With the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) now open to the public in its most expansive offerings in more than a year, the following exhibitions are a must-see during a visit. For more information about hours and the museum, see The Utah Review’s centerpiece article.

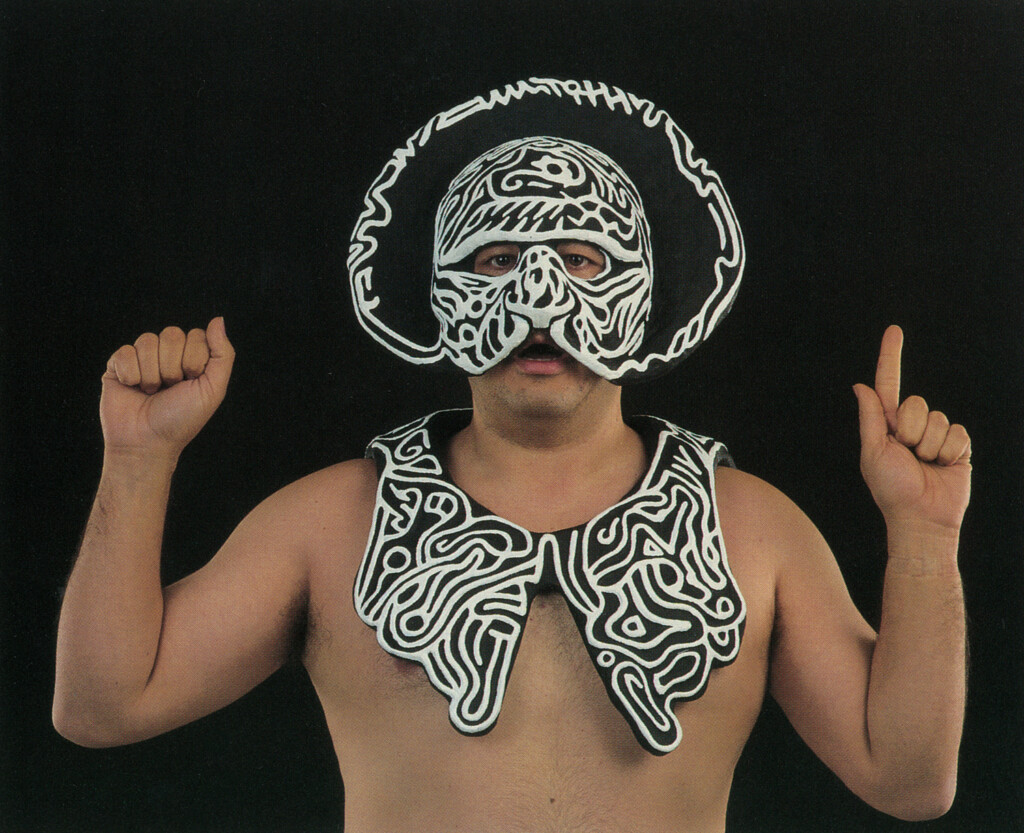

Baggage: Alex Caldiero In Retrospect

Among the Utah Enlightenment’s most quintessential artists, Alex Calderio has demonstrated for more than 50 years the potential to be audacious, experimental and unflinching in artistic entrepreneurship. In his 2018 edition of the Dictionary of the Avant-Garde, author and critic Richard Kostelanetz refers to Caldiero’s own words: “‘The sacred and the secular have been at the very core of my formative years,’ he writes with remarkable clarity. ‘For me this town presence is a pivot between sideshow and temple, between entertainer or jester and priest. In the process of making and presenting a work, this precarious position is the opening by which I can hope to glimpse the Real.’”

Kostelanetz’s words are part of the introduction he wrote for the book, which accompanies the Baggage exhibition at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art. Marvelous for how its transcends the conventions of chronology or linear presentation, Baggage fully realizes what Laura Allred Hurtado, UMOCA executive director, summarizes, again in referring to Caldiero’s own words, “a grand examination of his consciousness.” Thus, the words “retrospect” or “evolution,” while useful to guiding how one might anchor an artist’s process of creative development, do not encompass what this astutely curated exhibition accomplishes. Indeed, as The Sonosopher: Alex Caldiero in Life … in Sound, the 2010 documentary by Torben Bernhard and Travis Low, chronicled, as I wrote at the time: “Caldiero clears away the conventional and stultifying performance barriers between art and the external world, constantly rekindling his relationship with nature, his geographical roots, and his spiritual yearnings. … Poetry accompanied by all its glorious sound is not the escape from reality but a tribute to our individual and collective potential for creative genius.”

