To some, the events of July 12, 1917 that culminated in one of the most bizarre and humiliating responses to labor unrest in U.S. history made the once thriving copper-mining town of Bisbee, Arizona, just seven miles from the Mexican border an “American tragedy”, “an ethnic cleansing” or a “corporate gulag.” Others saw the dramatic moves to end a workers’ dispute as a valiant display of patriotic support for a country that had just entered World War I; the pushback against a labor union many saw as an agent of communism and socialism.

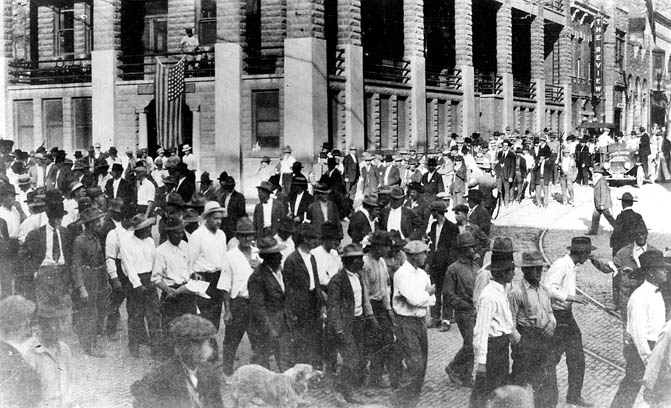

The town’s leaders along with a large phalanx of newly sworn sheriff’s deputies worked swiftly that summer day to deport 1,200 individuals to Columbus, New Mexico, many of whom were immigrants who had asked for better working conditions in the copper mines. Forty years ago, Fred Watson, a man of British ancestry who was one of the people deported, agreed to do an oral history for the University of Arizona. Watson said, “How it could have happened in a civilized country I’ll never know. This is the only country it could have happened in. As far as we’re concerned, we’re still on strike.”

A century later, the story emerges in an unusual commemoration, encompassing a reenactment by townspeople of the strike and the tensions that led to the mass deportation, in Bisbee ’17, a documentary which premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival. Directed by Robert Greene, who also is the filmmaker-in-chief at the Murray Center for Documentary Journalism at the University of Missouri, the film is an Impact Partners presentation of a 4th Row Films production in association with Concordia Studio, Artemis Rising Foundation and Doc Society Circle.

The film is one of the eight Utah Film Center fiscal sponsorship projects to be accepted into Sundance this year, and Geralyn Dreyfous, co-founder of the Utah Film Center and Impact Partners, is executive director.

It is part Passion Play, part “large group therapy session,” as one of the participants in the reenactment says, and, more importantly, a solid contribution to rethink the American West fantasy and the sanitized romanticism that has obscured our collective accurate connection with the history of expansion and development not only in Bisbee but everywhere else in the U.S. West.

Greene wisely leaves open whether everyone agrees on the ignominy of the events a century earlier. There are families, for example, who had relatives on both sides of the dispute. The man who plays the sheriff – a foot taller than the actual law enforcement officer – says during one scene of the reenactment that he definitely feels the action taken was wrong, as the gun-carrying and rifle-pointing deputies escort the deportees on the road. There are families, for example, who had relatives on both sides of the dispute. In 1917, one of the deputized men arrested his brother and placed him in the cattle boxcars used to deport the men. In the reenactment, a pair of brothers who are their respective descendants are caught up in the emotion of the act.

Likewise, Fernando, a young Mexican man, finds unexpected parallels that produce some of the film’s most emotionally intense moments. The gregarious, cheerful young man enjoys his life in Bisbee, initially unaware of what happened a century prior. He has never really been affected by politics – even to be motivated as an activist on issues such as immigration rights. His mother was deported to Mexico for drug charges and imprisoned, while he was just seven years old. As he prepares to act in his character as an immigrant miner, he rehearses a scene with an actor who plays his mother. It is a remarkable instance of personal epiphany for the young man.

It is simultaneously stunning and unsurprising that such a terrible event could have been nearly forgotten. Prior to the deportation, local authorities asked Western Union not to receive or send telegrams for at least 24 hours.

Why did Bisbee happen? In 1917, there were many factors of great tension worrying border towns in Arizona and elsewhere. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) – more commonly known as the Wobblies – had been making inroads throughout the West, as part of a mission to create “One Big Union.” In 1915, Utah executed Joe Hill, the Swedish immigrant and activist who also wrote many of the songs performed in IWW halls and meetings, after he was wrongfully convicted for murder.

Months before the Bisbee Deportation, the U.S. had withdrawn forces in a military operation against Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa, whose paramilitary forces were advancing in the Mexican revolution. And, just three months before the events of July 12, 1917, the U.S. formally entered World War I, which already had inflicted a great deal of damage on German-American cultural heritage. War efforts also meant that the price of copper would rise dramatically, potentially putting Bisbee in a stronger economic position. While most of the historical detail is either summarized or suggested in the film, Greene pinpoints key characters in the reenactment to gauge the spectrum of civic sentiments on both sides that were being played out at the time.

In the Bisbee of 1917, these factors regrettably combined into a perfect storm for such irrational and barbaric action. And, as Greene makes clear in the documentary, there was no legal or financial relief for the gross injustices that had been inflicted upon the individuals. Deportees were warned not to return to Bisbee while others who were not connected to any of the town’s mining business were convicted on trumped up charges if they protested or criticized the companies.

AHS, Pictures-Places-Bisbee-Bisbee Deportation, #43170

A federal commission concluded that no federal law applied to the events, thus allowing the State of Arizona to reaffirm the action as legal according to what it deemed as “Law of Necessity.” Thus, the state did not take any action against the companies but nearly 300 deportees did reach out-of-court settlements with the companies as well as the railroad that was responsible for carrying out the deportation. But, not one case was resolved in favor of deportees who had sued the deputized vigilantes.

While some individuals sympathetic to the decision to deport strikers say in the film it was inconclusive about whether the mining companies were responsible, the federal commission did note the companies, not the IWW, were at fault. Ironically, the IWW, at least for the short term, gained support elsewhere once news spread about what happened in Bisbee. The town would never recover fully. By 1975, copper mining was done. The high school built in the 1950s that could accommodate 900 students now housed just 300.

A fascinating documentary, Greene, who also gave Missouri students in journalism and film studies a chance to work on the project, anchors the historical frame nicely. Bisbee ’17 reminds viewers that these issues always are nearby, especially when the ghosts remind us of the costs and consequences of making bad policy and immoral decisions when it comes to immigration, economic justice, environmental integrity, and corporate responsibility and social conscience.

Remaining screenings of Bisbee ’17 are as follows:

Thursday, Jan. 25, 5:30p.m. — Prospector, Park City

Friday, Jan. 26, 8:30 a.m. – MARC, Park City

For Sundance program and ticket information, see here.