From his earliest days in California after he arrived in 1903 from Okayama, Japan, Chiura Obata (1885-1975) committed himself to become part of American society. At 18, the young artist even joined an elementary school to work on his English. He studied briefly at the San Francisco Art Institute, realizing that he perhaps could learn more about American art on his own. He joined other Japanese immigrants in founding the Fuji Club, the first Japanese-American baseball team on the U.S. mainland. As Kimi Kodani Hill, his granddaughter recalled at a 2002 lecture, he wrote to his family in Japan, “It is essential to learn American art and its spirit. Therefore, I’d like to free my future brushwork through the means of language study first.”

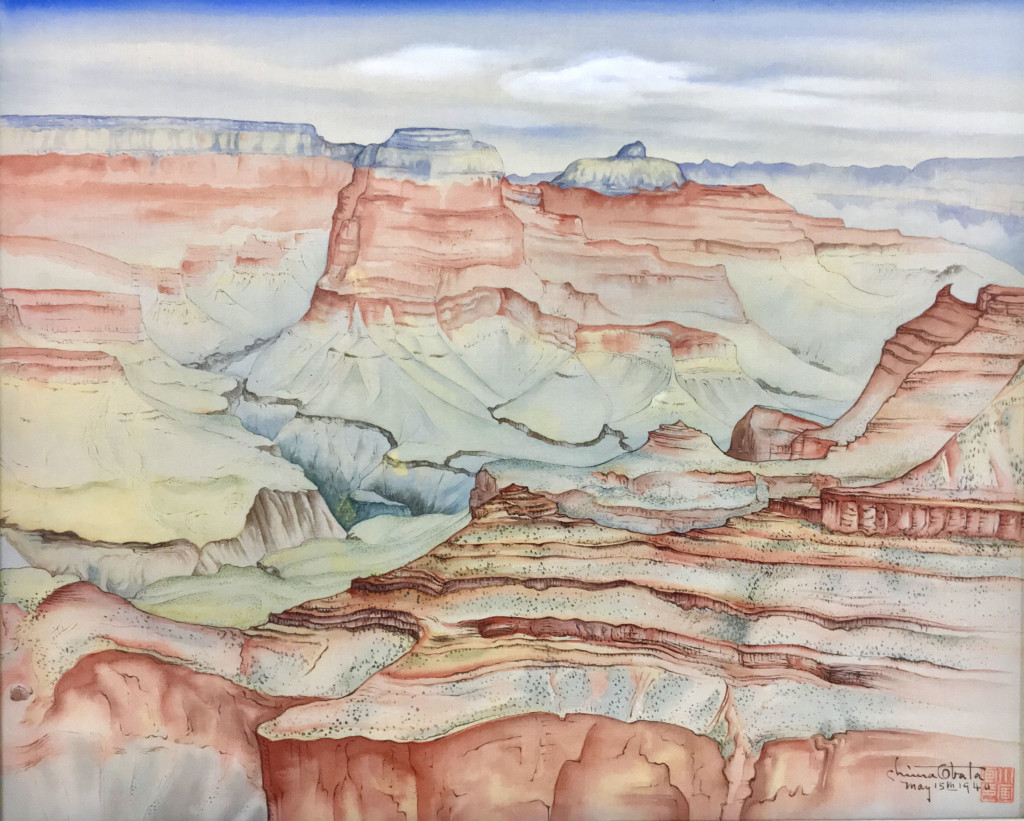

There is a breathtaking revelation in Chiura Obata: An American Modern, the first internationally traveling survey of the artist’s work at the Utah Museum of Fine Art (UMFA). Covering more than 70 years of Obata’s prodigious output, the exhibition features more than 150 watercolors, paintings, prints, and screens, from intimate ikebana (floral arrangements) studies to the majestic landscapes of the American West.

