Call it archive activism. The historiography on the topics of social change in the U.S., queer rights and queer culture is advanced significantly in three documentaries being presented in the Utah Film’s Center’s 18th annual Damn These Heels Queer Film Festival.

In each film, primary sources, archival footage and letters and documents not seen for decades are woven superbly into historical chronicles that anchor effective approaches in setting the canon of queer history. They include Cured, directed by Bennett Singer and Patrick Sammon; No Straight Lines, directed by Vivian Kleman and P.S. Burn This Letter Please, directed by Michael Seligman and Jennifer Tiexiera. Later this week, The Utah Review will feature other documentaries from the festival that also rely heavily on primary source materials.

The films are available for streaming on demand, with purchased tickets, through July 18.

Cured

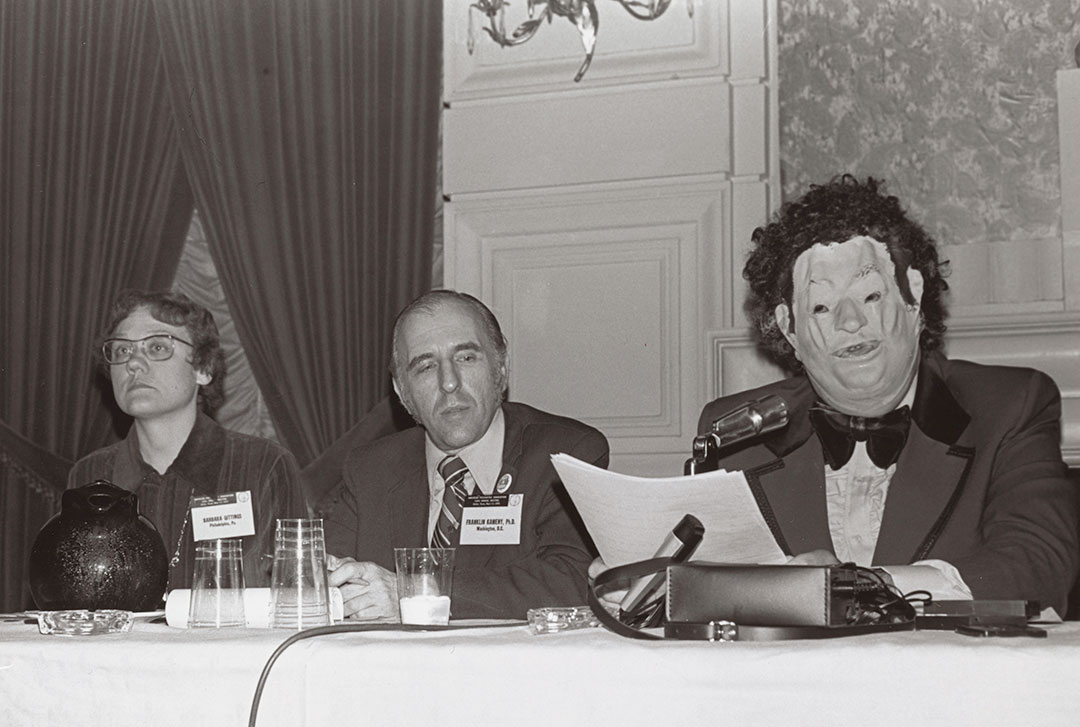

Research and academic conference proceedings often are dry as dust but when psychiatrist Dr. John Ercel Fryer took the stage at the 1972 annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association (APA), he wore a mask that strangely resembled the Leatherface character from the horror film Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which actually came out two years after Dr. Fryer’s unforgettable appearance.

Addressing his peers as Dr. Henry Anonymous, he announced that he is a gay psychiatrist — a move that at the time could have him stripped of his license to practice and derail his career. But, it was more than a well-crafted stunt, as he appeared in a wig, ill-fitting clothes and spoke with a microphone that distorted his voice. It turned out to be a pivotal moment in the campaign by gay activists and APA allies to remove homosexuality from the APA’s official manual, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

Cured, directed by Bennett Singer and Patrick Sammon, is an outstanding exploration of the case study dynamics with regard to the academic politics of science and institutional research’s controversial and dubious response to issues of sexual identity. Singer and Sammon achieve a multidisciplinary impact that resonates not only with queer audiences but also a much broader spectrum of viewers interested in the long game campaign of social change in American history.

Fryer’s moment stands out as a practical storytelling point in framing a documentary that revolves around the typically mundane bureaucratic workings of medical and research associations such as the APA. It is through sequences of committee meetings, conference presentations, memos and policy papers that the organization’s leading purveyors of research views and methodology were able to sustain their power and defined standards of diagnosis and treatment as they believed. In the early 1970s, allies and activists acknowledged the difficulties in surmounting the obstacles. But, as Singer says in an interview with The Utah Review, Fryer’s unexpected tactics set in motion the impetus for the change, producing “such a dramatic moment that justifies the rationale for making the film.”

