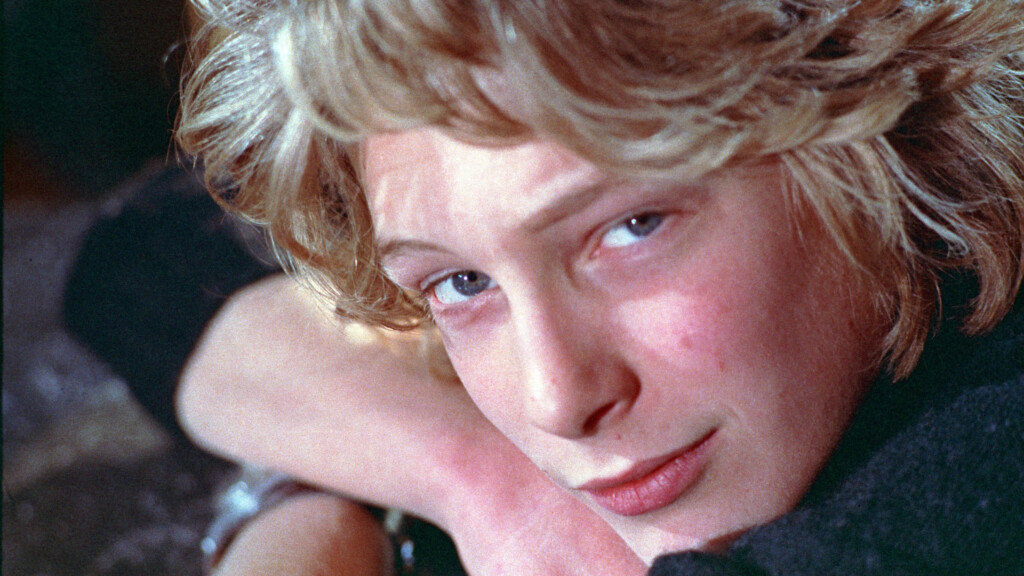

For his novel Death in Venice, Thomas Mann’s visualization of Tadzio, the strikingly beautiful boy, was based in part on Boy with Thorn, an ancient Hellenistic bronze sculpture of a boy who was pulling a thorn from the sole of his foot. In 1970, when Björn Andrésen, who was just 15, was cast as Tadzio in Luchino Visconti’s film adaptation of the Mann story, Margareta Krantz, the Swedish casting director for the film, grasped the gravity of the risks involved. She said, “The boy was exquisitely beautiful. He is fragile. And that is beautiful… on film. You have to be very careful with such children.” Visconti, dedicated to adapting Mann’s novel with as much fidelity as possible, had traveled to numerous cities in the hopes of finding a boy who matched Mann’s description of Tadzio in the text.

Andrésen’s film debut sparked a brief, intense spurt of global fame. In Japan, he drew large crowds and recorded pop songs. However, only a few knew how to appropriate sensitively the visual impact of Andrésen’s appearance. For example, he inspired Japanese shōjo manga artist Riyoko Ikeda to create the androgynous main characters for her legendary series The Window of Orpheus and The Rose of Versailles.

In 2003, when Germaine Greer used his boyhood photo as the cover for her coffee-table book of erotica and history titled The Boy, Andrésen was infuriated by the irony that one of the contemporary era’s best known feminists was appropriating his image as an object of desire when a large part of the feminist movement was constructed to critique the notion of objectification. In an interview with The Guardian at the time, he said, “I have a feeling of being utilized that is close to distasteful.”

In their wholly absorbing, intricate, sensitive documentary The Most Beautiful Boy in the World, which is receiving its premiere at Sundance this year, Swedish directors Kristina Lindström and Kristian Petri bring Andrésen’s story to the present, as an individual, now in his middle 60s, who commits himself to finding sincere love and self-respect for the first time in his life.

In the film, Andrésen is about to be evicted from his apartment because of filth and his carelessness with leaving gas burners on. He has a girlfriend who truly cares for him but she also is so exasperated at times that she periodically threatens to break off the relationship. Yet, she inevitably returns to him. His family life always had been difficult. His father was missing in his life, as he had died when Andrésen was very young. His mother was a vagabond of sorts who enjoyed the company of artists. In the film, the details of his mother’s death are revealed and audio excerpts from a secret vinyl recording with messages and poems read by his mother.

