Sicily is the ancient cradle of toxic masculinity and unconditional violence. The Mafia—the Cosa Nostra – signifies power in its utmost pathological form. For many Americans, The Godfather film trilogy has codified a particular frame of reference when it comes to discussing the Mafia. In an interview before his death in 1999, Mario Puzo admitted that the honorific of “the godfather” was a romanticized invention, as he had sought to find an Italian—American parallel to the mythologized image of the American cowboy. Francis Ford Coppola, in a 2003 interview with Cigar Aficionado magazine, similarly confessed that he knew nothing about Italian criminals. He added that the characters were based on “my Italian relatives, who, of course, were not criminals.”

In the early 1970s, at the age of 36, following her divorce after nearly 20 years of marriage and raising three daughters, Letizia Battaglia became a journalist and soon took up photography, believing that the images she took would help sell her work. Born in Palermo in the middle 1930s, she had returned to her hometown in the middle 1970s after some time in Milan. With her partner and fellow photojournalist Franco Zecchin, she went to work for the former L’Ora newspaper, which espoused leftist causes.

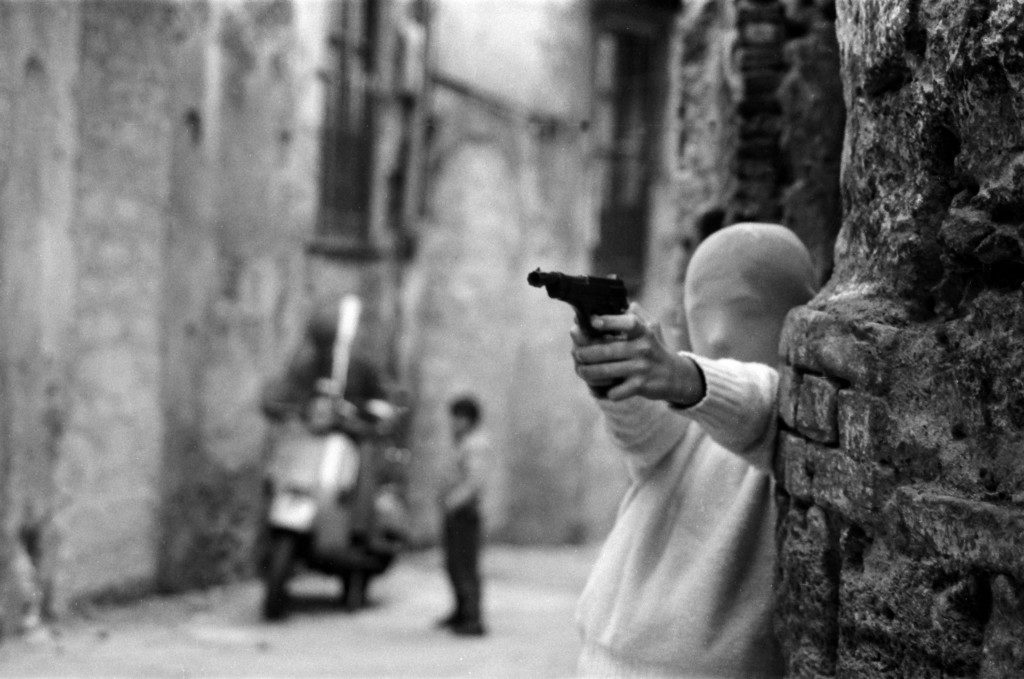

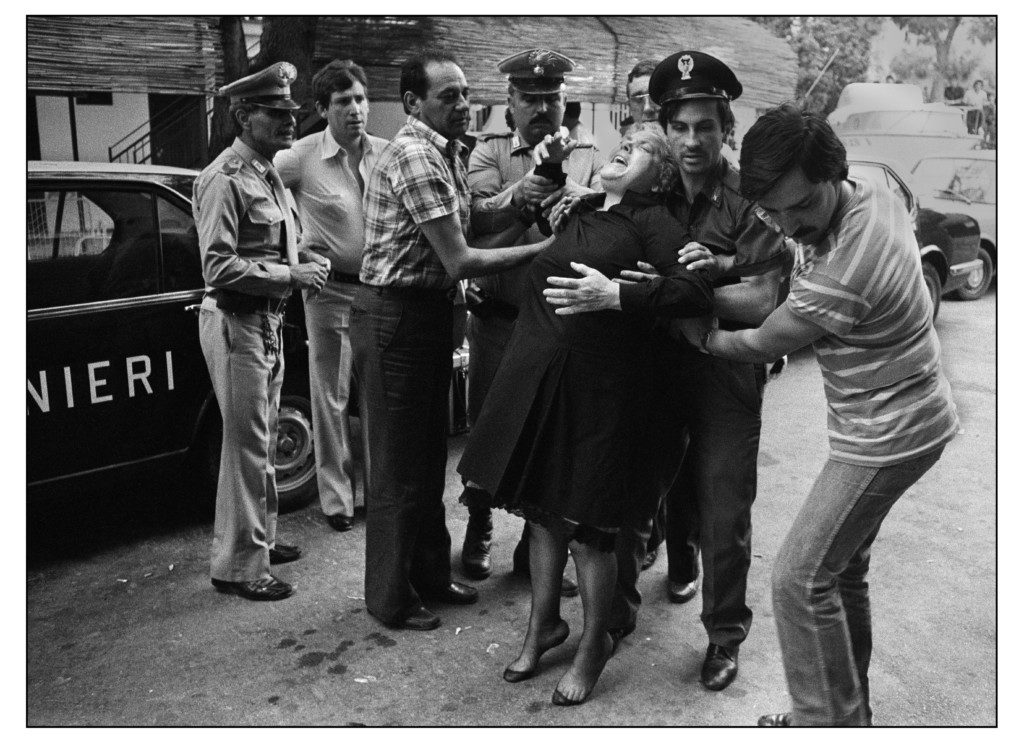

During more than three decades, she took approximately 600,000 images – documenting the Mafia’s relentless assault in Sicily. Her work, which she described as an “archive of blood,” appeared on the newspaper’s front page virtually every day. Unlike many American newspapers, where editors struggle with the ethics or the risk of offending its readers with images that barely capture the magnitude of such brutal violence, Battaglia’s photos became incontrovertible and damning evidence of just how grave this pathology of power had become.

In her own voice, stronger and more resilient than ever at the age of 84, Battaglia stands front and center in Shooting the Mafia, one of the world documentaries premiering at Sundance this year. Kim Longinotto, an award-winning director whose works feature the uncompromising risks women around the world have taken to confront violence and injustice, creates a dynamic portrait that succeeds brilliantly for its finely curated and edited elements of rare archival footage including clips from RAI, the Italian national broadcasting company, old Italian films, and home movies. And, of course, there are stills from the enormous archives of Battaglia’s work. These additional elements situate and amplify the rich layers of thematic epiphanies, which define Battaglia’s life story and work. Longinotto won the World Cinema Documentary Directing Award for Dreamcatcher at Sundance in 2015.

