In Life Animated, the magnificent documentary about a young man diagnosed with autism as a child who learns how to communicate with his family and express his emotions and thoughts by immersing himself in the world of Disney animation, Owen Suskind is unquestionably the leading man in this award-winning film.

In Owen’s story, that plain statement contains several deep epiphanies that has transformed the lives of his parents, Ron and Cornelia, and his brother, Walter. However, it goes even broader for how it inspired the story-telling techniques director Roger Ross Williams used to bring Owen’s story to the screen. Owen’s story also has propelled researchers at some of the nation’s most prestigious institutions to explore affinity therapy while Suskind and others have launched several projects that include a mobile virtual companion application for parents of children with autism.

In January, the film earned director’s honors at the Sundance Film Festival for Williams, who had won an Academy Award for his 2010 short documentary Music By Prudence. This month, on behalf of the Suskind family, Williams will accept the sixth annual Peek Award for Disability in Film by the Utah Film Center.

Williams will attend the award presentation, which includes a free screening of the film along with a Q&A discussion moderated by RadioWest host Doug Fabrizio and including Barry Morrow, the Emmy and Academy Award winning writer/producer best known for his original story and screenplay for the 1988 Best Picture, Rain Man. The presentation takes place Nov. 9 at 7 p.m. in the Jeanne Wagner Theatre at the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts.

Based on the 2014 book with the same title (Kingswell, which is an imprint of Disney Publishing Worldwide) by Suskind, a Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, the film chronicles the story of his son who disappeared from the interactive communication world at the age of three due to autism. Ron and the others in the family began to realize they are able to crack Owen’s silence by way of Disney’s most famous and successful animated films.

As Dr. Dan Griffin, a family therapist explains in a companion article on the film’s website, “Owen was using themes and segments from the movies to connect the way many people may use sports standings, politics, and the weather.” The film follows Owen as he transitions to adulthood. He moves to an apartment in an assisted community, lands a job at a movie theater complex, and experiences the coming-of-age issues that any young audit has, including breaking up with a girlfriend.

There is a clip showing Owen speaking at an international conference. As Suskind mentioned in a recent interview with The Utah Review, Owen and his brother, Walter, spoke this past week in Orlando at the national convention of The Arc of The United States, the country’s largest community-based organization for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

The film project was a perfect match for the Suskind family and Williams. Suskind, who has covered executive branch leadership and has written five other books, won a Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for his national affairs reporting at The Wall Street Journal. Williams won the Oscar for his short documentary about Prudence Mabhena, a young musician from Zimbabwe who was born with severe disabilities and who was abandoned by her social community who feared that she was cursed by witchcraft. Williams, who has won many honors for his work such as God Loves Uganda (2013), also has worked on films touching on racism and the American minorities’ struggles with being able to travel and move about freely. His latest project is a film about the prison industrial complex.

©A&E IndieFilms, courtesy of A&E IndieFilms – Credit: Olivier Lescot / Mac Guff.

Williams directs in a uniquely sincere, empathetic voice for capturing stories of the outsider and others who defy the labels of limitation imposed upon them. Suskind says the film opens everybody’s views to realize that Owen is really just one of a million others who are in plain sight waiting to be validated just like his son has experienced.

Suskind and Williams had known each other at least since 2001, where both had worked periodically for ABC News and Nightline when it was hosted by Ted Koppel, and for LIFE 360SM, an interactive broadcasting partnership for ABC and PBS (Public Broadcasting System). After Williams had finished work on God Loves Uganda, the award-winning documentary that also premiered at Sundance in 2013, the two met for breakfast in the Boston Harbor.

“I had just handed in the galley proofs for the book and I told Roger that I think it would make a good film,” Suskind says. “Cornelia and I had been thinking about how the film story should be told and that it should be honest. The key was that Owen would be the main character and his brother [Walter] would be the primary supporting player. It would completely be Roger’s movie.”

Williams did an exploratory shoot of Owen and Emily [his former girlfriend but with whom he remains friends] at a Valentine Day’s school dance. “I wanted to gauge Owen’s reaction to the camera and I immediately saw this incredible, charismatic person,” he explains. “And then we struck gold, realizing that the best way to tap into Owen’s brilliant creative mind was to incorporate what he was most familiar with – watching the TV screen.”

Williams adapted the Interrotron technique, which many film lovers will recognize as a tool used successfully by filmmakers such as Errol Morris. Williams posted a camera behind a screen so that Owen would look at the director’s image while looking directly into the camera at the same time. Likewise, Williams also played Disney film clips on the screen. Thus, the audience is brought directly into Owen’s mind and his story – as well as into the numerous clips from Disney films. Indeed, the viewer is struck by just how much Owen has to say and the mature, intelligent depth of how he explains his world.

When the film was completed, both Suskind and Williams knew that Owen would be the most important critic to say if the film honestly portrayed his story. “It was a bit suspenseful because we know that Owen can only tell the truth,” Suskind recalls. After the screening, Williams says Owen’s reaction was the greatest feeling he has ever experienced as a filmmaker. “He hugged me and screamed, ‘I loved it!’ Williams adds. “I knew we had captured Owen’s world for the audience to see and understand his reality.”

The film is outstanding for how it chronicles the complex path of a family discovering Owen’s unique affinities and what they mean for his cognitive, intellectual, social and emotional development. Viewers learn of the first instance, when a younger Owen (at the age of six) exclaims, “jucervose” — “just her voice” – a simple phrase from the 1989 Disney film The Little Mermaid. It occurs in the scene when the Sea Witch, the story’s villain, explains what Ariel (the mermaid) would have to give up in order to become human.