Jared Steffensen, UMOCA curator, says that prior to organizing the exhibit, he was not all that familiar with Caldiero’s work, which defies even admirable multidisciplinary attempts to apply genre defining labels. Caldiero has been described variously as a polyartist, poet, wordshaker, scholar, sonosopher and performance artist. Right at first glance, Baggage’s presentation pops with the clarity Kostelanetz has referenced. Caldiero, 72, who is a senior artist in residence at Utah Valley University, has produced voluminously books, chapbooks, notebooks, drawings, monoprints, para objects, recordings, sculptures and assemblages. Just as with John Cage, a composer and artist whose work defied skeptical and even harsh critics to become conceptually and culturally significant to 21st century communities, Baggage also becomes well-deserved vindication for the artist. Incidentally, this is the most extensive show about his work the museum has organized, with various other shows either as solo or with artistic colleagues held over more than the past quarter of a century.

Even in the meticulously selected sample of works that Steffensen and Caldiero decided upon, Caldiero’s creative consciousness shines in its holistic glorifying synthesis of his lifetime experiences. Born in Sicily, raised in Brooklyn and eventually settled in Utah, he embodies all of the experiences, including his own spiritual journey that has traversed Catholicism, Mormonism, mysticism, metaphysics and Eastern spiritual practices. Hurtado writes in her essay for the exhibition book that, for Caldiero, artwork “shows up nearly always parallel to language—and especially when language starts to break down.” Never afraid to make words turn into resonant sounds, symbols, abstractions, or even into babble, Caldiero positions images as a continuation of language, something that forms itself around the in-between breaks and spaces between sound and words.” Intriguing is that one of the rare bits of linear flow in moving through the exhibition is how the images can reverse the effects of language’s “breakdown.” There are the Rorschach manifestations along with works amplifying portmanteau and manipulated words endemic to Caldiero’s creative vocabulary, such as “splace” and “coincycdences.” Viewers instinctively understand what Caldiero seeks to express in response to the inadequacy of language.

Thus, Steffensen has found the most elucidating strands of the emotional content embodied in Calidero’s work. Stepping initially into the exhibition space, the visitor feels comfortable to explore the works on their own terms without the necessity of asking where one should start. Indeed, Baggage includes prints of his 1974 work Monad, one of his earliest published poems, in which the reader can start anywhere and end up with a cohesive, clarifying rendering. Baggage includes many parallel points that resonate with the aesthetic sensation which opened the 2010 documentary about his life. In the film, he proclaims loudly, “I want to go where the sound goes after the bell stops ringing.” If there was a geographical and ancestral starting point to his conceptual life as a sonosopher, it could be the remote caves of The Ear of Dionysus in southeastern Sicily. His creative journey, meanwhile, has followed a similar, ever more gratifying path, right here along the Wasatch Front.

