Long after their brief time in the public eye has ended, some avant-garde movements exist in remnants that have been absorbed unconsciously into the philosophical and aesthetic bloodstream and reappear with respected significance decades later. In Europe, for barely more than a decade beginning in the late 1950s, the Situationist International movement attracted a great deal of attention for its revolutionary manifestos on visual arts and architecture that ultimately morphed into political and economic activism. But, the movement fell apart after the Paris riots in 1968. In 1963, one of the group’s responses elucidated the reason for its founding: “We have founded our cause on almost nothing: irreducible dissatisfaction and desire with regard to life.”

In Working Hard to Be Useless, a spiritually rich new multimedia exhibition at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA), the remnants of this short-lived avant-garde movement are rejuvenated in works varying in size from standard gallery presentation to impressive monumental scale. The exhibition testifies to the “avant garde of presence” (borrowed from the SI’s own 1963 response to critic Lucien Goldmann who had labeled nihilist artists as working in an “avant garde of absence”) in how artists subvert the prevailing culture, which dictates defensive architecture and the confining boundaries of leisure and pleasure in urban space.

Jared Steffensen, curator, says the impetus for the show came from the scholarly work of Ocean Howell, a professional skateboarder-cum-historian specializing in urban planning, design and architecture. Howell, now in his middle 40s, is a tenured member of the University of Oregon faculty. He is widely sought by international media to comment on matters about defensive architecture and implications of access to public spaces. This includes tactics such as spikes, which discourage homeless citizens, for example, from using those spaces.

His 2001 paper The Poetics of Security is a seminal statement about the formative ideals he has expanded upon in his work. He reminds readers that skateboarders are “not interested in transformational politics” but that the activity “hints at the possibility of a more spontaneous and ‘non-alienated’ experience of the city, but only obliquely. The average skateboarder’s primary concern is that they themselves are able to have that experience.”

The exhibition riffs on the broader theme that compels us to consider why do we, as Howell has noted, feel entitled to “the comfort of a simulated public space, produced by surveillance, directed toward profit, and enforced by spikes and guards.” Steffensen adds that, for some artists, “the Situationist International is a starting point,” but the works also delve into many contemporary issues, which encourage viewers to identify examples of defensive architecture in their own communities and consider the reason why these deterrents are deployed.

From 1992, Toy Amenity, a photo and video demonstration created by Mowry Baden, highlights how urban planners sought to thwart skateboarders by adding deterrents such as skate stoppers, narrow ledges and aesthetically nuanced uses of cobblestone to roughen up surfaces. Baden fashioned a sculpture that includes a concrete ledge with an embedded metal pipe – an obstacle that skateboarders customarily use. Thus, the work inspires skateboarders – and others – to think creatively about overcoming these aspects of defensive architecture that suddenly seem more prevalent if we observe more carefully our own movements in urban spaces. Likewise, the photographic series by Aaron Hegert, visiting assistant professor of photography at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, emphasizes the transitional aspects of confronting and overcoming spaces defined by defensive architecture.

This is accentuated even more so in Nils Norman’s The Urbanomics Archive Trailer (2008), a long-running creative effort, in which the artist highlights just how pervasive these seemingly innocuous elements of defensive architecture are and how they not only target the city’s homeless population, as originally intended, but also restrict use by others in the community, including seniors and persons with disabilities. Alex Villar’s Temporary Occupations video fascinates the viewer, as a man conquers every confined, narrow, defensive space with apparent ease.

Another Norman work (2018) is the large Play Structure, which is inspired by Carl Theodor Sorenson, a Danish architect, who conceived the structure of an ‘Adventure Playground.’ Norman’s work is unlike contemporary playgrounds that are common fixtures at public parks in every community. There are no indicative slides or swings but the structure of ramps, platforms and ladders invites and encourages visitors to play on it. On the exhibition’s opening night, children as well as adults found their own ways to navigate to the top of the structure.

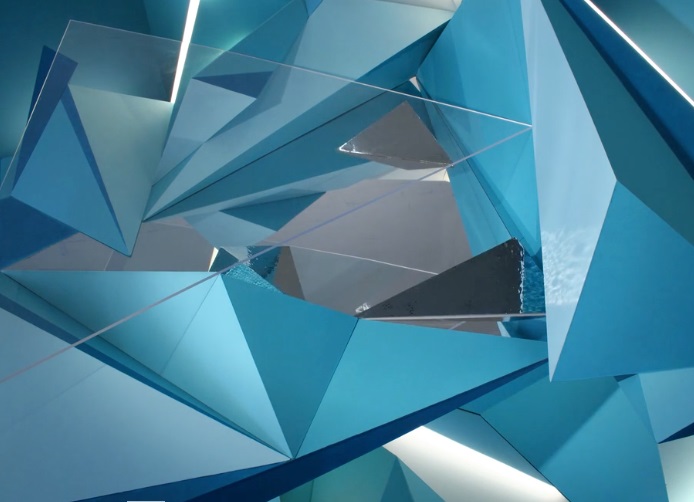

While Norman’s Play Structure stands out in its stark, clean, unadorned appearance, Mark Schatz’s sculpture comprises different visions of the idealized contemporary city, reminiscent of Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), the American futurist who worked extensive in design and architecture. Each component plane of the sculpture is exquisitely detailed and it does remind the viewer of Fuller’s central Dymaxion concept – a portmanteau created from the words of dynamic, maximum and ion.