Before the family understood the therapeutic effects of what was occurring, Suskind indicates that he even padlocked the television in hopes of discouraging repetitive behavior –a commonly held clinical view regarding autism that had been around since the 1940s. However, the family soon learned that it was through repetition how Owen processed the reference and ultimately made the emotional connection.

By watching Aladdin (1992), Suskind made a significant breakthrough in dialogue between Iago the parrot and Jafar, the movie’s villain. Suskind assumes the Iago character and repeats the line about Jafar marrying the princess and becoming the chump husband. Owen responds and mimics Jafar’s sinister voice with stunning likeness to the work of actor Jonathan Freeman, right down to the subtle British accent as he pitches the line, “I loooove the way your fowl little mind works,” and laughs. Suskind recalls the breakthrough with rightful triumph.

Owen’s immersion in Disney animation is no idle or trivial assertion. There is a scene where he leads a social club where the group watches and discusses the films. The cameo appearances by Jonathan Freeman and Gilbert Gottfried delight the audience as much as they thrill Owen. Honestly, one might even feel just a bit embarrassed about ever having criticized Disney animated films after witnessing just how powerful of an impact they had not just on Owen but also his family.

In Owen’s case, Disney animation became the crux of the family’s discovery of affinity therapy. There are other notable examples of affinity therapy’s value: Rupert Isaacson’s The Horse Boy: A Memoir of Healing (2009, Back Bay Books) and Thinking in Pictures: My Life with Autism (1995, Vintage Press) by Temple Grandin (a past Peek Award recipient).

The film’s most enlightening and touching moments come as the family realizes that Owen identifies with the pantheon of Disney sidekick characters: Baloo, the bear, and Bagheera, the black panther from The Jungle Book (1967), Zazu the hornbill from The Lion King (1994), Sebastian the crab from The Little Mermaid (1989), Timothy the mouse from Dumbo (1941), Mrs. Potts, who is in charge of the castle’s kitchen, and Lumière, the maître d’, from Beauty and The Beast (1991), and many others.

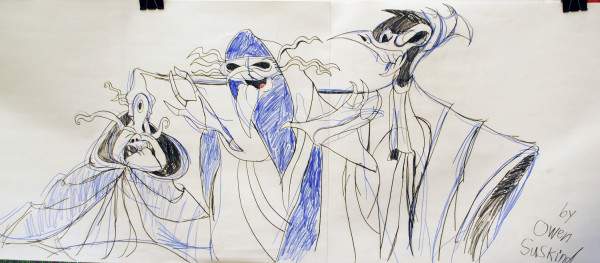

Viewers see how Owen, a talented illustrator who captures the image of sidekicks accurately. He understands what a sidekick is – “helps the hero fulfill his destiny” and he adds, “no sidekick gets left behind.” This is perhaps the most essential epiphany not just for Owen and his family but also for every other parent, family, doctor, therapist and teacher who works with children and adults on various points of the autism spectrum.

The optimistic rewards of Owen’s story came with tremendous effort. There are frustrating moments for Owen and his family. Some of his classmates are moving on but Owen’s lack of progress leads to him being ejected from the lab school. Later, he is upset about his girlfriend breaking up with him but decides he wants to remain friends with her (which Suskind, in the interview, says has been realized). It is through Owen’s insightful embrace of those animated sidekicks that invigorate his most robust phase of emotional and intellectual development to experience and comprehend the same complex human emotions that really do confound and bedevil all of us.

Williams turned to perhaps the world’s most gifted animation artists from France to visualize Owen’s story – The Land of the Lost Sidekicks, which also is the final chapter in Suskind’s book. The animation was created by members of the Mac Guff studio who remained after most of the studio had been sold to Universal Studios and Illumination. Philippe Sanrier, Mathieu Betard, Olivier Lescot and others bring to life Owen’s story in a rush of gorgeous, warm empathetic tones and characters who battle the monsters that parallel those Owen has confronted in his own life.

The film’s impact has unleashed a torrent of activities for family, researchers, developers and others. Family members have speaking engagements scheduled well into next year. Owen’s sidekicks story is generating commercial and retail interest. The film’s website is a growing repository for resources and interactive platforms for information about affinity therapy.

For example, the Affinities Poll is a questionnaire to collect data about what types of affinities and deep interests individuals with autism have and how families are helping to deepen those interests. There is a gallery of submitted images, testimonials and videos. “There has been an avalanche of family response,” Suskind adds. In Owen’s story, it was Disney animated films. For another, it was Japanese anime that motivates the individual’s affinities. In another, a parent found that her son had immersed his identity in black-and-white films from the 1940s.

Suskind also has crowdsourced technology engineers, neuroscientists and clinicians to create mobile and multi-media applications for those with autism under the name Sidekicks. The tools will be adaptable to all mobile and computer platforms.

The film has earned numerous honors, including audience awards, from international film competition venues, including Budapest International Documentary Festival, dead CENTER Film Festival, Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, Heartland Film, Nantucket Film Festival and the San Francisco International Film Festival.

The Peek Award honors the legacy of Kim Peek of Salt Lake City, the savant about whom the film Rain Man is based. Peek, who died seven years ago and was misdiagnosed as autistic during his formative years, stood out for his encyclopedic knowledge of subjects on an unprecedentedly broad scale of intellectual knowledge and pursuits. As noted in his 2009 obituary which appeared in The New York Times, Peek “was the Mount Everest of memory,” as Dr. Darold A. Treffert, an expert on savants who knew Mr. Peek for 20 years, described him.

Previous Peek Award recipients include Dr. Temple Grandin, Carrie Fisher, Sean Fine and Andrea Nix Fine, Sam Berns, Jason DaSilva, and Matt Fuller and Carolina Groppa.

The Peek Award is sponsored by Utah Autism Foundation.