Among the most prominent recurring elements in Toni Morrison’s novels are the roots of the small town black community in the South, even when the stories and characters are living and working in the North. Take, for example, Jazz (1992), a story set in Harlem where both main characters left the South because of the virulent racism of their white neighbors but yet remain incontrovertibly shaped by their rural Southern roots.

Essayist John Duvall recalls, in the opening essay of Unflinching Gaze: Morrison and Faulkner Re-Envisioned (1997), an early interview with Morrison in which she responded to a question that white readers might not understand a particular scene in her writing. Referencing the genre of jazz – “open on the one hand and both complicated and inaccessible on the other” – she explained that William Faulkner “wrote what I suppose could be called regional literature and had it published all over the world. It is good – and universal – because it is specifically about a particular world. That’s what I wish to do.”

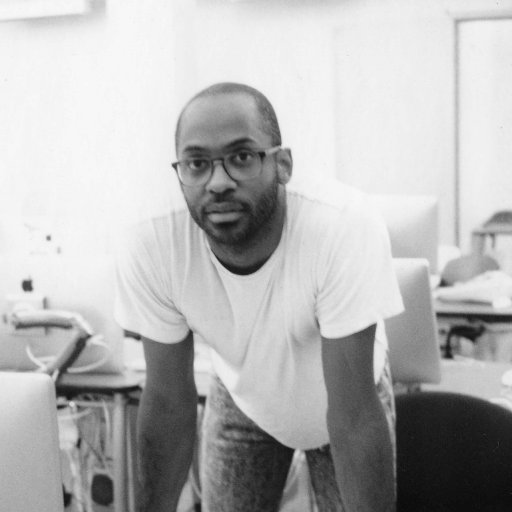

In 2009, RaMell Ross, photographic artist, writer and filmmaker, moved from Washington, D.C. as a freelancer to Greensboro, Alabama, a town of just 2,700 people which is the seat of Hale County. Ross took a job as mentor and basketball coach with a job training and GED (high school equivalency diploma) program to help young people. Over the next three years, he cultivated many relationships and captured the town and its people in photographic images. Then, in 2012, he began five years of filming, collecting more than 1,300 hours of footage.

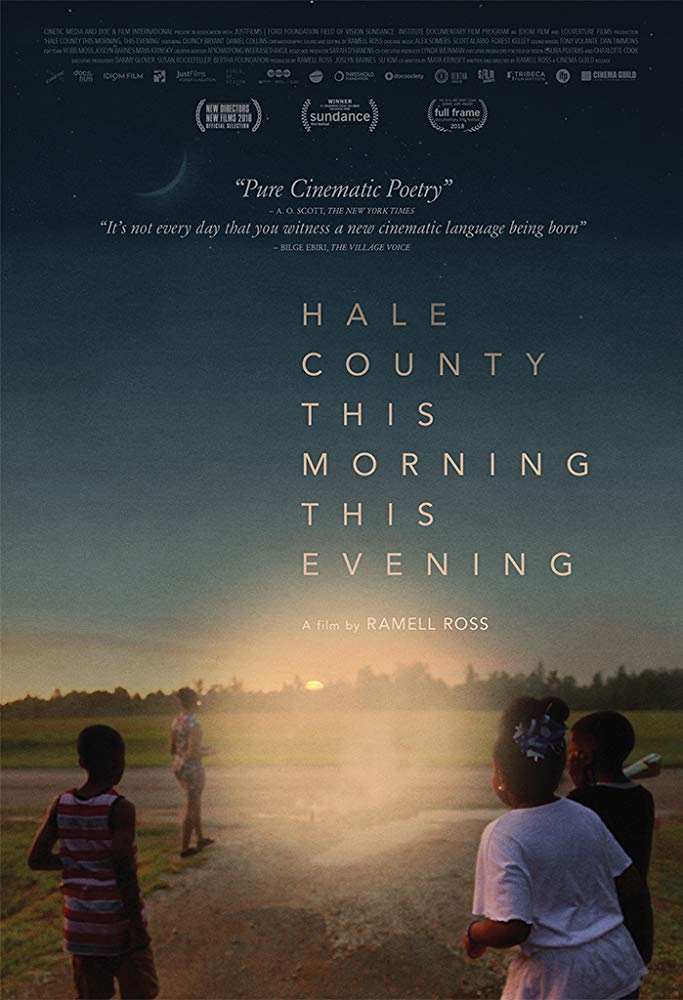

The project became the documentary Hale County This Morning, This Evening, which has gained widespread attention since its premiere at Sundance 2018, along with more than a dozen awards and honors, at least. These include winner for best documentary at the 2018 Gotham Awards, Special Jury Prize for Creative Vision at Sundance and grand jury prize in the 2018 Full Frame Documentary Film Festival.

The film will be presented Wednesday, Dec. 12, at 7 p.m. by the Utah Film Center as part of its Through The Lens Series, coordinated with RadioWest on KUER-FM. Ross will participate in a Q&A moderated by RadioWest’s Doug Fabrizio following the free, public screening, which will be held in the Jeanne Wagner Theatre of the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts in downtown Salt Lake City.