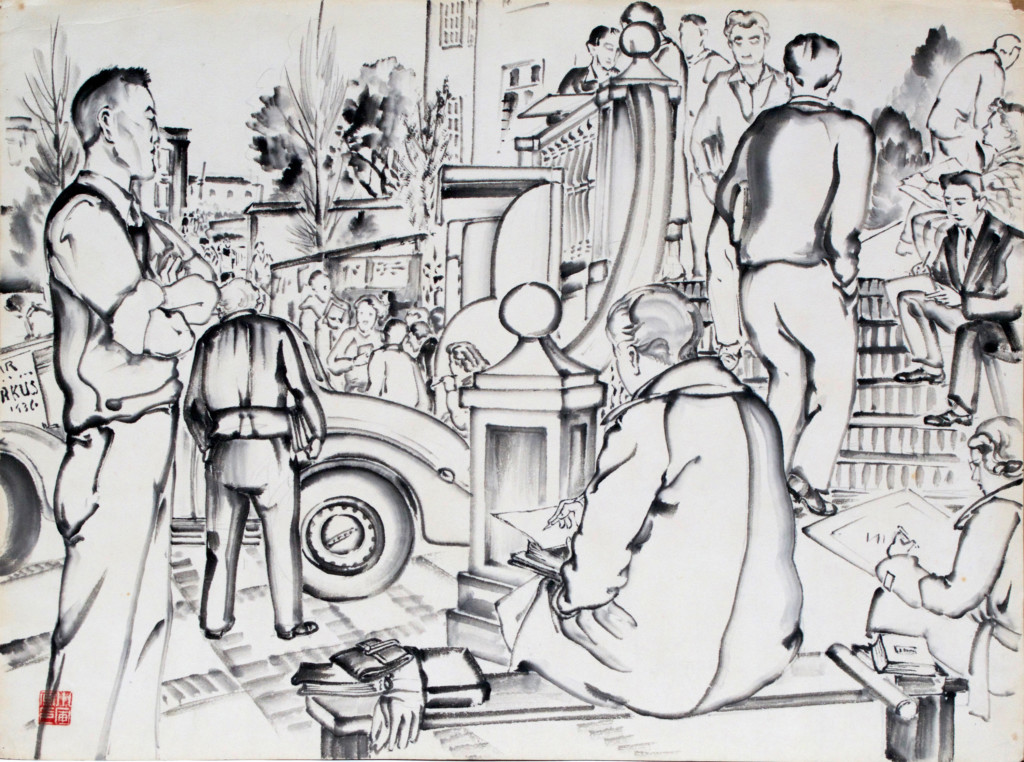

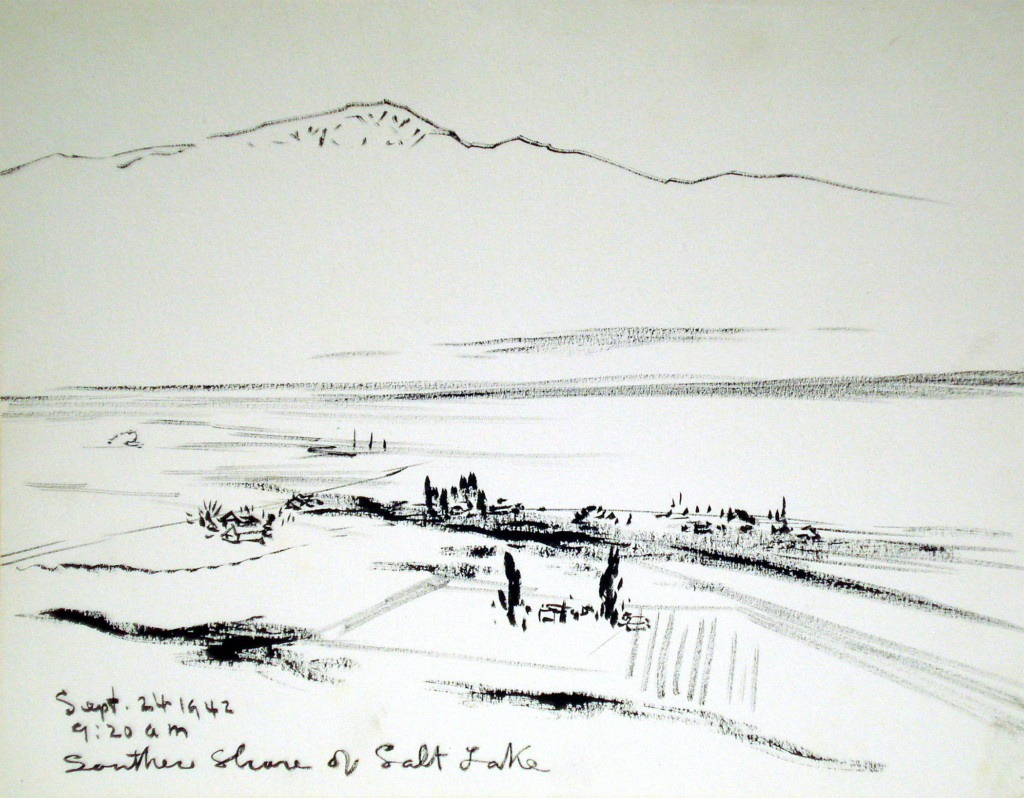

It is a disservice to characterize Obata as a Japanese-American artist. He was quintessentially American in how he captured many iconic moments of the nation’s history – from specifically labeled scenes he sketched after the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco to the college vibe of the University of California-Berkeley campus where he taught art and to the Sierras. But, he also captured another part of American history, beginning April 30, 1942, when the Japanese residents of Berkeley departed for an unknown future in internment camps. Obata and his family were originally housed in the former Tanforan racetrack and horse stables which were converted to barracks. They were moved in the fall of 1942 to Topaz in southern Utah.

At Tanforan and Topaz, Obata never relented in his creativity. ShiPu Wang, exhibition curator and professor of art history and visual culture at the University of California at Merced, says that in 1928, Obata indicated in a letter that he already had created 5,000 works of art, a number that surely grew exponentially, as he worked for at least another four decades. That pace apparently never slowed during the internments at Tanforan and Topaz.

As he continued to produce works, some of which have never been previously shown in public exhibitions until the UMFA show, he also created an art school, which his granddaughter said, echoed his belief in the “power of creativity to raise the spirits of his fellow internees.” Within a month, the school had more than 600 students. Hall, as she recalled in the 2002 lecture, said the school was entirely accomplished with their own funding and from donations of friends at UC-Berkeley.

Obata’s art and life comprise the epitome of resilience, an artistic meta-narrative of the immigrant’s faith in the American experiment that still remarkably supersedes generation after generation of ugly xenophobic and bigoted expressions and actions. Emphasizing the creative impetus for a 1965 work titled Glorious Struggle, a sumi-e Japanese ink painting on silk, Obata recalled the struggles of the Japanese Issei in an interview, especially after the crushing “burst” of Pearl Harbor. “I heard the gentle but strong whisper of the Sequoian gigantean. ‘Hear me, you poor man. I’ve stood here more than 3,700 years in rain, snow, storm, and even mountain fire still keeping my thankful attitude strongly with nature – do not cry, do not spend your time and energy worrying. You have children following. Keep up your unity; come with me.’ So, in the past, all such troubles moved like a cool fog. In deep respect I present my painting to our Nisei and the future generation.”

Chiura Obata (American, b. Japan, 1885–1975), Devastation, 1945, watercolor on paper, 13 x 18 1/2 in., private collection

What is most intriguing is how the exhibition avoids presenting more than seven decades of work in a chronological progression. He consistently used traditional Japanese materials throughout his life but he constantly played with different styles as he made his own studies, focusing on capturing genuine emotional expressions of American life and scenes.