Singer says he and his colleague were surprised that no one had yet made a film about Dr. Fryer’s dramatic appearance, when they started the project in the middle of the last decade. Twenty-two years after his 1972 appearance, in the APA’s annual meeting in Philadelphia, Dr. Fryer revealed that he was the masked presenter. Sammon had pitched the idea for the documentary, inspired by a screenplay about Fryer’s story, which was written by Charles Francis, the president of the Washington, D.C. chapter of the Mattachine Society.

The film’s use of archival material is masterful, particularly in enhancing the suspenseful and thrilling elements of a quintessential David v. Goliath story that typifies the enormous struggle activists and allies encountered. It documents the period before the 1970s, when every person was automatically considered mentally ill and unfit for jobs in the government as well as in many business sectors. The APA’s designation of homosexuality as a mental illness provided the justification for discriminatory practices which denied queer citizens their civil rights and the benefits of the 14th amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. One interview in Cured recalls a woman, whose life as a teen was affected in devastating ways by the APA”s insistence on a pathological diagnosis. She faced two options: either go to an institution for treatment or marry a man at the age of 14.

Thus, the APA’s stance became the “first domino to be challenged,” as Singer explains, to achieve the turning point in the modern queer rights movements. “And, victory was by no means inevitable,” he adds.

It is impressive how the production team handled an enormous amount of historical materials for the film. There is Dr. Frank Kameny, an astrophysicist who was fired by the U.S. government because of his sexual identity. He publicly criticized the categorization of homosexuality as a pathological disease in the medical literature, some eight years before Dr. Fryer’s pivotal presentation. Kameny and colleague Barbara Gittings were invited to the 1972 APA meeting in Dallas to participate on a panel with two psychiatrists. Gittings recommended that a gay psychiatrist be included on the panel. Dr. Fryer agreed only on the condition that he could remain anonymous. It was a monumental risk, for being revealed would assuredly have ended his prospects for tenure at Temple University and for his practice which involved treating patients at the university hospital.

Other memorable examples of archival footage, not seen in 50 years, include a 1970s segment from CBS Television’s 60 Minutes show on what correspondents characterized as a civil war in the APA on the issue of homosexuality. Another comes from David Susskind’s talk show, when for the first time on American television, a group of lesbians who publicly declared their sexual identities challenged the premise of queerness as a mental aberration. As Singer notes, it was an example of a “seemingly progressive liberal talk show host discussing the topic with a smug certainty about the scientific body of evidence” that the APA had relied on in justifying its position.

The film captures the truly heroic dynamics of activists and how allies effectively framed their roles to aid activists without overtaking leadership positions in the movement. Likewise, the film handily juxtaposes archival footage with current and recent interviews with many key players. It also highlights a realization that time is quickly shortening in capturing direct oral histories from modern pioneers iin queer history, Singer says that since the interviews were conducted, five major storytellers featured in Cured have died.

Another important story thread focuses on Dr. Charles Socarides, a psychiatrist who continued to insist on the pathological diagnosis stance even after the APA had removed it from the DSM. There is an astounding irony that amplifies the historical stakes embedded in the story. Among those interviewed in the film is Richard Socarides, his son, who came out as gay during his teen years. The younger Socarides recalls that his father pulled a gun from his desk drawer after hearing the news from his son. The elder Socarides, who died in 2005, never veered from his beliefs. He insisted that homosexuality resulted because of absent fathers and mothers who smothered their children with attention. The younger Socarides, who served as President Clinton’s adviser on queer rights, believes that his dad did not evolve in his thinking because Dr. Socarides and others like him genuinely believed they were helping people whom they believed were mentally ill.

Cured excels in every regard. It will air on the PBS Independent Lens Series on National Coming Out Day on Oct. 11 of this year. The documentary also is being distributed to colleges, universities and libraries. A 35-minute cut of the film also has been made for use in high schools along with a curriculum guide. The film won Best Documentary honors last year at Frameline San Francisco International LGBTQ Film Festival and NewFest: New York’s LGBT Film Festival, among others.

Singer says the film is being optioned to be adapted into a scripted series with episodes representing the documentary’s key events.

No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics

Published in 2013, Justin Hall’s book No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics offered, as the author described it, snapshots of artists of queer comics’ struggle for recognition. He wrote, “While comics have traditionally been dismissed as puerile and simplistic, queer cartooning has been even further marginalized within the comics world, rarely garnering shelf space in comic book stores or recognition at conventions and award ceremonies.”

More importantly, Hall celebrates what queer comics have accomplished in facilitating an “uncensored, internal conversation within queer communities,” and “hav[ing] analyzed their own communities and their relationship with the broader society in smart, funny, and profound ways.”

