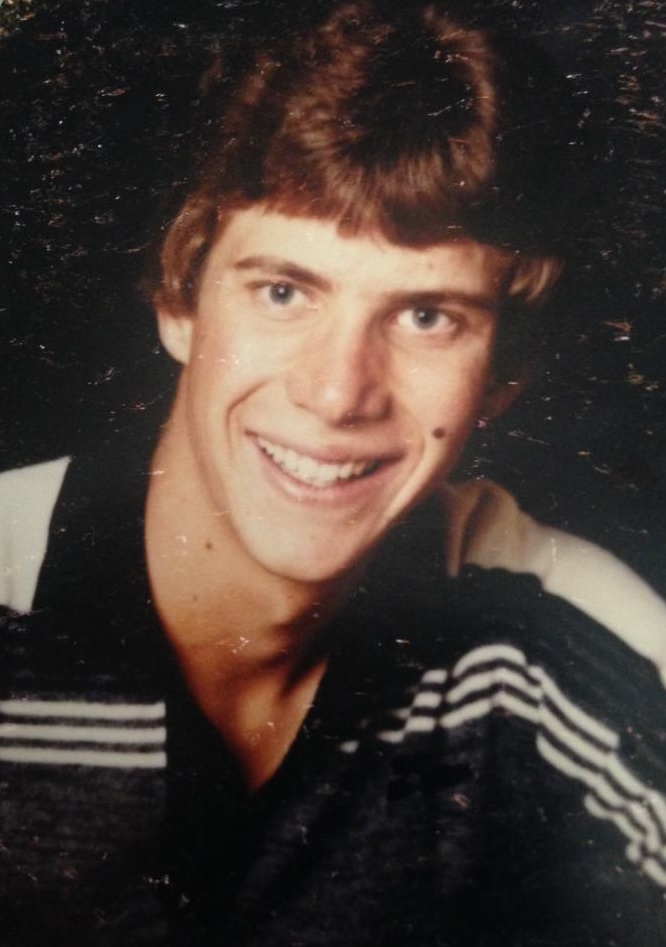

Just as Thanksgiving heralded the holiday season in 1988, news spread through the underground networks of Salt Lake City’s gay community about some of the horrendous details of the murder of Gordon Ray Church, 28, a gay college student from what is now Southern Utah University. Church’s killers were tried and convicted, with Michael Archuleta sentenced to die and Lance Wood sentenced to life with the possibility of parole. Both men are still alive today.

On the 20th anniversary of Church’s killing, Connell O’Donovan wrote a remembrance of the young man. He did not know Church but two of his closest friends did. O’Donovan wrote, “For several weeks, I remember walking around Salt Lake City in a daze: Christmas carols in the malls, Temple Square alit, the Messiah sing-along, the gingerbread Victorians of the Avenues and Marmalade district all lit up; and it was all but ashes in my mouth, compared to the horror of realizing, ‘There but by the Grace of God go I.’ The heart-wrenching vulnerability and visual flashes of the violence committed upon Gordon’s body would crash into my head and overwhelm me at any moment and I would break down crying at the thought that it could have just as easily been me.”

The history of Utah always has been told first within the frame of fulfilling the promise that its pioneers and settlers sought as they moved westward, escaping from the bitter pain and trauma of being ostracized for their religious beliefs. But, as in so much of the American West, Utah’s history also is a violent one where the dynamics of frontier justice and the indelibly etched hammering effects of trauma have reverberated for many generations. Our challenge becomes not only to acknowledge but also to reconcile the historical reckonings.