Some works are whimsical even in their more seriously stated purpose. Archisuits (2005-2006) by Sara Ross are fabric leisure jogging suits that allow the individual to fit into spaces that were designed to not accommodate them. But, once the viewer appreciates the humor (the suits are not all that different from some of the clothing advertised in airline magazines or on late night informercials), one can focus on the question of who is entitled to occupy public spaces and what deems some, particularly the homeless population, to be viewed as trespassers or loiterers.

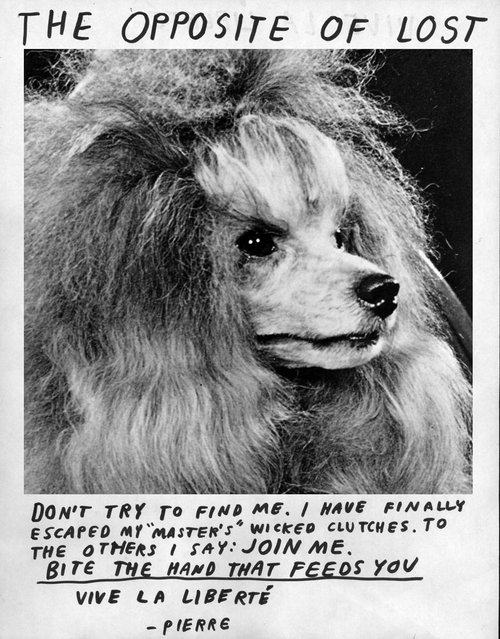

Scattered throughout the exhibition are photocopied fliers with handwritten messages, scanned photos and amateur page layout– part of Nathaniel Russell’s Fake Fliers series. One example inverts the familiar lost dog announcement. It reads ‘The Opposite of Lost’: “Don’t try to find me. I have finally escape my ‘master’s’ wicked clutches. To the others I say: Join me. Bite the hand that feeds you. Viva La Liberte – Pierre.”

Comprising fabric and LED lights, Lynn Richardson’s Inside The Fence (2013) becomes an incisive artistic commentary on the orange-and-white construction barricades that pop up at every urban redevelopment and gentrification project. Richardson’s installation turns these barricades in floating sculptures so there no longer is a functional purpose for restricting movement or admittance to sites previously seen as forbidden to curious onlookers.

Amy Yoes’ work Modification and Collapse is a masterpiece of stop motion animation in a continuously looping digital video. The perspective is set from above looking on an abstracted representation of a city going through endless changes in its architecture and the way is which its residents might travel in the urban space. The video starts with a single form trying to situate itself in a confined space but as the pace gradually accelerates, other objects in different colors compete for tight, narrow spaces. There are many recognizable features common to any city center. The video starts anew once a point is reached that a city cannot sustain any further change in its development.

Many relevant contemporary aspects are represented in the works. In three works from Krista Svalbonas’ Migrator series, the small sculptures built from photographs of large drab apartment buildings emphasize the shifting conception of home, particularly for refugees as well as those displaced by gentrification. Her parents were refugees from Latvia and Lithuania and the sculptures remind of the old practice in Iron Curtain countries where large residential complexes were built in ways to discourage any sustainable, meaningful interaction among the neighbors who lived there. Svalbonas adds other layers that suggest the timeline of how these structures and spaces change.

Likewise, Thuy-Van Vu’s family also were refugees, who left their home in 1975 as the former South Vietnam collapsed and was reunified with its northern counterpart. Her watercolors reference metal playground equipment but as the curator notes indicate, “the complexity of each structure almost negates those notions, replacing them with fear of injury or being trapped within the metal bars. They alternate between inclusion and exclusion making it difficult to reconcile the desire to climb on the bars.”

The exhibition is open until the end of the year. UMOCA also opened a retrospective exhibition commemorating SLUG magazine’s 30th anniversary, which includes the covers of every issue published, along with other memorabilia. The effect is like entering an old style record shop. The overall effect of the covers presented in one setting is compelling to see how the magazine’s graphic design and style evolved over the three decades.

Other new shows that integrate well with the main show include Josh Samson’s The Identity Project. Samson, an independent filmmaker who also has been a UMOCA educator-in-residence, asked a group of emerging young artists about how they approach the task of defining their identity through various artistic media, including film. Among organizational collaborators for Samson’s project have included the Refugee and Immigrant Center at the Asian Association of Utah, Olympus High School’s afterschool program, Leaders and Counselors in Training Program, ArtsBridge and REFUGES. Filmmakers include Brighton Ziegler, Katie Beacom, Lauren Vernon, Keiki Taylor, Casey Josephson and Mikkel Richardson.

Another show that riffs nicely from the Working Hard to Be Useless exhibition is M.A.D. (Mutually Assured Destruction) by Alison Neville, a 2016 graduate of Weber State University’s fine art program, is one of UMOCA’s Artists-in-Residence, a program supported by the George S. and Dolores Dore Eccles Foundation. The exhibit items explore the history of nuclear testing and her sculpture series incorporates information about nuclear test sites in the U.S., Russia and North Korea. It includes a map for each location and a mushroom designating every above-ground, fallout-generating, nuclear weapon test in the history of each program – all built on Cold War-era student desks. The coloring book contains imagery of nuclear weapon detonations that have been colored in with the efforts of children, ages 5-12.

Likewise, Chase Westfall’s Control, a single-channel video work capturing the powerful rhythmic sound of a drum composition by musician Julian Dorio is an instructive complement to the Working Hard to Be Useless show. A founding member of the band The Whigs, Dorio was performing with the band, The Eagles of Death Metal, at the Bataclan Theatre in Paris, France, when it was attacked by ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) militants, leaving 89 dead and many more injured. In contrast to the massively destructive violence experienced in the Bataclan attack, Control presents Dorio’s intensely physical drumming as a constructive and redemptive expression of controlled violence.