquitous universal expression of one’s cultural identity. Meanwhile, the artist as photographer often takes the opportunity of the self-referential photograph as a first step to pivot creatively to making the viewer aware that it perhaps could become a broader chronicle, for example, linking the past with the grief and pain of loss to the present with healing memories reminding the viewer the essence of embodying one’s heritage in their own identity.

Annelise Duque finesses the nuanced challenge, by leveraging the digital techniques that make her marvelous photographic art possible. She creates work that balances her quest for affirming the familial and cultural roots of her inner existential being with an instructive manifestation that allows the viewer to interpret and adapt accordingly their discovery of how one regards, preserves, reveals and ultimately creates their own identity and being.

Duque, a Filipino-American artist who is a Brigham Young University graduate, creates work that at first glance could have been a cover for an issue of the Better Homes and Gardens magazine from the middle of the last century. The color blue dominates her work, as does the appearance of blue garden gloves in a good amount of her work. In some prints, she appears as a figure, while in others we see only hands. The images incorporate ordinary objects, such as blenders, baskets, clotheslines, swan figurines, mirrors and flowers, all representing the women who have contributed to Duque’s holistic self.

The effects in her photographic art accentuate the liminal or third space that we often navigate in reconfiguring and reimagining the memories of those loved ones who are missed, as subsequently repurpose them for healing and maturing in our inner existential selves. Duque’s art reminds us that a self-portrait often presents an impossible image that cannot be replicated in reality. What Duque presents in her exhibition is emancipating. We can never represent the reality of how others see us physically but we also have the capacity to reconcile our other selves to accepting and affirming the holistic bundle of ancestral and familial roots that encompass our unique hybrid identities.