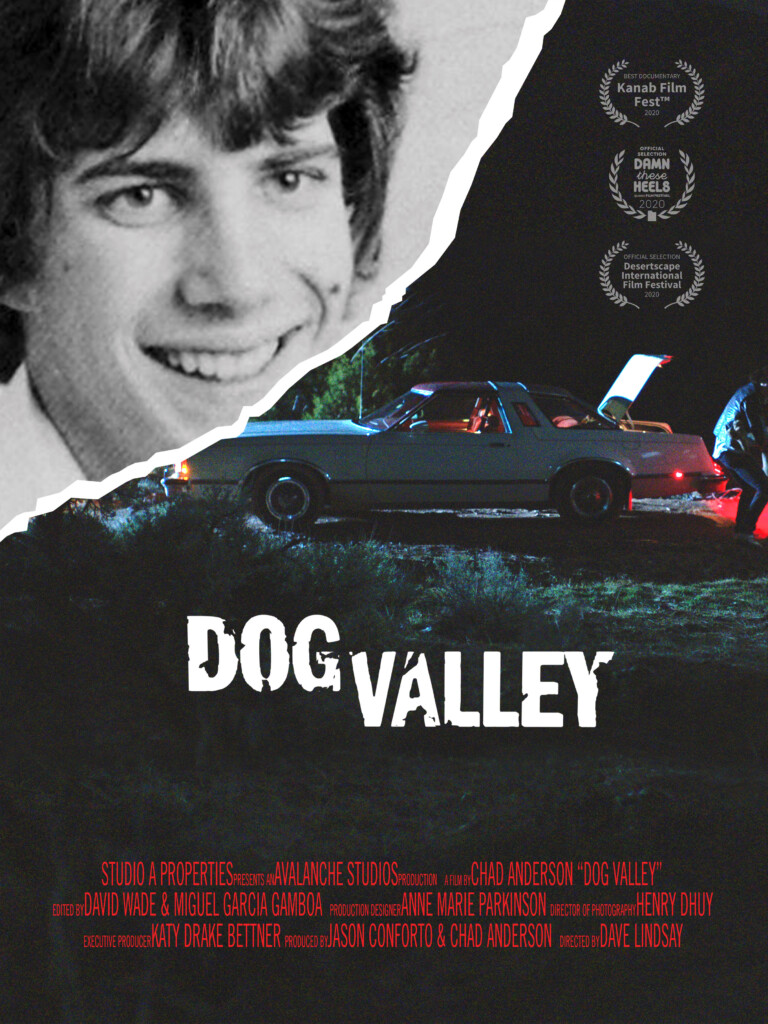

Making its second appearance at a film festival, Dog Valley, an Avalanche Studios production directed by David Lindsay and produced by Chad Anderson, is being screened for the Utah Film Center’s 17th annual Damn These Heels Queer Film Festival. It is available for virtual streaming for passholders and individual ticket buyers, only those in Utah, now through July 19. A Q&A also will be held with Lindsay and Anderson on July 17 at 7 p.m.

An outstanding documentary, the film synthesizes the story of Church’s life and legacy and the complex path toward grace of judgment and justice. Dog Valley excels in articulating the difficult balance of chronicling the details of a murder so gruesome that the presiding judge at trial sealed the evidence and placed a gag order on reporters while showing that the heartbreaking effects of the trauma have never subsided as both friends of the victim and family members of one of the convicted murderers confront grief, remorse and compassion, respectively.

The film arose from a project of passion that Anderson, who was raised as a Mormon in Missouri and Idaho but moved to Utah in 2011, started when he was researching local hate crimes. Trained as a trauma therapist, he says, in an interview with The Utah Review, that he was struck by the number of unsolved murder cases and how so many of them had very little detail. “Gordon’s story stood out for me, with the brutality of the crime and the fact that justice had been administered in his case,” Anderson explains.

At one point, he considered processing his research for an article but with so many details, he decided to pursue telling the story in a documentary format. Eventually, he connected with Lindsay who runs Avalanche Studios in Salt Lake City.

“I had known very little about the case although I had heard about Archuleta,” Lindsay says, who adds that he is drawn to the true crime narrative for documentaries. “I was impressed with the amount of work Chad [Anderson] had done and his passion. The crime case was fascinating, brutal and disgusting along with the things that happened after the crime, which made it even more bizarre.”

Although the project did not have any funding, Lindsay agreed to make it their own effort as a passion project, finding resources along the way. Dog Valley took three years to produce with Anderson and Lindsay’s team working nights and weekends.

The challenge was to pull all of the pieces together into the right compelling frame, a creative task that has been accomplished with strong impact. “Utah has a surprising history of violent crimes and frontier justice through the years,” Anderson explains. “We did not choose to do a narrative track.” This history, of course, includes Utah’s experience with the death penalty. In 1977, after the U.S. Supreme Court lifted the moratorium on executions, the state of Utah became the first to carry out an execution: Gary Gilmore by firing squad.

The film’s detail of the crime itself is voluminous. Anderson traces the point from where Gordon, a native of Delta, Utah, stopped at a 7-11 store to purchase cigarettes to when he was abducted by Archuleta and Wood and to the brutal torture, sexual assault and murder he suffered in a remote spot in Millard county and finally, where his body was dumped in Dog Valley.

Church’s murder was the second extraordinary gruesome killing in the area within three years. Sharon Sant, a 19-year-old student at the same school that Church attended, disappeared Aug. 1, 1985, while hitchhiking to a friend’s funeral in Fillmore. Her decapitated and dismembered body was found in a shallow grave near Cove Fort two weeks later. Her killer was convicted two years later but it was thrown out when the judge learned that a juror had brought a press clipping about the case to the deliberations. Wesley Hamilton was convicted in a new trial and sentenced to life in prison.

As Anderson notes, he was interested to see if and how homophobia or narrow mindsets played a role, as he examined the local law enforcement authorities’ investigations of Church’s murder. As the film emphasizes, the police were the utmost professionals with the courtesy one might expect in a small-town environment. Indeed, the police and investigators who appear on camera during the film were deeply affected by the utterly heinous nature of Church’s murder. One of the officers knew Church’s family (who are not interviewed in the film and their request for privacy was honored), who lived just four houses away in the neighborhood.