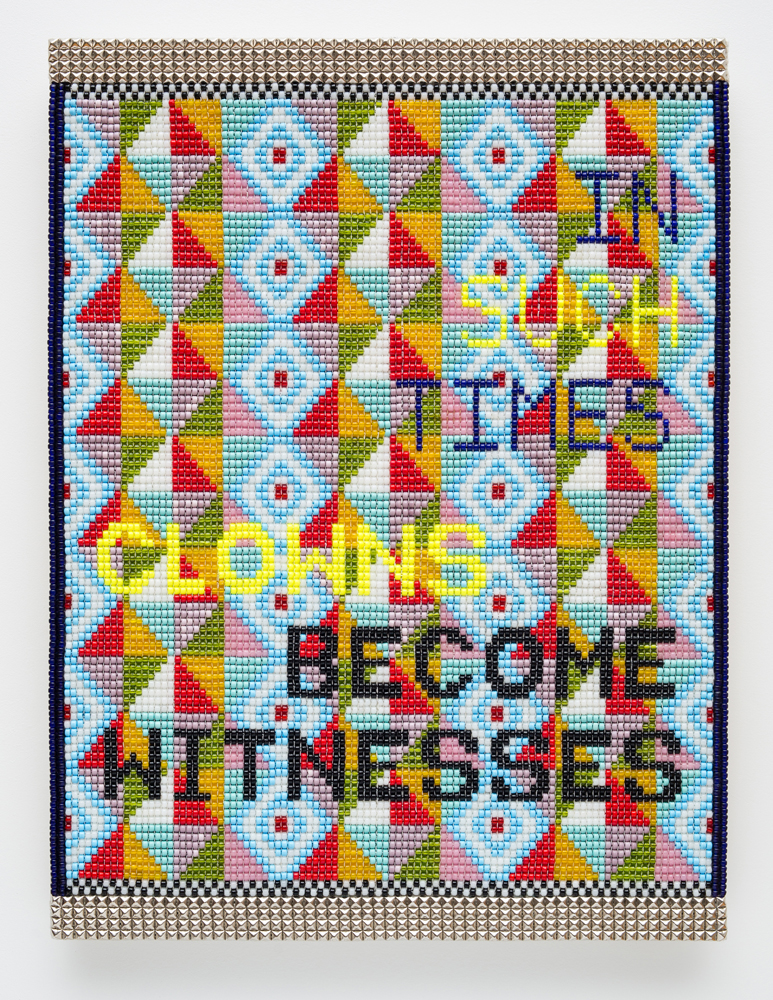

Material Issues: Strategies in 21st Century Craft

UMOCA’s Material Issues exhibition compels a fascinating epiphany about the incompleteness of art history and how we have typically partitioned off folk and hand-crafted art from the historically authoritative spaces of power and aesthetics in the conventional museum setting. In this instance, however, contemporary local and national artists have crafted art, all by hand, that transcends the cultural propaganda of how we frame art history and the untenable distinctions between high and low art.

Again, it is curatorial excellence, which elicits the rich counterpoint of functions and underlying meaning that incontrovertibly validates why these aesthetic and artistic practices should be documented, accepted and displayed in the museum as significant for extending and completing the telling of art history. And, these contemporary examples reiterate why earlier generations of craft-based work belong in the museum on par with painting and sculpture, for example, as making concrete the ideally egalitarian mission of museums.

The versatile presentation of quilts, rugs, ceramics, statuaries, wall objects, etc. evokes awe-worthy delight along with penetrating critiques that set up elucidating paradoxes for the viewer to contemplate. Entering the Main Galley space, the visitor encounters a unique, commanding example of the land acknowledgment practice, with Gina Adam’s quilt about the Spanish Fork Treaty of 1865. This piece is one of a series the artist is creating to portray how the promises of American Indian treaties have been broken. Adams, whose grandfather was Ojibwa and is a descendant of John Adams, the nation’s second president, cuts by hand appliquéd letters from calico and sews them directly onto antique quilts. This particular treaty, as encouraged by Brigham Young, was supposed to assure the Indigenous chiefs of Kenosha, San Pitch and Sow-e-etc a reservation and security in the Uintah Valley in exchange for tribal lands. However, the federal government rejected the treaty six years later, thereby stripping the Indigenous nations of their sovereign identities and claims to negotiate as such. On one side of the quilt, the text is legible but on the reverse side, it is difficult to discern any of the text, a representation of the confusing, bad faith contrivance of a whole body of treaties where few, if any, of the original expectations were fulfilled or were even intended to be honored.

Meanwhile, other exhibition pieces highlight direct connections to Indigenous culture, identity and ceremonial practices. These include two extraordinary examples of ceremonial rugs by masterweaver Elizabeth Clah, an elder in the Dinétah. To truly appreciate the complexity of how these masterpieces are woven, the viewer learns they are created top to bottom, even as they are read from left to right. One honors the benevolent Navajo deity Yéí, in which the tassels of corn stalks are prominent, signifying the spiritual importance of the pollen which is offered in prayer during the ceremony. The other rug shows fire dancers who participate in a five-day winter healing ceremony. Only those weavers who have participated in the ceremony can depict the designs featured in the rugs. To help ensure that the artistic practice can be carried on by younger generations, a Utah organization has connected elders to propagating the techniques and aesthetics of rug making.