Meanwhile, it was his grandmother who urged him to answer the casting call for Tadzio and then make the trips to Japan and European capitals after the film captured international audiences. His grandmother enjoyed the trappings of celebrity and seemed more than willing to indulge such desires without considering the emotional damage it had wreaked on her grandson. In the 1980s, his son died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and Andrésen divorced his life. A talented musician, he always had hoped to make a career of it. He also continued to act, playing, for example, an old man in the 2019 folk horror film Midsommar.

The film took five years to complete and it is evident that the directors proceeded carefully in allowing Andrésen to determine when he was comfortable enough to recall the experiences along with the sacrifices, disappointments and pains that accompanied them. The directors do a magnificent job in presenting Andrésen’s story, acknowledging how their subject had felt pained emotionally by being used in his younger days, as he mentioned in the 2003 Guardian interview, “like an exotic animal in a cage.”

“We recognized that Björn’s story was larger than life but we wanted to be about him, not Tadzio,” Lindström says in a phone interview from Sweden with The Utah Review. “We waited for him to open the doors bit by bit.” Likewise, Petri, the film’s co-director who joined the phone interview, says, “He knew what we wanted to talk about it and he invited us in and we waited for him, almost just like the film Interview with the Vampire [1994]. It was crucial to develop the trust and we did not put any pressure on him, knowing that when he was ready for it, he would let us know,” Petri adds.

For example, it was two years into the project before Andrésen invited the production to his home. “We were fortunate that the producers gave us the time and space so we could wait to get into the next room,” Lindström explains.

This is a marvelous documentary with a cinematic narrative aesthetic. While the directors weave in some remarkable archival footage from the casting and the production of the film, the most significant elements come from the footage and recordings of Andrésen. Bit by bit, the directors discovered a large trove of documented family memories, going back to Andrésen’s earliest days of his life. And, of course, as he stepped into the limelight as a teen, his aunt and grandmother documented the activities and travels.

The most striking and disturbing footage from the early 1970s is from a press conferences at Cannes, the destination following Death in Venice’s world premiere in London. The directors discovered this footage in television archives in Rome, which had not been seen in 50 years.

Andrésen was just 16 at the time and the Italian director Visconti is ribbing his young star who appears confused at why the press are laughing so hard at a comment the director made. Speaking in French, Visconti told the reporters that the boy is no longer the most beautiful boy in the world. Andrésen did not speak French. One can easily understand why the brutal sting of Visconti’s jest would not diminish in its intensity after so many years.

There also are moments when Andrésen retraces some of the locations of those teen years, including the Lido hotel where Death in Venice is shot. He seems the happiest in his return to Japan, including a meeting with Ikeda and others who had worked with him as a teen movie and music idol. “When he went to Japan, he now had the chance to relive it again as an adult,” Lindström says. “We were thrilled to find all of these people that he had met and they had strong, genuine memories of him. They really cared for him.”

The directors rightly place the Tadzio story in an understated context that allows the viewers to experience and process the experiences in their own way. The notion of casting a newfound young actor in a story of the emotional gravity and complexities of Death in Venice was fraught with bringing on the risks of lifetime consequences and emotional scars. Mann (who nevertheless struggled with accepting his own sexual identity, as his diaries and letters indicated) appeared more intent on framing the story within the tropes of classical myth than as homoeroticism, which clearly became the intentions of Visconti’s interpretation. The character of Tadzio was Narcissus and Aschenbach, the composer character in the story, of course, envies the boy because of his own repressed impulsiveness. It became a multi-layered tale of Freudian paradox and irony.

Meanwhile, the directors in this new documentary succeed in creating a portrait that allows Andrésen to reclaim his story on his own terms. There are many instances where the revelations are candid and as realistic as they ever could appear, perhaps due in part to his own instincts as an actor who knew how to be comfortable in front of a camera. It is a story of reconciliation and resilience. He anticipates optimistically his ongoing work as a musician (in fact, two new songs are expected to be released in the near future). And, he is renewing the significance in his relationships, including his girlfriend and adult daughter.

For information about tickets and the entire festival program, see the Sundance festival website.