There never was any doubt that the Millard County sheriff’s office was going to pursue justice for Church’s murder with all available means. As local LGBTQ historian Ben Williams noted in a QSaltLake magazine column in 2009, regarding the gag order on the press covering the trials, “It was rumored that the judge did this to protect Church’s prominent LDS family from Delta from the scandal, but those who know the family said it would not have mattered. They simply wanted justice.”

Many in Utah were certainly more familiar with the details of Matthew Shepard’s murder in Laramie, Wyoming, which occurred some 11 years after Church died. However, Anderson, who was allowed to review the evidence in detail (as shown in the film), says that Church’s death was more intense and bloodier than Shepard’s killing. When Archuleta was tried for the murder, the coroner who conducted the autopsy was on the stand for two and a half hours providing details of his findings.

Lindsay and Anderson handle the task of telling such gripping, shocking details without sensationalizing them, while being scrupulously sensitive to the need for dignity and respect, wherever appropriate. Many of Dog Valley’s most impressive moments come in chronicling the dimensions of personal relationships on both the victim’s side as well as those of his two killers.

Archuleta did not agree to be interviewed and any contact that could be made would be permissible only through written correspondence, as he is on death row. However, viewers likely will not only be shocked but also infuriated by Wood, who is in a minimum security prison and has been denied parole twice. “Corresponding with Lance [Wood] was very unpleasant,” Anderson says. “He shows very little remorse. Both men took different justice paths. One is on death row and the other is a womanizing prisoner living in minimum security.”

Emanating toxic narcissism, Wood is seen first in 1988 footage after the murder as he leads authorities to the crime scene and describes in detail what happened. Wood, who was raised in a Bountiful LDS family and was an Eagle Scout, apparently was trying to reframe the extent of his involvement in the murder. Even law enforcement authorities were surprised by how much he was revealing but they were convinced that he was an accomplice.

In the film, Wood’s former fiancée compared him to the personality of serial killer Ted Bundy. But, one of the most bizarre moments occurred when he was housed in an Idaho prison. He met Renee Shereen McKenzie, a paralegal and former wife of a Republican state senator, and they eventually were married while he remained in prison. McKenzie is interviewed in the film, and she clearly has no regrets about Wood or her decision to marry him and help his legal cause.

Meanwhile, while Wood’s family refused requests for interviews, Archuleta’s family agreed near the end of the film’s production schedule to be on camera. Anderson had tried for two years to obtain their approval. Unquestionably, the interviews with Archuleta’s mother (Stella) and sister provided the linchpin to tie all of the elements together, as the production team’s overarching concern was to avoid making a film that exploits the memory of Church or sensationalizes the details.

In fact, the themes of love and forgiveness emerge in a subtle elegiac way, as Archuleta’s mother and sister express themselves. Two months after the film was completed, the mother died from cancer.

The interviews are so genuinely emotional in the film, as they reflect the passion with which Anderson has pursued the project. “I felt like I was uniquely equipped for this as a trauma therapist,” he explains, “to sit with people in their pain and professionally carry out these difficult interviews.”

The experience of making Dog Valley has had several levels of impact on Anderson and Lindsay. Anderson recalls the first time he went alone to revisit the crime scene and then drove retracing the path northward to Dog Valley where Church’s body was found and then finally to his gravesite, where his tombstone includes a photo of the young victim. “I was weeping openly and I knew this went from a professional pursuit to a deeply personal project,” he adds.

Complex emotions are integral to the film’s context. Anderson says that he can have compassion for Archuleta while condemning him for carrying out some of the most horrendous acts in killing Church. He has a different opinion about Wood, though, who appears to have had lesser involvement in the murder. Regarding Wood’s apparent lack of remorse and his record of narcissistic, antisocial behavior, Anderson says, “I’m not sure how to feel.”

The final 25 minutes of the film weave through the thematic threads with superb clarity and cohesion. Clips show the 2019 campaign in the Utah State Legislature for enacting a meaningful hate crimes bill, after 28 years of unsuccessful attempts. There also are moments emphasizing the disparities and inequities that many criminal justice reform advocates hope to eliminate, as Archuleta’s legal representation seeks to have him removed from death row and resentenced to life in prison.

Lindsay says that up until this project he always has been a conservative who believes in the death penalty “straight down the line,” adding that his stance has softened after interviewing the Archuletas. “I’m glad I don’t have to make the decision. It’s a tough call for me as a regular guy,” Lindsay explains. “I’m not quite sure where you draw the line.”

Anderson says the experience of telling this story confirms his absolute stance against the death penalty. “In one case, he got death and lost his eye in a weightlifting accident and the other is in minimum security and pursuing relationships with women. Justice was ineffective and horribly administered.”

Finally, the heartbreaking pain for Church’s friends is a grief still acute more than three decades later. His friends cannot reminisce without breaking down in tears. Church would have turned 60 this year but their recollections emphasize that Church always will be youthful in their memories. Anderson says the story and its emotions remind us of “how much the world has changed and how little it has as well.”