Also a member of the Dinétah, Patrick Dean Hubbell has several works, including Primary Star Blanket and Night Sky Protection, which deftly blend abstract expressionism and representation and are folded like Navajo blankets as the art is hung on the gallery wall. Viewers will enjoy comparing the abstractions of patterns and symbols in his work with that of Clah.

There also are larger scale works by Raven Halfmoon, which represent the Caddo tribe. Imposing in their resilience and presence, Halfmoon’s works act as cultural sentries in the exhibition, including Ms. Caddo, a glazed stoneware piece, along with two other stoneware works — We Are Immortal and Ina (Mother).

With utmost melticulousness, Horacio Rodriguez, who also has work featured in the Radicalized Relics exhibit one level above in the museum, makes a momentous statement about the simultaneous commodification, marginalization and exploitation of the people and culture along the southern borders. His wall pieces are based on pre-Columbian artifacts. From the original pieces, which are housed at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, he uses advanced digital scanning, 3-D printing, traditional plaster mold-making, and slip-casting ceramic techniques to create these pieces. He adds bits of contemporary references that literally stun the viewer into thinking anew of the sociopolitical and cultural media dynamics in play. In Brown Boys for 45, the red MAGA (Make American Great Again) hats atop the artifacts he has recreated signify the attempt to understand why some Mexican community members in Houston’s east side could support a politician who unreservedly demonizes Mexicans and immigrants. Meanwhile, in 545, based on a Mesoamerican sculpture that was taken from a burial site, the cage represented carries dual meanings: one about how museums often present such objects without comprehensive cultural contexts but often place it under a pristine display case and the other about the abusive treatment that children who have been separated from their Mexican migrant families have endured at the border.

Likewise, artist Brian Snapp responds to the refugee and migrant issues. In the 2016 piece titled House of My Brother/House of My Sister (Home), the structure appears simultaneously as secure and vulnerable to collapse. Each side presents a stunning contrast of mood and reality that even in their new home, refugees face risks swinging wildly between being welcomed and being threatened. The holes for windows, for example, on one side appear as bullet marks on the other. In the 2020 version, House of My Brother/House of My Sister (Sanctuary for Sorrowful Songs), Snapp mixes yeast into the making of his clay sculptures, an example about how failed materials become the platform for potent artistic effect. The ripping apart of iconic figures brings to mind the violent polarization of the American community and the difficulties of reconciliation.

With Drum Migration 2, Albuquerque artist Ruben Olguin also explores themes about media, cultural appropriation and politics in his work. This assemblage emphasizes the intersection of sound technology and the natural drums, which are made from foraged clay, and are played with sticks made from the yucca plant. While the sound effects are aided by a piezzo disk transducer, amplifier and speakers, one recognizes the drums on their own produce the most ideal aural effects. Another Olguin installation is spectacular in its mesmerizing impact. Traces comprises a trio of micaceous bowls, each situated under a video projection system. The projections represent a continuously changing sequence of images that he gathered from anthropology books and remapped so that they are restored to their true three-dimensional perspective. This is exquisite technique, as the images fit so naturally onto the bowls.

Amanda Smith’s ceramic paintings are astounding in color and detail. At initial glance, they seem to be akin to representations of the Grimm Brothers fairy tales but upon closer inspection they take on a subtle, astute sociopolitical commentary. One is Red State, a work produced during the pandemic, which features a girl wearing a mask trying too fend off threats and horrors in a forest. Smith’s detail is masterly, intricate and smart, accentuated by the marvelous array of textures, luster effects, and other elements afforded by ceramics. They are on par with the rich classic, Arabian and Eastern civilization examples of miniature paintings but they clearly are presented as 21st century pieces.

The exhibition, presented by the Sam and Diane Stewart Family Foundation, also features works by Thomas Campbell, Rachel Farmer, Jeffrey Gibson, Raven Halfmoon, Jann Haworth, Danielle Susi and Rachel Thomander.