Filmmaker Vivian Kleiman brings the foundations of Hall’s research to the screen in the vibrant, sunny, elucidating documentary No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics. Signaling how the film reaches broader audiences beyond the expected target queer demographic, she also has achieved a trifecta envied by every documentarian, as the film was selected for Tribeca, Sheffield Doc/Fest and the American Film Institute’s AFI DOCS Film Festival, among numerous other festivals.

As with other excellent documentaries on the Damn These Heels slate, Kleiman’s film amplifies the encouraging recent trend of historiography not just in queer history but also for the studies of comics in general for their influence in sociocultural movements and community identity building. Sparkling with optimism and plenty of wit, No Straight Lines compacts nicely the transition from the underground scene of a half century ago to visibility and acceptance in the broader realms of pop culture. To wit: Alison Bechdel, who created the long-running comics series Dykes to Watch Out For, stepped into the graphic novel genre in 2006 with the publication of her memoir Fun Home, which became a bestseller and later inspired a musical. The book, published by Penguin Books and cited by The Guardian as one of the current century’s best 100 books, tells the story of how her closeted gay father, living in a small Pennsylvania town, killed himself shortly after Bechdel had come out as a lesbian. Bechdel’s appearance in the film is an essential pillar in Kleiman’s valuable cinematic chronicle.

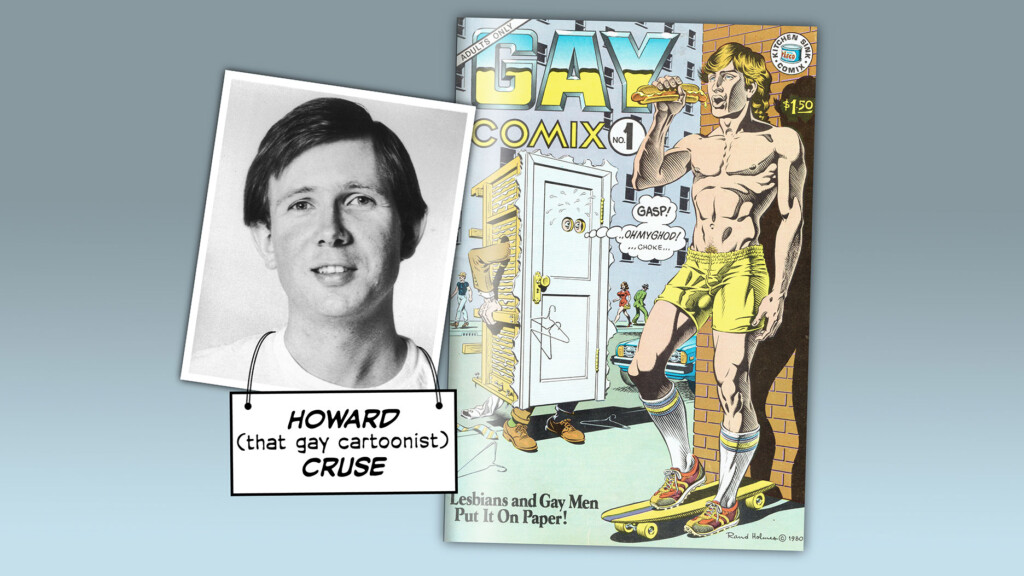

A marvelous film for media studies and social science courses and not just in queer history or queer studies, No Straight Lines introduces viewers to pioneers in the queer comics field including Mary Wings, the creator of Come Out Comics as well as Rupert Kinnard, who created the first Black queer character (Brown Bomber) and Howard Cruse, whose comics dealt with gay rights themes and the AIDS epidemic. Kleiman introduces viewers to numerous contemporary artists along with several scholars, tracing the development of the cultural DNA that has fortified the sociocultural and sociopolitical impact of queer comics. And, as with other documentarians featured in the festival, Kleiman offers a wondrous juxtaposition of archival material and comics art with the interviews she conducted for the film. It becomes the ideal companion piece to Hall’s 2013 book.

Kleiman, a Peabody Award winner who also directed a 2014 documentary Familes Are Forever about a Mormon family accepting and affirming their gay son’s identity, frames the story’s historical anchor in precisely the way that would inspire a new generation of queer comics and graphic novel artists to add their creative voices to the legacy of the two immediately preceding generations of artists who carved out numerous pathways. Kleiman also touches on the commercial realities for artists in the 21st century, who are learning to cultivate niche markets and use social media platforms to promote their work and connect to readers.

