In the U.S., the art of dance has been a revolutionary art form. Dance artists and choreographers have expanded the possibilities of movement languages and their own distinctive vocabularies to produce work that often speaks to the urgency of the contemporary dynamics socially, politically and culturally through magnificent storytelling without the necessity of text.

It was only in the second half of the 20th century when the premise of a dance company being able to thrive and continue was realized. In Salt Lake City, for example, there are two institutions – Repertory Dance Theatre (RDT) (55 years) and the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company (57 years). At the time when RDT was founded with a Rockefeller Foundation grant, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater was the only major U.S. company that would include repertoire works by other choreographers.

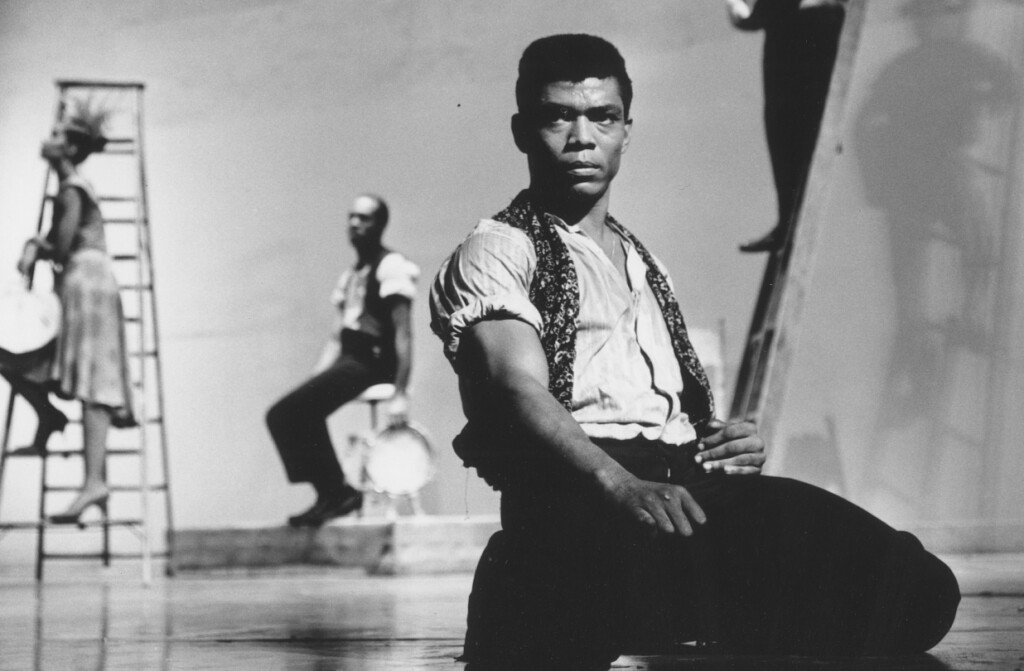

In 1958, then 27, Alvin Ailey founded his company which would carry his name with the American Dance Theater appendage. In 1960, he premiered the work of Revelations, which, perhaps, as a work of modern dance, has been seen by as many people who have watched a performance of a classic ballet on the order of Swan Lake.

Ailey’s artistic legacy is expounded upon elegantly in the eponymously titled documentary, directed by Jamila Wignot, which is receiving its premiere at this year’s Sundance.

Wignot and her team produce a richly sourced historical perspective on Ailey’s artistry. With Rebecca Kent, archival producer, and Annukka Lilja, editor, Wignot highlights original performances of some of Ailey’s best-known works including Revelations. Clips also feature the great artists who performed with the company including Carmen de Lavallade as well as Judith Jamison, who became the company’s artistic director after Ailey died in 1989 from complications related to AIDS.

Both artists also are interviewed along with others who were integral to the company and to Ailey as fellow artists including George Faison, Masazumi Chaya and Bill T. Jones. It has been more than 30 years since Ailey died, but these interviews demonstrate just how profound their connection with Ailey was and the clarity of those memories today.

“As I am a documentary filmmaker and not an expert in dance, I experienced a huge learning curve in making the film,” Wignot says in an interview with The Utah Review. “I still remember watching an Ailey company performance for the first time in college, which also was my first big exposure to dance.”

Viewers will note that the film opens with the actor Cicely Tyson, an icon in her own right who just died a few days ago at the age of 96, introducing Ailey in 1988 just before he was presented the Kennedy Center Honor for Lifetime Contribution to American Culture. Tyson called him the “Pied Piper of modern dance.” That same scene pops up at the end, focusing on President Reagan, putting the tacit but deserved condemnation of a president who refused to act on stemming the crisis of the disease that was responsible for Ailey’s death. In 2014, President Obama awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civic honor in the U.S., to Ailey as a posthumous honor. Robert Battle, the company’s director, accepted the award.

There is no question that the people Wignot featured in her film honored fully his vision, willing to step in as needed to ensure the company would be sustained. The most significant finds in archival material came from audio recordings with Ailey, made during the final year of his life. In the recordings, Ailey recounts his life, which started in extreme poverty in Texas; the disparate and diverse sources of his artistic inspiration, and his personal discovery of his gay identity. His life was filled with many personal crises. Nevertheless, as with so many artists who sacrifice their own well-being to keep the flame of their vision going, Ailey remains an individual whose biography is filled with not fully understood complexities.

“I realized that I could not use a traditional narrative way to capture the emotional arc of his art,” Wignot says. “There are so many expressive possibilities in understanding how an individual who was so private could unleash so much on the stage. He gave all of himself on the stage and dance allowed him to speak of all the things that he couldn’t in his private life.”

The film also features rehearsal scenes from 2018, as Rennie Harris, a Philadelphia choreographer known for hip-hop dance artistry, set a 60th anniversary commission piece celebrating the company. Harris was tapped as an artist-in-residence by Battle, the current artistic director of the Ailey company. “To chronicle the making of a dance, I had to raise the bar for myself yet one more time,” Wignot explains. “I had to immerse myself in understanding the language surrounding that art form.”

Harris’ two-act evening-length work, Lazarus, premiered in late 2018 to unanimous raves. For example, in The New York Times review, Brian Seibert noted how the work incorporated the concerns about “blood memory” and the challenges of being “a Black man in a white world.” Referencing the “rhythmically intricate footwork” of the GQ Philadelphia style inherent in Harris’ movement language, Seibert concludes that “Lazarus brings Ailey back to life by showing why he still matters to a living artist of Mr. Harris’s caliber.”

Wignot’s film underscores this point with equal emphasis. The takeaway from Harris’s Lazarus is renewed by Jamison’s comment near the end of the film that the last breath of her beloved colleague was a deep inhale and more than three decades later, the company continues to thrive on the exhale response.

Made as a PBS American Masters series documentary, the film has been picked up by Dogwoof for international distribution rights outside of the U.S. Ailey is one of three documentaries premiering at Sundance this year that received a fiscal sponsorship from the Utah Film Center. Geralyn Dreyfous, the center’s cofounder, also was executive producer through Impact Partners for the film.

For more information about festival tickets and film, see the Sundance website.