After a 2019 survey by the American Bar Association revealed some discouraging gaps in civic literacy, Bob Carlson, then ABA president, said, “We cannot be content to sit on the sidelines as democracy plays out in front of us. For the sake of our country, we all need to get in the game.”

For example, 20% of the respondents believed that the first 10 amendments of the U.S. Constitution are called the Declaration of Independence instead of the Bill of Rights. Meanwhile, some respondents were confused about First Amendment protections: “Nearly 1 in 5 said freedom of the press is not protected by the First Amendment and 20 percent said the right of people to peaceably assemble does not fall under the First Amendment. More than half incorrectly think the First Amendment does not permit the burning the American flag in political protest under the First Amendment.” Also, nearly 1 in 10 believe the first three words of the U.S. Constitution are “I Pledge Allegiance.”

Some 15% believed erroneously that the “rule of law” means that the “the law is always right.” Approximately 1 in 6 believe that due process is available only to U.S. citizens while 30% believe that non-citizens do not have the right of freedom of speech.

Meanwhile, a wonderful example of civic literacy platforms for public engagement comes through in Heidi Schreck’s 2017 play What the Constitution Means to Me, which is receiving a spirited, well-acted production by Pioneer Theatre Company.

The play has had solid legs. Nominated for two Tony Awards, the show had an extended sold out run on Broadway. The same level of response has followed the show elsewhere and a filmed version, starring the playwright, was released on Amazon Prime Video last fall.

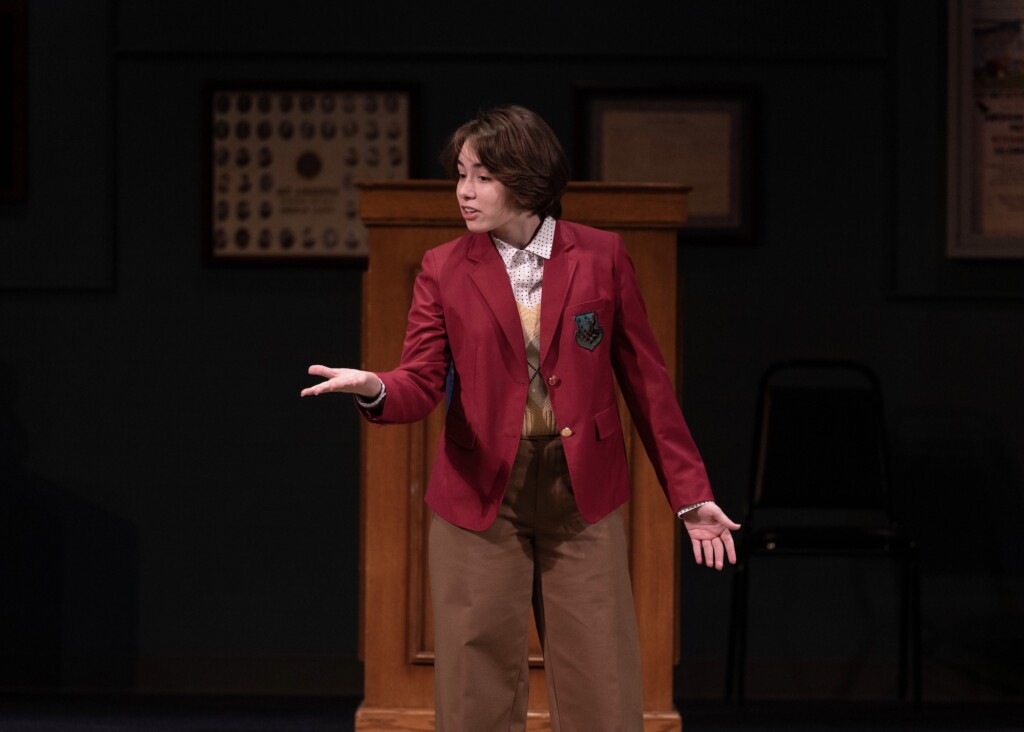

Directed by Karen Azenberg, the Pioneer Theatre production pops with excellent performances by Laura Jordan as Heidi, Ben Cherry as the Legionnaire and as Mike, and, for opening night, Taryn Bedore as a debater. The script provides a template, along with various options for customizing productions to local audiences. For this run, the role of the teen debater (much like Heidi was when she was a teen) is being rotated among several young actors (Bedore, Sofia Brinkerhoff, Naomi Cova and Abigail Knighton). The coda section of the play with the debate between the actor portraying Heidi and the young debater puts the appropriate animated punch and zing to the play, which ensures it does not become pedantic.

What clearly has made this autobiographical play especially popular is how Schreck instructs the actors to ad lib as appropriate and to engage the audience as necessary. As the play opens, Heidi announces she will now return to her 15-year-old self, when she competed in the American Legion Oratory Contest in Wenatchee, Washington.

Heidi, who explains that she has always been fascinated by the Salem witch trials, speaks extemporaneously on the “crucible of the Constitution.” While a crucible is a “witch’s cauldron,” she adds that a crucible is also a “severe test of patience and belief.” She goes further: “The Constitution can be thought of as a boiling pot in which we are thrown together in sizzling and steamy conflict to find out what it is we truly believe.”

It is about as a good metaphor that is available to describe the current state of politics and public opinion and perceptions of law and the contemporary relevance of the Constitution. Indeed, references to two U.S. Supreme Court cases in the play, along with brief snippets of the recordings from the arguments presented when the justices heard these cases, sharpen some of the most timely (even urgent) overarching concerns about constitutional protections. One is the 1965 case Griswold v. Connecticut, in which the justices ruled that the state’s ban on the use of contraceptives violated a right to marital privacy. The second is Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzalez, a 2005 decision in which the justices ruled that Gonzalez had no constitutionally-protected property interest in the enforcement of a restraining order, and therefore could not claim that the police had violated her right to due process. She had obtained a restraining order against her estranged husband but when she asked the local police to intervene when he abducted the three children in the family, law enforcement officials delayed searching for them in order to wait and see if he would return the children. But, later that evening, he had murdered the children and then was killed by police when he opened fire in police headquarters.

Schreck’s script encompasses many types of abuse, racism and violence that historically were considered taboo for frank public dialogue and debate when it came to the constitutional realm: LGBTQ rights, the rights of immigrants, access to abortion and contraceptives and protections for victims of domestic violence and severe abuse. The play’s deepest dive in constitutional territory revolves around the Fourteenth Amendment because of its breadth and depth of perspective about due rights and procedural process.

The play effectively strikes an emotional tone without appearing to be divisive or impulsive. The emphasis on the orderly elegance of classic extemporaneous oratory and procedural rules of proper debating frame one of the broader takeaways from the play. That is, our Constitution is an arguably imperfect document, but nevertheless its resilience as a living one open to amendments, as needed, remains just as vital as ever. Bedore’s impassioned delivery of that point, echoing the same idealistic fervor that the young Schreck expressed when she was 15, smoothly brings this full circle by the end of the play.

The run continues through April 22. For tickets and more information, see the Pioneer Theatre Company website.