She mentions the do-it-yourself modality for web-based comics. “Young people still use pen and paper and sketchbooks and then morph to the electronic format to finish it,”she says in an interview with The Utah Review. The film also focuses on the lessons of sticking with a passion as a patient long-game strategy. She cites how Bechdel worked for 20 years in a daytime job to pay the bills and once her work was syndicated, she was able to quit her job and focus full-time on her art and storytelling. “Also, many artists were tickled to see their art added as images to the film,” Kleiman adds.

She recalls the moment that became the genesis for the documentary, when she was iinvited to attend a major gathering of queer comics artists in 2015. “I walked into the lobby of a college in Manhattan and there was a room full of the most diverse selection of queers in one location,” she says. “There was a non-binary individual with chartreuse-dyed hair engrossed iin conversation with an older, balding gentleman, who was wearing a button-down Ivy League style collared shirt. It was a memorable snapshot of the tone and tenor of intersectionality in the room.” After listening to conference panels over a couple of days, Kleiman says that she was overwhelmingly touched by the new, candid and open approach of storytelling. “It sent that familiar shiver down my spine, indicating that this would be a good subject for film,” she adds.

To give a cohesive, cogent frame to a film that encompasses so many diverse braids and threads of the queer comics form, Kleiman says she realized about three-quarters of the way through the editing process that the organizing meta theme would be how the community of queer comics artists formed around a genuine sense of enjoying each other’s work and riffing on elements that they respected and admired. It is a dynamic that viewers will pick up quickly in No Straight Lines.

P.S. Burn This Letter Please

A bona fide audience pleaser with the archival heft of a documentary capturing the underappreciated significance of cultural developments in a seldom chronicled community and era, P.S. Burn This Letter Please is what a thoroughly researched, eloquent long-form feature in The New Yorker would be if it was translated intact to the cinematic screen.

Directed by Michael Seligman and Jennifer Tiexiera, the film resurrects from obscurity the fine art of letter writing and its artifact value in conveying a history that otherwise would have been vulnerable to being destroyed for fear that it would trigger shame and embarrassment.

An engrossing retrospective taking viewers to the drag culture scene in New York City during the 1950s, the film arises from letters found in a storage unit in Los Angeles in 2014, a few years after the recipient of those letters died. The letters were addressed to ‘Reno,’ who really was Ed Limato, a radio professional turned highly regarded Hollywood talent agent who eventually moved from New York to the west coast. When, Limato died in 2010, The New York Times obituary opened with the following description: “Clad in a salmon-pink Richard James suit, he would charge into the office and rattle the keys to his Aston Martin convertible in a morning salute to his pet fish. Then, with a flourish of his arm, he would summon his three assistants by shouting, ‘Let’s talk to the stars.’”

No doubt, after reading such a flamboyant description, Reno was loved by the drag queens who wrote to him frequently. One of those letters — which became the reference for the film’s title — documented a crime reported in the New York press in 1958. Drag queens Claude Diaz (Claudia) and Robert Perez (Josephine) broke into the Met Opera House and stole many expensive Italian wigs. In the letter, penned by Josephine, which confirms the crime, Perez closed with “P.S. burn this letter please.”

In one of many extraordinary moments in the film that can be simultaneously moving, funny and bittersweet, Diaz confirms the details of the 1958 incident, when they mopped (the word he used to indicate the theft) the wigs. He triumphantly pulls out one of the wigs they stole, as part of a memorable “fuck you” gesture to the police who investigated the crime. When the two men were commanded to return the stolen wigs, they successfully duped the police by replacing the wigs with cheap synthetic makes.

This film is a treasure. It also is a brilliant example of how even the smallest bits of primary source material effectively reconstruct and flesh out historical chronicles well beyond the newspaper and magazine clippings of an earlier time. As noted in the Cured documentary, the 1950s were part of an era when homosexuality was viewed as pathological and the nightclub scene for gays and drag queens was subjected to relentless harassment and police raids. In this film, Seligman and Tiexiera rescue a gold mine of letters and present them along with interviews of many who wrote the letters with the salutation, “Dear Reno.”

It also emphasizes the precarious nature of primary source materials for developing the canon of historiography for queer history. Many of the subjects interviewed in the film were in the late 80s and early to mid 90s at the time of production. Just as other documentaries celebrate and champion the resilience and fortitude of queer communities even as they faced constant threats in a given era, this documentary also preserves and crystallizes a more realistic, comprehensive account of an age that often has been recounted based on sources other than those from individuals directly impacted in the events and stories of their community. One also acknowledges just what a master of networking Limato (a/k/a Reno) had become on his way to a successful career as a Hollywood agent and who had started as an assistant to director Franco Zeffirelli. Everyone apparently adored ‘Reno’ and entrusted him with juicy dishes of gossip and the details of events such as the great Met Opera wig caper. Apparently, Limato must have believed that the memories should never be destroyed. And, how fortuitous it was to find the letters to ensure their archival permanence.