A Mormon-themed dark comedy narrative and a Turkish sociological thriller surrounding two university students underscore just how rigorously curated this year’s Sundance short film program is. Gregory Barnes’ The Touch of the Master’s Hand and Serhat Karaaslan’s The Criminals are among this year’s 50 short films which were selected from 9,933 submissions.

The Touch of The Master’s Hand is an absolute gem by Barnes, a queer filmmaker and alumnus of Brigham Young University who is now pursuing his master’s degree at the New York University Tisch School of the Arts. The main character in this short, which runs just shy of 12 minutes, is Elder Hyde, who is serving his Mormon mission in Mexico. He struggles with deciding whether or not he can overcome his shame and confess his addiction to pornography during his worthiness interview with the mission president. The object of his addiction rightly caps the impact of the absurd humor.

Barnes, who served a mission in northern Argentina, sets the dialogue of the interview with the mission president that exudes a familiarity that will resonate with Mormons while not burdening it with insider material that otherwise would prevent non-Mormons from enjoying the full absurd humor that carries the scene. The actors — Samuel Sylvester as Hyde and Samuel Whitehill as President Packard — succeed in the difficult task of making their characters believable while pulling off the humor with smart nonverbal cues and gestures in perfect deadpan effect. Likewise, the dialogue is spoken in Spanish. No easy task for the actors to make convincing portraits but the results are impressive: Sylvester, a Vassar College alumnus, is Jewish and a polyglot, while Whitehill, a retired attorney from Texas who is now a professional actor, was raised Catholic and speaks impeccable Spanish.

In an interview with The Utah Review, Barnes, who was raised in a Mormon family in Illinois, says that while the film is not particularly autobiographical, it does reflect the anxieties and tensions of growing up in a church where belonging to it demanded aspiring to rigid norms of masculinity and acknowledging that pornography was the gateway to plagues of sin. “In high school, I masturbated all of the time but I was constantly terrified about it because my father was bishop of the ward,” he recalls. “When I went on my mission, I did not masturbate once and I didn’t have to lie about it.”

His family has long roots in Mormonism, going back to his great-great-great-great grandmother in New York who met Joseph Smith in 1834. The story was filmed in a Mormon church built by his great-grandfather.

“Basically, I wanted to build the film around a simple dialogue,” Barnes, who no longer is a member of the church, says. He adds, “I wanted to lift the veil to show what the missionary experience was like,” which includes scenes of charmingly naive team-building activities during a mission conference. Fidel Ruiz Healy’s cinematography enhances the excellent production values of this short.

The acceptance of Barnes’ Mormon-themed narrative in Sundance is significant considering that most stories about Mormonism in recent years have been told as sociopolitical controversies in documentaries that have premiered at the festival. As a narrative, Barnes’ film succeeds because it allows Mormons to embrace in good nature the quirks and absurdities of their faith.

The late playwright Eric Samuelsen, who was a major figure in Utah theater and Mormon literature, said that the film comedy Napoleon Dynamite (which, incidentally, premiered at Sundance) was “the one genuine crossover hit of the entire Mormon film movement.” Noting that it was made by a Mormon film director, starred a Mormon actor and its story echoes life in a mainly Mormon community, Samuelsen explained that “its outlook and approach are more directly informed by a thoughtful examination of Mormon culture than even the HaleStorm comedies.”

Samuelsen put it well: “For an independent film to succeed, the film itself has to be the star. Audience members have to be attracted to that film, usually because they have heard about it, heard that it is offbeat, unusual, that its story is not structured the way most traditional Hollywood narratives are structured, or because it is amusing or provocative in ways standard Hollywood films often are not. This is precisely the case with Napoleon Dynamite.” The Touch of the Master’s Hand meets these requirements handily in a story with the appropriate happy ending.

When asked about how people close to him had reacted to the film, Barnes says, “My mom, a devout Mormon, was so happy to see that Elder Hyde made the right decision.” He is working on expanding the short into a feature-length film.

