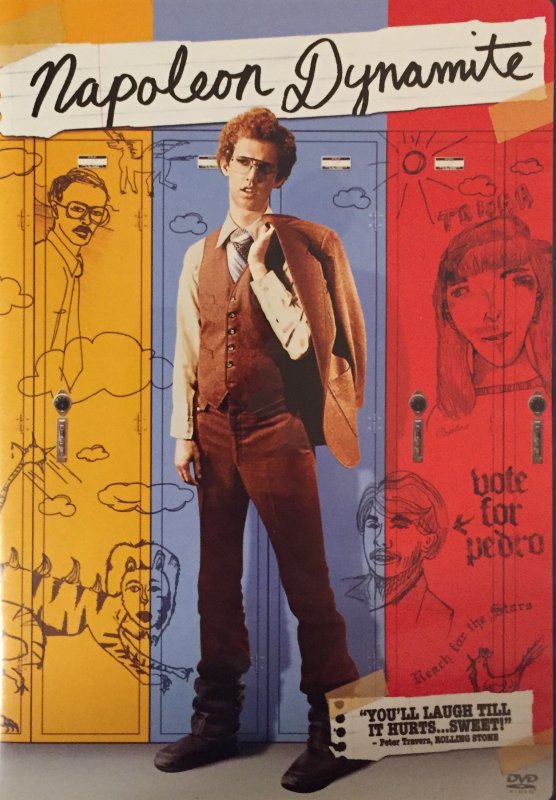

There are many reasons why the sleeper hit comedy Napoleon Dynamite (2004) deserves to be the pride of the Utah film industry. Directed by Jared Hess and written by Hess and his wife Jerusha, it has become a timeless pop culture staple featuring authentic characters and tropes who epitomized the high school scene that remains familiar in Utah and Idaho.

It has been 15 years since the film premiered at Sundance and it later opened in a summer theatrical release, which expanded quickly from six theatrical screens to more than 1,200 at the height of its box office momentum. Napoleon Dynamite has secured its place not just as a cultural icon of a particular period but also as a long-term capital asset that still will have its legs decades later in the film library.

To mark this milestone, the nonprofit Utah Film Center (UFC) will present a screening of the film along with a VIP photo opportunity reception and a veritable high school reunion of Napoleon Dynamite’s key principals for the post-screening talkback. Arguably, this is the first time in many years that so many of the actors and creative team members will appear together. Ticket proceeds, which are tax deductible, will support the UFC’s Artist Foundry program.

The event will be held May 3, starting at 5:30 p.m. (screening at 7:30; Q&A at 9), at East High School (840 South 1300 East) in Salt Lake City – a most appropriate venue.

The Napoleon Dynamite alumni attending include Jon Heder (Napoleon Dynamite), Efren Ramirez (Pedro), Emily Dunn (Trisha), Shondrella Avery (Lafawnduh) and Aaron Ruell (Kip) with Jared Hess (director/writer), Jerusha Hess (writer), and Jeremy Coon (producer/editor).

The genesis for the film occurred 18 years ago when Hess and Heder, students at Brigham Young University (BYU), made Peluca (a Spanish word which translates as ‘wig’ in English), a short in which the film’s lead character made his first appearance. Made for $500, the film debuted at Slamdance in 2003. As Coon recalls in an interview with The Utah Review, Peluca’s enthusiastic reception at the film festival emboldened him and the others to pursue turning the short film into a feature-length version, a decision they already had made.

Coon says the scripts for both the short and feature-length versions came together quickly because the creative team shared the high school experiences that became part of some of the film’s most memorable scenes and quotes (which justifiably have been transformed into countless memes today). “In the prom scene [where Napoleon tells Deb ‘I like your sleeves. They’re real big.’], Jerusha wrote it remembering when she wore a dress with homemade sleeves,” Coon explains. “We always were focused on bringing every scene to some level of authenticity.”

Likewise, Hess had run for class president when he was in high school. His siblings worked at a chicken farm. And, yes, the farmer who shot a cow in front of a school bus packed with kids existed in real life. It is this bounty of credible touches that has lifted the film into its own timeless position in the pop culture canon even as elements of the film date specific artifacts of a particular generation.

And, of course, there is the talent show dance near the film’s end, a moment that crystallized the film’s popularity at its Sundance premiere. Coon recalls how anxious they were to see what the verdict would be, as Napoleon Dynamite’s three premiere screenings occurred within an 18-hour period. Hess, Heder, and the others had taken a major risk, as the film opens with no title and in a high school classroom. As audiences cheered at the end, Coon recalls Hess saying, “we got this. We did it.”

Heder’s dance was not choreographed. It was as impromptu and improvised as any sequence could be. The main song for his inspiration was Jamiroquai’s Canned Heat. In its edited form, Heder’s dance performance flows because he connects so naturally to the spatial relationships of the body and movement in character, which arises from his own high school experiences.

Coon says editing the film was a major challenge. He worked nonstop for eight days and after Sundance, he spent at least another two months honing it for its theatrical distribution. In 2004, before the digital age had been perfected, films selected for Sundance had to be put into 35-mm, cut and colored for their formal premieres.

Napoleon Dynamite was made for $400,000 but its initial box office run generated more than $46.1 million – an outstanding performance for a film that premiered at Sundance. In fact, it ranks ninth among Sundance films in terms of its box office performance for its first theatrical distribution.

It is a notable accomplishment for a film with strong Utah roots. Well-known Utah playwright Eric Samuelsen, a retired BYU faculty member, characterized Napoleon Dynamite as “the one genuine crossover hit of the entire Mormon film movement.” Noting that it was made by a Mormon film director, starred a Mormon actor and its story echoes life in a mainly Mormon community, Samuelsen explains that “its outlook and approach are more directly informed by a thoughtful examination of Mormon culture than even the HaleStorm comedies.”

Samuelsen puts its well: “For an independent film to succeed, the film itself has to be the star. Audience members have to be attracted to that film, usually because they have heard about it, heard that it is offbeat, unusual, that its story is not structured the way most traditional Hollywood narratives are structured, or because it is amusing or provocative in ways standard Hollywood films often are not. This is precisely the case with Napoleon Dynamite.” And, as he notes, when Fox Searchlight, the distributor, advertised the film, it highlighted those elements.

Tickets for the event are available at the Utah Film Center web site.