The stories of two introverted queer musicians who express their deep spirituality through their work are told separately in an exquisite pair of films as part of this year’s slate of the Utah Film Center’s 17th annual Damn These Heels Queer Film Festival. They are Variações, a Portuguese biopic written and directed by João Maia, and Keyboard Fantasies: The Beverly Glenn-Copeland Story, a documentary directed by Posy Dixon. Both films are available for virtual streaming for passholders and individual ticket buyers now through July 19.

Variações (Guardian Angel)

This is an outstanding story of cinematic poetry about António Variações, a Portuguese pop rock singer who quickly became popular before he died at the age of 39 from AIDS-related complications in 1984. This film is the culmination of Maia’s effort spread over two decades to craft the right story and the result overflows with love and pride for the unique inflections and voices of Portuguese culture and an extraordinary songwriter.

Everything shines in this film. Actor Sérgio Praia spent nearly a decade preparing for the role. In fact, he portrayed the late singer in Variações, de António, a 2016 play by Vicente Alves do Ó. His physical appearance mirrors that of his subject perfectly although the film casts Variações as more extroverted than he was in real life. Nevertheless, the film conveys the humbleness of a songwriter who never would compromise his art for commercial popularity. To wit: Variações stands out as one of Portugal’s most important contemporary cultural figures some 36 years after his life was cut short by AIDS. Maia’s beautiful homage introduces the rest of the world to his music.

One caution: one should not rush to compare Variações to the likes of, say, Freddie Mercury. The singer, born as António Ribeiro in the town of Fiscal near Braga, wrote lyrics that evoke the roots of where he came from, the joys of love found and lost, the complexities of relations with family, friends and those who struggled to understand and accept who he was. One of Maia’s greatest gifts in the making of this film is how he allows the lyrics to let Variações’ voice speak to the story of his life. It is as credible and compelling as a biopic could be.

Thus, Maia opts for a different path than a more conventional chronological arc in this biopic, especially as Variações was a relatively late bloomer in the professional music business. The film encompasses the last seven years of his life, beginning in 1977. Variações only recorded two albums.

While Variações often was reserved and understated (perhaps surprising for someone who worked many years as a professional barber), Praia’s portrayal scales up the perception of the late singer appropriately for the big screen. Thus, the film bridges elegantly the spectrum of independent art house and mainstream commercial appeal without sacrificing the integrity of the subject and the life story at the cinematic core.

Because Variações’ life was cut short, the mythical proportion is a natural human tendency. Born into a Catholic family, his love for music is evident from his boyhood days. He went into the army and after he finished his military service, he eventually ended up in Amsterdam. When he came back to Lisbon in the 1970s, the climate is homophobic but he stands up for himself. He reconnects with a former lover, Fernando, who is married to a woman and the wife is aware that the two men had a relationship. In fact, Variações’ return to Portugal draws the two men close to each, especially as the singer’s career begins to germinate. However, if there was any friction or tension with regards to the relationship the two men enjoyed, there is no evidence of it in the film.

The focus puts the music at the forefront. Variações assembles a band of talented musicians who have other full-time jobs and he finally signs a recording contract with Valentim de Carvalho in 1978. But, it would be another four years before his first single is released, titled Povo Que Lavas No Rio (People who bathe in the river), a song immortalized by Amália Rodrigues, the legendary Portuguese singer and actor. The music comprised his true public persona. Many of his fans took it as a significant sign when he died on the feast day of St. António, the patron saint of Lisbon. The magic of his life reverberates in Maia’s stellar cinematic tribute.