The 72-minute documentary focuses primarily on two African-American men, Quincy Bryant and Daniel Collins, in the small Alabama town, but the film also immerses the viewers in the lives of other residents in Hale County, especially Boosie, a woman who must contend with a family tragedy. Quincy is striving to give his child a better life and educational opportunities. Daniel attends one of the nearby HBCUs (historically black colleges and universities), Selma University, where he plays basketball (the school is more than 140 years old) and hopes to play professionally. The documentary includes exceptional footage on the basketball court. Ross had his own dreams of a pro basketball career when he attended Georgetown University on an athletic scholarship but persistent injuries ended that dream. In Alabama, Ross coached the Greensboro High School basketball team to a state championship.

Indeed, Ross embraced and engaged himself fully in all aspects of life in Alabama that allows him to capture the historical roots of Hale County and its people in a manner unlike conventional documentarians and closer to the artistic impetus of Morrison with the characters in her novels. In 2015, for a blog post at The New York Times, he shared some of his photographic work from the South and the Alabama community at heart of the film. He wrote, “I’m for an art that tries to erase the horizon. With my 4×5 camera upright, swinging the three-leg, glass-nosed puppet into position, I daydream about a postmodern South, of melanin liberation and a less profit-centered humanity.”

This creative aspiration is manifested with such nuanced beauty in his new documentary. It is the essential respite from the usual cacophony of our obsession with digitally immersive communication and media. The viewer is immersed in stories where chronology or the urgency of time is completely subsumed to the singular, unfiltered presence of the residents’ humanity.

When one thinks of art being made to exemplify a particular place or space, Hale County is a paragon of that creative goal. A good corollary is Kendrick Lamar’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, which poet Hanif Abdurraqib explains is not just about the town or the city “but the true landscape is the human interior — the mind and heart of the characters inside of the city, which makes the city secondary to the internal mental and emotional battles themselves. The city isn’t the actual city of living, as much as it is the city of turmoil that rests in between adolescence and adulthood.”

Ross appropriately finds the parallel poetics in his cinematic vision. One of the most stunning sequences in the film underscores the historical objective in a unique, unforgettable way and is one of the rare moments where Ross actively engages the subject in the footage. Ross sees billowing columns of smoke that come from a pile of used tires being burned. The scene opens with a view from inside a car moving through an obviously rich neighborhood and then it crosses onto a dirt road. It segues immediately into a clip from a silent film starring Bert Williams (1874-1922), Lime Kiln Club Field Day from the 1910s.

Williams was a hugely popular vaudeville entertainer and the film was the first featuring a black actor as star. Williams, a native of the Bahamas, often played characters in blackface stereotypes and he is seen in this clip peeking through trees with great curiosity. Then, we see Ross coming onto the property of a quintessentially Southern house and we see a black man tossing another tire onto the fire. In between snippets of conversation, in which the man learns what Ross is doing and tells him that “we need more black folks making photos in the area and taking pictures and stuff,” Ross inserts another scene from the silent film with Williams.

The historical connection is enormous. Despite Williams’ success as a performer, he had to endure the ignominy of being treated like a second-class citizen in hotels and it persists that despite racial discrimination, blacks always have to be “twice as good,” regardless of their skills, talents, proficiency, education, training, or achievement. Likewise, Ross started the project before the tragic killings of Trayvon Martin and others became disturbingly frequently and those responsible for their murders were rarely brought to bear for their crimes and to give the families of the young people their full and proper justice.

Ross says in an interview with The Utah Review that he had hesitated to use archival footage, an element that many documentary filmmakers have used and he didn’t want to do it for the sake of a trend. However, when he saw the Williams’ silent film, which originally was unfinished but then completed and given a premiere in 2014, he saw a moment that would add the depth of relevance and poignancy he was seeking for Hale County.

Ross says among his creative inspirations include Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (1954-55), a work he considers as a creative “epitome” with “sheer lusciousness.” It is a work many Salt Lake City audiences know well, thanks to its definitive performance by Alex Caldiero, a Utah writer also known as The Sonosopher. He also enjoys the “jarring yet pacifying” aspects of the music created by the late Arthur Russell, a classically trained cellist who became one of the most visible members of Manhattan’s avant-garde and disco music scenes in the late 1970s and 1980s that included several underground dance club hits.

Ross says among his creative inspirations include Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (1954-55), a work he considers as a creative “epitome” with “sheer lusciousness.” It is a work many Salt Lake City audiences know well, thanks to its definitive performance by Alex Caldiero, a Utah writer also known as The Sonosopher. He also enjoys the “jarring yet pacifying” aspects of the music created by the late Arthur Russell, a classically trained cellist who became one of the most visible members of Manhattan’s avant-garde and disco music scenes in the late 1970s and 1980s that included several underground dance club hits.

Ross has been a Sundance Institute New Frontier artist in residence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab. His short film, Easter Snap, will premiere at the Sundance Film Festival next month. It examines five Alabama men, who resurrect the homestead ritual of hog processing in the deep South under the guidance of Johnny Blackmon.

For more information see the Utah Film Center web site.