In a scene from Morgan Neville’s documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, which premiered this year at the Sundance Film Festival, Fred Rogers testified at a U.S. Congressional hearing in which support seemed unlikely to approve a budget appropriation for public television. The late U.S. Senator John Pastore, a Democrat from Rhode Island, had rebuffed and swiftly dismissed arguments from earlier witnesses. However, when the host of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood made his case succinctly in the same calm delivery that he used daily on his show, the senator had been persuaded.

The audience at a Salt Lake City screening erupted into loud cheers at the scene. It was just one instance of how the audience was visibly moved by Neville’s documentary. In a later scene, Neville brings in an episode of the show when the late Jeff Erlanger, who became quadriplegic after surgery in his childhood for a spinal tumor, visits Rogers and explains why he used an electric wheelchair. In the episode, Erlanger was 10. Audience members were moved to tears, as they were with a scene from 1999 when Erlanger, 27 at the time, surprised Rogers, who was being inducted into the Television Hall of Fame. Rogers was thrilled, jumping out of his seat and rushing onto the stage to hug Erlanger.

Neville is a gifted documentarian. He won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 2014 for 20 Feet from Stardom, which examined the experiences of backup singers. In 2015, he and Robert Gordon had their documentary Best of Enemies, about the televised debates in 1968 between Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley, Jr., premiere at the Sundance Film Festival.

His latest documentary, a production of Tremolo Productions in association with Impact Partners and Independent Lens/PBS, was acquired before this year’s Sundance by Focus Features and is set to be released in theaters on June 8. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? also was one of the eight film projects which received fiscal sponsorship from the Utah Film Center. Geralyn Dreyfous, the center’s co-founder, also co-founded Impact Partners.

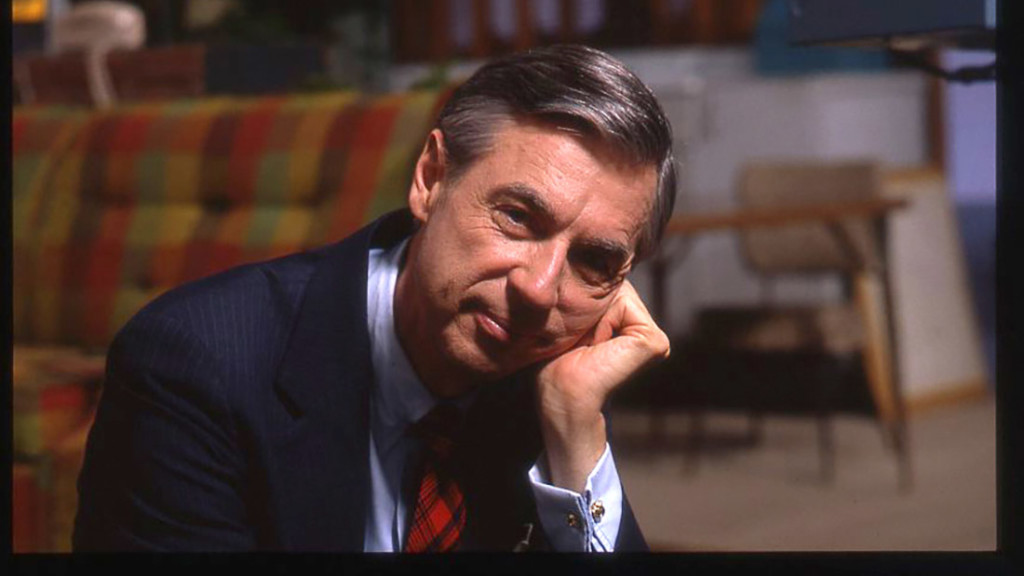

The film strikes a poignant tone and audience members still respond emotionally in positive ways to seeing and hearing Rogers again in various clips taken from interviews and the show. It focuses on how relevant and sustainable Rogers’ legacy is and asks if people would still respond today to Rogers’ messages, as they had done for more than 900 episodes over the course of 40 years.

Neville rounds out the documentary with plenty of interviews from the Rogers family including his widow and two sons as well as those who worked in front and behind the camera. One was Francois Clemmons, an African-American singer who portrayed a police officer for more than a quarter of a century. Even Clemmons is moved to tears, as he recalls his connections to Rogers. Clemmons, who was gay, considered Rogers to be his surrogate father. Neville includes a pair of clips from the show, separated by more than 20 years, in which Clemmons and Rogers soak their bare feet in a wading pool. The earlier instance (from 1969) was significant because many communities still did not allow blacks and whites together in the same pool. But, in both instances, Rogers gently dries Clemmons’ feet with a towel – a humbling scene that is reminiscent of the Christian significance of a ritual that is replicated in Protestant and Catholic churches every year on Holy Thursday.

It would be easy to canonize Rogers but Neville also captures the complexities of Rogers, who like any conscientious creative artist often had to work through doubts about whether he had anything meaningful left to say. He also includes brief clips and images of those who criticized Rogers’ message or were skeptical of his veracity and sincerity as a television performer.

In 1969, Norman Morris, a news writer for CBS Television and the father of two children, wrote an essay for The Atlantic magazine about examples of good television for children and one certainly was Rogers’ show. Morris summarized the work of Rogers along with the efforts of Robert Homme as the Gentle Giant and Robert Keesham as Captain Kangaroo by explaining “they believe that no television personality can serve as a parent substitute. [B]ut they would like to think of themselves as extensions of the parent, offering additional warmth, understanding, knowledge, and guidance.”

This theme is prominent in Neville’s film. As Morris noted years earlier in explaining how Rogers demonstrates to children how to deal with their emotions, “Discuss is a quite proper word because his talks are so personal that they frequently trigger a byplay in which the child may respond vocally to a question and Rogers, anticipating the reply, may follow through to his next point.” In a clip featured in Neville’s film, Rogers explains how this strategy worked in gaining the trust and confidence of children who might wonder if they, indeed, should respond and engage this adult.

Rogers taped his last show in late 2000 and died less than three years later from stomach cancer but his messages and words still are shared extensively, often in the midst of tragedies, such as the Sandy Hook School shootings more than five years ago. The Fred Rogers’ Center has maintained a comprehensive archive of his work and works in parallel with the Fred Rogers Company to continue his legacy not only in children’s television but also for initiatives in a child’s emotional and intellectual development.

Neville’s film amplifies the legacy in a tone that matches precisely to its principal subject. In a difficult time when many wonder if there ever will be another prominent personality like Rogers not only for children but also for adults who remembered what it meant personally to watch his show, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is a welcome testament of reassurance that the words and messages of Rogers always will be within easy reach.