It has been nearly 30 years since Robert Mapplethorpe died of AIDS at the age of 42. In a career that blossomed rapidly within a decade, Mapplethorpe set new stakes as an artist-photographer. However, during his life, his work also was commingled with protests by politicians and the Christian right-wing, which gained huge political influence during the Reagan years, and triggered unwarranted fears during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and censorship of creative expression. Mapplethorpe’s death did not end the controversies. This included, of course, the first arrest and jury trial ever of a museum director, Dennis Barrie, who served as the director of the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center.

H. Louis Sirkin represented the museum in the Cincinnati case and it was his “pitch that people should be able to view what they wanted [that] proved as effective as the case for Mapplethorpe’s artistic value. After the trial, Barrie was contacted by three members of the jury, who told him that they were ‘infuriated that the judge would not let us see all the work.’ The prosecution’s campaign to keep the rest of the photos from the jurors had backfired.”

There still are some people who insist on linking the political controversies of the time to Mapplethorpe’s works in trying to assess them through a 21st century lens. However, recent exhibitions have focused instead on the enduring power of his artistic vision. As Isobel Parker Phillip, who has curated a show of his work, explains, “By celebrating his own sexual identity and memorializing an increasingly visible community of gay men, Mapplethorpe afforded greater visibility to queer narratives. His work paved the way for subsequent generations of photographers and artists who continue to push the limits of representation and celebrate and explore their own identity. His works are as inspirational and challenging today as they were in the 70s and 80s when they were first displayed.”

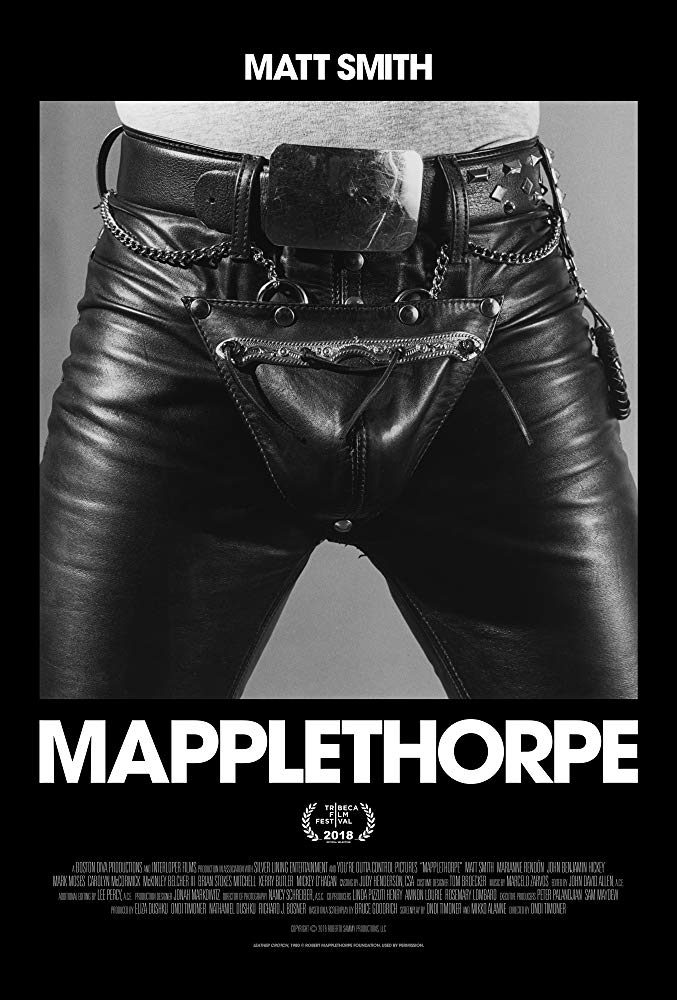

Ondi Timoner, award-winning filmmaker who has carved out an impressive record of documentary works, ventures for the first time into the dramatic feature category with Mapplethorpe, a biopic filmed in Super 16-mm, with occasional moments in 8-mm that evoke a documentary feel. After being in the works for more than a dozen years, Mapplethorpe has been completed and has gained good traction this year on the film festival circuit. Timoner, in a phone interview with The Utah Review, says that includes five audience awards at festivals just within the last three and a half weeks.