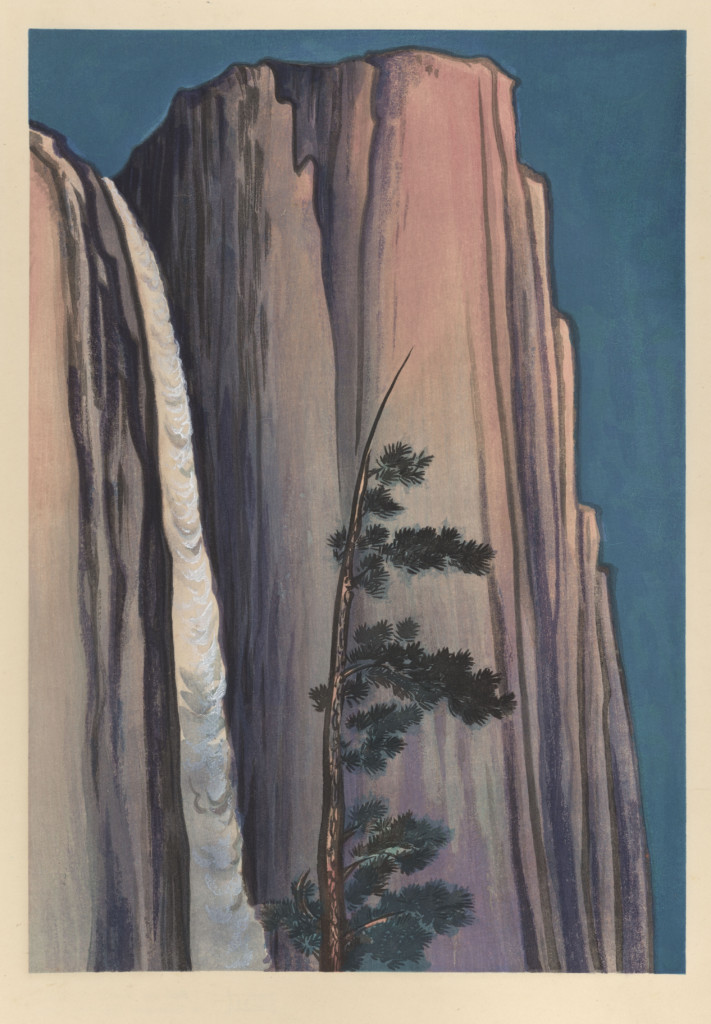

One can see in his earliest works the discipline and rigors of brush stroke technique, starting from the early nihonga style which Japanese artists incorporated Westernized influences. Likewise, there is evidence of tireless practice of technique, ranging from the sumi-e ink paintings to the ink scrolls and the vivid woodblock prints of Yosemite and the Sierras. The works from the postwar period going into the last years of his life synthesize the holistic aspects into a freer, sometimes exuberantly generous expression of the harmony, tranquility and purity that always were critical to his technical execution.

The 1906 miniature but highly detailed sketches of the San Francisco earthquake aftermath are rare examples of the artist reporting directly from the scene. Obata, according to details as told by his granddaughter, was permitted to enter neighborhoods most affected by the quake, after he helped dig a latrine hole in Lafayette Park where survivors had gathered.