Keyboard Fantasies: The Beverly Glenn-Copeland Story

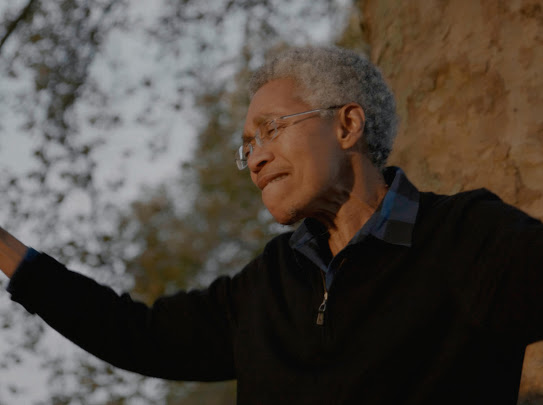

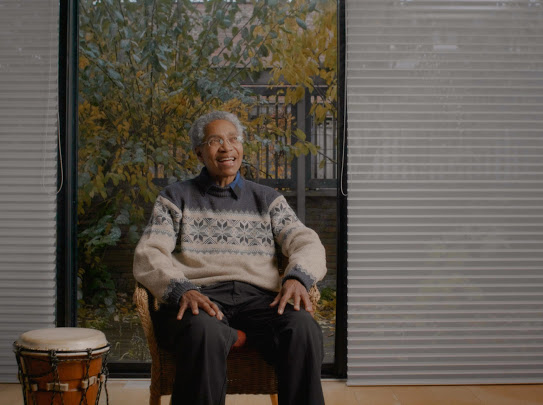

Everyone deserves the absolute joy this 62-minute documentary of Canadian musician Beverly Glenn-Copeland, directed by Posy Dixon, delivers. At 76, Glenn-Copeland, a Black trans man musician who practices Buddhism, has found true Zen in his family and work life. There is a youthful energy that appears inextinguishable and the film is infused with it not just in his presence but also those of the musicians who perform with him—practically all of them at least 40 or 50 years young than him.

He connects with young audiences who appreciate that he does not chastise them for being selfish. His most famous work, the Keyboard Fantasies album, which was released in 1986, has been rediscovered, starting in Japan and spreading throughout the world. Glenn-Copeland is in greater demand than he has ever experienced in his long career. Ironically, an international tour starting in Australia that had been planned this year has now been postponed until next year, due to the pandemic.

Glenn-Copeland’s music might be conveniently categorized as part of the New Age genre but that would be an inadequate label. As Dixon chronicles, the musician’s life took an intriguing path without him feeling particularly resentful about obstacles, real or potential.

He was raised as a Quaker in Philadelphia. The family was musical, as both his parents played piano and Glenn-Copeland was absorbed by Western classical music traditions. After high school, he went to McGill University in Montreal as a classical music major but then he took up folk music but then decided to experiment with it as a hobby.

In Montreal, Glenn-Copeland identified as a lesbian, although Canada had not yet decriminalized same-sex intercourse. He recalls how he finally could wear his hair short, although his mother insisted that he grow it out to look more feminine. However, his liberation did not come without costs. School officials threatened him with expulsion and we learn in the film that his parents secretly had enrolled him for electroshock conversion therapy. In the film Glenn-Copeland makes clear that he was not angry with his parents and he knew they loved him.

In a matter-of-fact way, he explains that in the 1960s his parents were responding understandably to the published sources available at the time which generally concluded that such behavior would have been abnormal. Similarly, he acknowledged his own family roots in contextualizing his reaction to what was happening. His grandmother was the first one not to be born into slavery and he saw how his parents were navigating their own paths of finding normalcy at a time when racial discrimination was widespread. Indeed, listening to him recount the experiences emphasizes just how sincere his commitment to Zen Buddhism really is.

As for his own transition, only about eight minutes is devoted to the discussion, which comes late in the documentary. In the 1990s did Glenn-Copeland finally have the language to articulate his true transgender identity. He was 59 when he came out to the world. Not so ironically, he mentions that even his mother admitted that she knew that he always was a boy but that she did not have the understanding to express what it would mean for her child.

The most joyful moments come when he talks about the process leading up to Keyboard Fantasies. In the 1980s, he was fascinated by the new personal computers and he purchased an Atari, a drum machine and a Yamaha keyboard, leaping into a burst of experimentation in realizing that he had access to a whole new spectrum of sounds not possible with pure acoustic instruments. In the film he recalls his creative process—shovel snow, take care of the family, make music and repeat the cycle over and over.

His most famous album did not have a major release. Glenn-Copeland produced copies on cassette tape and sold a few dozen. Nearly three decades after its release, he was contacted by a collector in Japan, where electronic music with a distinct flair for classical sounds had expanded tremendously with numerous pioneers since the 1970s. Only then did Glenn-Copeland realize that the album, indeed, had gathered quite a cult following. That has led to tours in the UK, Europe and Canada, where he lives with his wife, Elizabeth.

Glenn-Copeland takes all of this in stride with exemplary self-effacement but he sparkles with genuine exuberance that pops out as a remarkable epiphany about the arts and how the opportunities to express one’s true identity have expanded so rapidly, just in recent years. He mentions the loving energy that his audiences emanate, as he recalls how he was so introverted when he would play the piano that he would barely look toward the audience. When he sings the spiritual Deep River in a Canadian performance, the audience is rapt in total silence—an extraordinary performance by an extraordinary musician.