Barnes’ film and Karaaslan’s short round out seven films being screened in Sundance’s Shorts Program 4. The Criminals, set in northern Anatolia, starts out on a simple premise: two university students decide to find a hotel room for a romantic encounter but their quest turns out to be a night of hell and fear. They cannot register for a room together unless they can produce proof of being married. They decide to register separate rooms but the hotelier holds onto their IDs, as a warning that if they violate the rules, there will be trouble.

Elsewhere, the basic premise might end up in a rom-com story with a few madcap antics as the couple find ways to break the rules and enjoy the evening together. But, Karaaslan’s film, which bristles with solid performances by every cast member, emerges as an alarming statement of what Turkish society is becoming for young people. Turkey, a constitutionally secular republic for the last century, has become increasingly more socially conservative and religious with strict Islamic codes of conduct being enforced. The Criminals qualifies as one of the most highly recommended short films in this year’s Sundance slate.

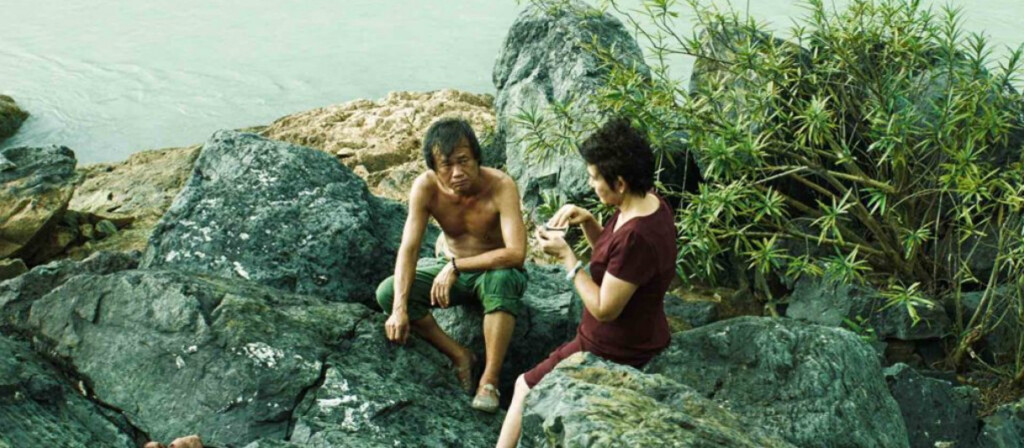

The other films include Annie St-Pierre’s Like the Ones I Used to Know, an acutely accurate short narrative which takes place during a Christmas Eve family gathering, as a father wrestles with the uneasiness of stepping into his former in-laws’ home to pick up his children. Meanwhile, absurdism also propels You Wouldn’t Understand by Trish Harnetiaux about a stranger who interrupts the idyllic vibe of a man enjoying the luxuries of a solo picnic. As a video art and poetry piece, I Ran from It and Was Still in It, by Daryl Olu Kae, reflects on the counterpoint of unconditional love against the emotional pains of loss and separation from family. Hazel McKibbin’s Doublespeak captures the realistic aftermath for a woman who has reported incidents of sexual harassment in the workplace. From Vietnam, The Unseen River, by Phạm Ngọc Lân, offers an elegant parallel in two stories. One is about a woman who reunites with an ex-lover on the banks near a hydroelectric plant as both individuals recognize the coincidences of fate that have brought them together again and the other is about a young man who goes to a temple in the hopes of overcoming persistent insomnia.

For more information about this program, tickets and the entire festival slate, see the Sundance website.

I enjoyed your review–but some minor corrections. I don’t know if Sam Sylvester is Jewish or not. But I am (I was NOT raised Catholic)–my Spanish is good, but not impeccable –yours truly Samuel Whitehill http://imdb.me/samuelwhitehill