Zachary Norman: This Storm Is What We Call Progress

UMOCA’s Artist-in-Residence (AIR) program has led to a consistent string of solid work but Zachary Norman’s video exhibition of seven channels presenting a 360-degree-view of Salt Lake City’s Northwest Quadrant, the proposed site of the controversial Utah Inland Port, sets a high bar for originality. Truly validating the video installation medium as integral to showcasing museum excellence, Norman’s presentation in the AIR Space gallery stands out for its exhaustive research of the intersectionalties at force in the strident debate surrounding the area and the proposed project. This is precisely how a documentary filmmaker would want to frame the underlying currents that push past the political dialogue, which, to date, has done little more than entrench the positions of both sides. Indeed, as Torrey House Press has demonstrated how literature can promulgate the environmental and preservation movements with quicker momentum than conventional political tactics, Norman’s multi-channel installation offers promising guidance as well in encouraging observers to probe what truly animates emotional connections to place, space and environment.

Norman is influenced by the late French documentary filmmaker Chris Marker, who blended still and moving images in unique ways, such as his 1962 time travel art piece La Jetée. Marker’s sensibilities were as much literary as they were about visuals and his work evoked a thorough ethnographic consideration of his subjects. Norman follows suit effectively, bringing in rare archival images and footage to chronicle the habitat and ecosystem of the affected area. He anchors the presentation with a quote from T.S. Eliot’s 1922 poetic masterpiece, The Waste Land. The Eliot reference is significant, as Norman targets how even the bureaucratic Northwest Quadrant label strips the land and water of its natural history and ecological character. As Norman writes, the term “is also ahistorical, as it fails to acknowledge that it has only recently become possible to conceive of the land as a quadrant for development due to the historically low levels of the Great Salt Lake as a result of withdrawals for industrial, agricultural, and economic activities.” Norman’s curation of still and moving images highlights the value of bricolage, a dynamic that certainly has inspired at least three generations of filmmakers who are astutely attuned to the forces of nostalgia, constructed memory and their lasting impact on identity not just of individuals but also of place. Indeed, being inspired to view this controversy through the frame Norman offers opens the path to rethinking just why the Inland Port project should be scrapped.

Kathryn Knudsen: Plume

A wonderful, relevant ancillary exhibit to Material Issues, Kathryn Knudsen’s Plume, set in the Exit Gallery (which soon will become the museum’s second AIR Space), features work crafted from recycled materials, including felt and fabrics. The results are wondrous wall hangings, which connect immediately as portrayals of natural settings. Viewed from a reasonable distance, the works offer images of gardens, ponds, bird feathers, flower petals and even cellular biology. These works are fabric parallels of classic bucolic landscape paintings. Step up close to the work and the skilled use of sewing and layering techniques brings forward how Plume simply had cut, shaped and arranged fabric fragments to create the pieces. Thus, with the layering, Knudsen achieves a satisfying 3-D tactile effect with the works. Furthermore, Knudsen’s works do not have a well-defined edge or ending point — an abstraction of pure delight and respect for nature’s seamless organic cycles.

Allison Schulnik: Mound

For this year, the multimedia Codec Gallery is dedicated to a trio of superb examples of video art animation. Museums and the film industry are embracing the cross-disciplinary value of the short video art piece for their respective merits. For example, in this year’s Sundance, there were several outstanding examples of short films that function as art, notable considering that the final slate of 50 short films came from nearly 10,000 submissions.

The first film is a 2011 work: Mound by Allison Schulnik. Using straightforward stop-motion and claymation, she produces an entrancing five-minute video of a moving painting, crafted from more than 100 figures made from clay, wood and fabric. Set to the 1969 song It’s Raining Today, written by Noel Scott and performed by Scott Walker, the film is utterly delightful. It is a refreshing break from CGI work where, in this instance, one appreciates the full effect of Schulnik’s hands at work. It’s pure surrealism — charming, bittersweet and even melancholic at times. It took eight months to make the video, which telegraphs a palpable ASMR effect.

This summer, UMOCA will present a short film by Japanese video animator Yoriko Mizushiri whose poetic, pastel video images are well known for their sensory delight. Next fall, the gallery will present Erick Oh’s Opera, which is nominated this year for an Academy Award in the best animated short film category. The Korean filmmaker’s film is a masterpiece, which took four years to make and includes the work of nearly three dozen animators who created the 24 sections of the film. Opera is exceptional for its intricate synthesis of every element, which Oh described in an interview as akin to making the perfect clock.

1 thought on “UMOCA’s spring exhibitions include Baggage: Alex Caldiero in Retrospect, Material Issues: Strategies in 21st Century Craft, This Storm Is What We Call Progress”