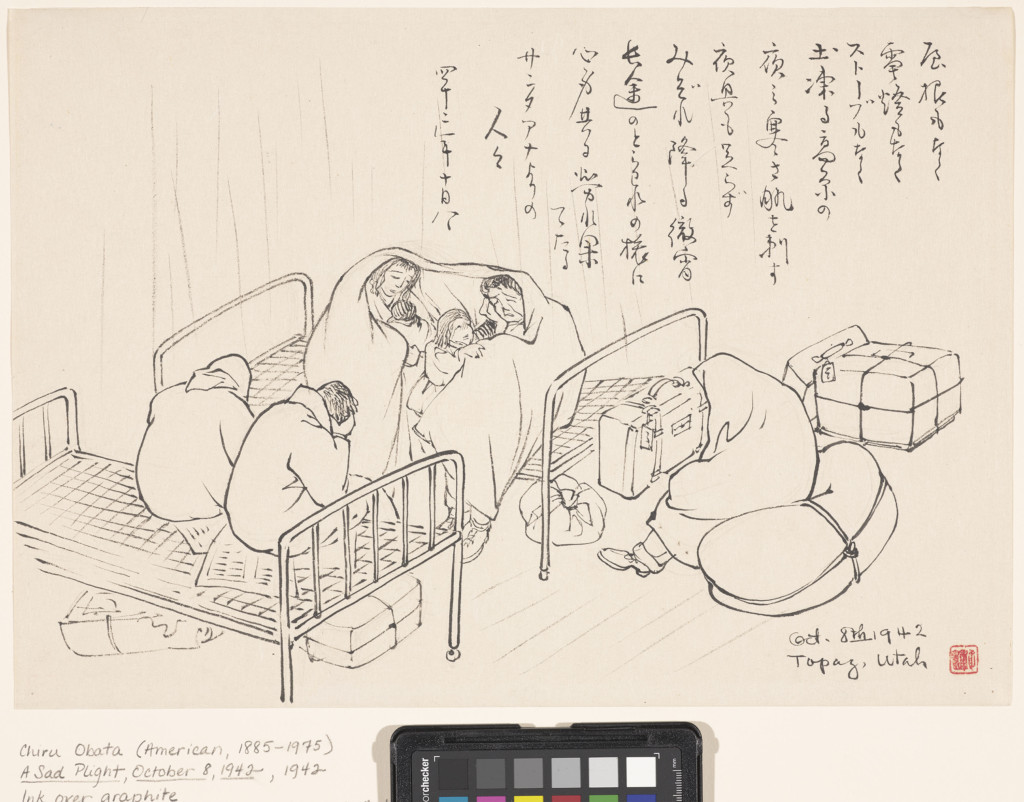

The works from the internment period are tightly drawn but yet the overall terse tone also is telling of the genuine response to this once inconceivable experience. Obata is never overtly political but the details in these pieces convey how conventionally routine activities and scenes take on a disturbing, dehumanizing portrayal.

One example is a scene showing the wearied internees being assigned to housing at Topaz after a long train trip. George Matsusaburo Hibi, an artist who established the camp art school with Obata, described the experience in his oral history, explaining how a dust storm enveloped the area after they had arrived. “The world was covered with grey color, and we felt that we were dumped en masse into a desert where only scorpions and coyotes were living.”

At her 2002 presentation, Hall shared her father’s thoughts when he was 80 in 1965. He talked about America’s “natural blessings” and the dangers of disobeying nature. It is perhaps the best advice for how one might approach absorbing the incredible, eye-popping depth of this new exhibition:

The great teaching of our Japanese ancestors is do not disobey nature, always go with nature anywhere in any circumstance with gratitude. In the High Sierras in the evening it gets very cold. The coyotes howl in the distance. The moon arcs across the sky. The trees are standing here and there and it is very quiet. You can learn from the teachings within this quietness. Well, you can learn from many things. Some people are taught by speeches or talking but I think it is important that you are taught by silence. Immerse yourself in nature, listen to what nature has to tell you in its quietness so that you can learn and grow.

Utah is the second stop for this new exhibition of Obata’s work. Three years ago, Obata’s work was featured prominently in When Words Weren’t Enough: Works on Paper from Topaz, 1942–1945, the inaugural exhibition for the Topaz Museum in Delta. His art also is in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and other institutions.

Working with Wang, who examined more than 800 works of the artist to select the more than 150 featured, Luke Kelly, UMFA associate curator of collections and antiquities, organized the exhibition for Salt Lake City.

After the show closes Sept. 2 at the UMFA, it will travel to Obata’s hometown in early 2019 at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art. Later destinations include the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

The Obata exhibition is included as part of UMFA’s general admission. Among the supporters for the exhibition are the Terra Foundation for American Art, with Dr. and Mrs. James Ferguson serving as Utah presenting sponsors.

Hall and other descendants of Japanese-American internees from Topaz will give a free presentation Thursday, May 31, at 6:30 p.m. in the UMFA’s Katherine W. and Ezekiel R. Dumke Jr. Auditorium.

The UMFA also has scheduled adult open studio sessions for sumi-e ink painting on June 6 and Aug. 1, 6-8 p.m., and June 6, 1-4 p.m. for the Third Saturday for Families program.

UMFA also has scheduled an excursion to Delta, Utah, including stops at the Topaz Museum and the site of the internment camp, on June 30, beginning at 8 a.m. Other events, including a gallery talk, will be announced at a later time.

The exhibition catalogue, published by the University of California Press and available in the UMFA Museum Store, includes images, scholarly essays, and a selection of Obata’s writings, including a rare 1965 interview with the artist. Visitors also may download an Apple-compatible app Digital Obata to augment the exhibition experience.

For more information, see the UMFA website.

1 thought on “UMFA’s Chiura Obata: An American Modern exhibition – an artistic meta-narrative of immigrant’s faith in American experiment”