There are many unforgettable moments. In one scene, Battaglia recalls the arrest of Salvatore Riina, considered the boss of bosses in the Mafia. Riina had ordered the car bombing that killed Giovanni Falcone, the anti-mafia judge, a figure whom Battaglia revered for his fearlessness in investigating crimes, as opposed to many Italian public officials who either feared retaliation or were themselves incriminated in corruption associated with the Mafia. Riina, who was born in the village of Corleone (the same one forever captured in The Godfather story), was nicknamed the Beast. Two months later, he ordered the assassination of another judge, Paolo Borsellino.

Battaglia recalls that in his first appearance, he looked like a “shabby moron.” Riina (who died in 2017) told the court that he is “a poor illiterate” — “just a poor farmer” – and that he was not the person the authorities thought him to be and nobody had said anything to him or had stopped him for so many years.

The claim obviously is so absurd to give it any credence. Equally incredulous is the explanation by another Mafia figure who rationalizes why he has people killed. He gripes about them bothering him, distracting him from his daily routines. He sees his victims as inferiors who deserve to be killed. There are images of the disheveled, trash-strewn living quarters where Mafia bosses live and hide for many years. Battaglia says that one would think that they would want to live ostentatiously because of their wealth, but all they care about is unrepentant power in its worst form.

Many of Battaglia’s most imposing images capture the impact of indiscriminate violence on innocent victims and their loved ones, engulfed in inconsolable grief. What will shock some viewers is contrary to the presumption that the Mafia’s ordered hits were executed with surgical precision to avoid killing others in the attack. The unsettling truth is that the Mafia did not think twice about killing children or women. Battaglia explains how some images that she took were so gruesome, especially those with children, that she could not bear to have them published in the newspaper. So extensive was her work that, in some instances, she had forgotten that she had taken some of the photographs.