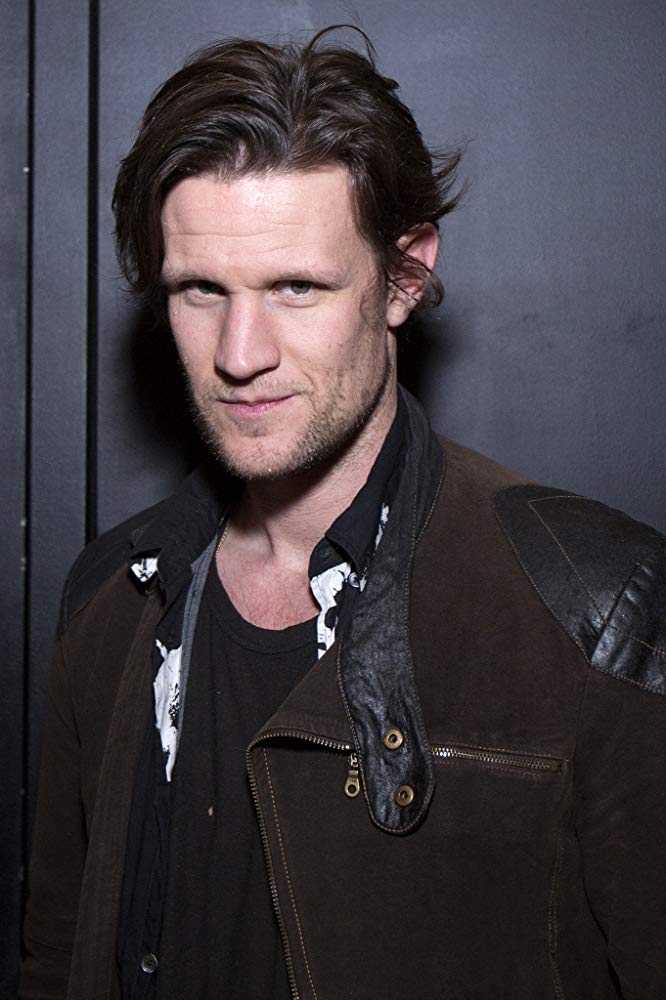

The film, which was commissioned by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, stars Matt Smith of Doctor Who renown who also played Prince Philip on The Crown and Marianne Rendón, who plays Mapplethorpe’s close friend and collaborator Patti Smith.

The film will screen Tuesday, Oct. 16, at 7 p.m. at the Jeanné Wagner Theatre in the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. The free public program presented by the Utah Film Center will be followed by a Q&A with Timoner.

Timoner says she was drawn to Mapplethorpe, whom she describes as the same sort of “impossible visionary character I have taken on in my work.” She won the Grand Jury Prize twice at the Sundance Film Festival — Dig! (2004), a documentary about the American rock bands The Dandy Warhols and the Brian Jonestown Massacre, and We Live in Public (2009), a film documenting the life of Josh Harris, one of the earliest internet entrepreneurs who enjoyed success and was inspired by the narrative premise of The Truman Story film (1998) to create a controversial project in which 100 people would live in a huge terrarium-like space below street level in New York City, all while under continuous video surveillance.

In 2014, Timoner’s TEDx Talk titled When Genius and Insanity Hold Hands, given at the TEDxKC conference, noted that Harris had been ridiculed, especially after a SWAT team from the New York Police Department shut down his project in 2000 for fears that it was some kind of millennial cult. But, a decade into the Facebook era, she explained that Harris had been vindicated. “It became clear that the bunker had come true,” she added.

More significantly, Timoner’s TEDx Talk broadened its thematic point and it explains nicely why she was drawn to telling Mapplethorpe’s story. “But at the center of every world I explore there’s always someone who can’t help but do what they do and they do it against all odds,” she said. “Their lives inherently matter because they envision something greater than themselves which they’re determined to make real. I call these people impossible visionaries. Because they’ve all been told that what they’re trying to do is impossible and they frustrate the people around them with their impossible behavior as they plow forward anyway.”

Thus, the film shows the young Mapplethorpe, who was not particularly interested in photography at the outset, clipping images from magazines and various publications for collages. His artistic impulses unfulfilled, he takes up the camera, a Polaroid at first. As he develops his technique and compositional style, there are the works leading to some of his most recognized and famous art: X, Y, Z portfolio of S&M images, floral still life photographs and, of course, the nudes.

The Mapplethorpe Foundation gave Timoner volumes of materials for her research. Sources for the film included Patricia Morrisroe’s biography published by Random House in 1995, which provided the basis for telling the story of his early adulthood years marked by his unease with the roots of his upbringing in a white middle-class family with Republican and strict Catholic values. These years included musician Patti Smith, who with Mapplethorpe, were penniless dreamers trying to survive in New York City during the late 1960s and early 1970s. There also is Samuel Wagstaff, a rich art collector and curator who guided Mapplethorpe’s formative career developments. Morrisroe’s biographical treatment also detailed numerous sexual encounters, including Mapplethorpe’s well-known obsession with black men, which was captured in the famous Black Book published in 1986.

Timoner also used a lengthy New York Magazine article How Edward Mapplethorpe Got His Name Back as the basis for developing the story line between Mapplethorpe and his brother, Edward (played by Brandon Sklenar), who is a well-known photographer in his own right. The film includes a scene with Edward, 13 years younger than his brother, sharing a paper he wrote about Robert for an assignment in a photography class. Later, after Edward, who has been working as an assistant for his brother, plans to set out on his own career, his brother insists that he uses a different last name (Maxey). Edward took his original name back in 1998, nine years after his brother died.

While the project was more than 12 years in the making, Timoner says they had 19 days to film 155 scenes — even more remarkable when one considers that there were 58 rewrites for the screenplay. Timoner says she remembers that number clearly because she had to count it for Writers Guild of America documentation. In 2010, James Franco was originally set to play Mapplethorpe but pulled out two years later. It was another year before Smith was cast. The decision to cast Smith, in part, was urged on by Timoner’s son who was a passionate fan of Smith’s work on Doctor Who. When she met Smith, her son’s instincts had been confirmed, as Smith reminded her instantly of the character she had been writing.

The current award tally sits at six but with the spate of recent audience award honors, the film is likely to expand significantly on its total. The film’s North American distribution rights also have been acquired by Samuel Goldwyn Films.

Timoner also will join an Oct. 15 7 p.m. screening of Wild Nights with Emily, a 2018 biographical narrative about Emily Dickinson, directed by Madeleine Olnek. Timoner and Olnek will participate in a post-screening discussion, moderated by Doug Fabrizio, host of KUER-FM’s RadioWest. The discussion will focus on the challenges of making a film about historical figures. That program also will take place at the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts.

For more information about the screening, see the Utah Film Center website.