There is the rightful scorn sensed when she scoffs at the pretense of these Mafia men as noble individuals mindful and sensitive to the image of family. When Riina’s son was 17, the elder ordered him to strangle a businessman who had been kidnapped in the Sicilian countryside – the ominous initiation into the Cosa Nostra.

Battaglia is a complex, even difficult, woman who defied the conventions of her native Palermo in many ways. The archival clips from films and other sources round out the context of what Sicily was like, for example, where men did not hesitate to hit or assault women in public. Battaglia, a passionate advocate for women’s rights as well as those of prisoners and concerns for the environment, served on the Palermo city council as a member of the Green Party for a dozen years.

We see Battaglia reminiscing with her past lovers and colleagues, all of them considerably younger than her. One was 18 years her junior. At the end of the film, we see Roberto Timperi, an artist 40 years younger, who has introduced Battaglia to yet a new dimension in photographed subjects. In addition to numerous international awards for her work from various disciplines, she became the director of the recently opened Centro Internazionale della Fotografia, Palermo’s first museum dedicated to photography.

Longinotto, in an interview with The Utah Review, says that, indeed, she was “quite difficult” as a documentary subject. “The first time we turned up at her doorstep, she told us to go away. That was something that had never happened to me before,” she explains. “And, then the next morning, it was completely different.” Battaglia was candid and open from that point but she also made it clear that she did not want the film to also be about her children – a point that Longinotto understood as perfectly reasonable. “Indeed, Nelson Mandela had made it a point that he wouldn’t talk about his children,” she adds.

Perhaps the most surprising discovery about Battaglia for Longinotto was the appearance of the much younger Timperi, the companion featured at the end of the documentary who includes trans individuals and cross-dressers in his work. “My feeling was ‘good for you, girl,” she explains. “One has to admire a woman in her middle eighties who can find a companion 40 years younger.” With the exception of a cane, Battaglia’s robustness appears as impenetrable to the energy-draining forces of aging.

Longinotto credits the efforts of Ollie Huddleston, editor, and Clare Stronge, archive producer, for adding the pieces that put Battaglia’s documentary portrait in a much larger context. Despite RAI’s claims that some footage which Stronge requested did not exist, she located it in the vast archives that she was allowed to review. Paolo Uberti translated the hundreds of hours of Mafia court proceedings – most notably, the Maxi Trial that began in 1986 and led to the indictment of more than 500 individuals, many of whom were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Shooting The Mafia is outstanding as a game-changer for understanding more comprehensively the individuals who have dared to stand up against the most ruthless criminals that never hesitate to kill not just their enemies but any witnesses as well. There is a bit of archival footage where neighbors are asked if they saw or heard anything after a nearby Mafia-ordered execution. None of them offer any useful information. A woman mentions that she heard some gunshots but they were probably going after birds.

Indeed, the culture of omerta – that distinctive term for the Mafia’s code of silence – had infiltrated Sicilian society to such an extent that even many innocent figures decided the fear was not worth the struggle for justice. Battaglia justifiably lionizes the memory of Falcone, the magistrate who sought to dismantle the Mafia forever. She remembered him as the sweetest man, the formidable antidote to the toxic masculinity that had poisoned her homeland for many centuries. Battalgia’s story reminds us and compels us to answer the question that has become acutely relevant in our contemporary time: When the time comes for justice, will each of us individually have the courage to do the right thing.

Shooting The Mafia is a production with Impact Partners Film (Dan Cogan, Jenny Raskin, Geralyn White Dreyfous as executive producers) and presented as a Screen Ireland/Lunar Pictures film. It also received a fiscal sponsorship award from the Utah Film Center.

Additional screenings at Sundance will be Jan. 26 at 6:30 p.m. in the Redstone Cinema at Park City, Jan. 27 at 9 p.m. in the Salt Lake City Library Theatre, Jan. 30 at 3 p.m. in the Sundance Mountain Resort Screening Room, Jan. 31 at 2:30 p.m. in the Prospector Square Theatre in Park City, and Feb. 1 at 9 a.m. in Temple Theatre in Park City.