In The Poetics of Space, the 1957 book by French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, the interactive effects of our minds with our most intimate, familiar surroundings were the focus of his phenomenological approach. Bachelard saw the childhood home, for example, as a theatrical space that inspired expressions of our dreamlike imaginations. With Bachelard, it was French music and poetry. He wrote that “poetry gives us not so much a nostalgia for, youth, which would be vulgar, as a nostalgia for the expressions of youth. It offers us images as we should have imagined them during the ‘original impulse’ of youth.”

He added that such artistic engagement was good for engaging the nonrational parts of our existence. “To the function of reality, wise in experience of the past…should be added a function of unreality, which is equally positive,” Bachelard explained.

In Static Patterns: The Art of Robin Banks, a show at the God Hates Robot Gallery in downtown Salt Lake City, Banks explores the poetic space of they’s childhood life in a delightfully perceptive array of works in mixed media that include pen-and-ink drawings as well as paper mache sculptures and wall pieces.

Banks compels viewers to contemplate the question: “When the home you’ve built yourself is bits and pieces of childhood nostalgia, how do you find the room to grow and to age? Without the ability to adapt and reconstruct, stagnation is inevitable. The pattern is static. An artist imagines and creates. But can they reevaluate?”

Banks, who came from Crosby, North Dakota and lived in West Jordan, Utah, imbues the works with solid interpretations of Bachelard’s philosophical sensibilities about how we meaningfully can appropriate memory and nostalgia for our own well-being. In an interview with The Utah Review, Banks says, “During my childhood, we moved around a lot – often once or twice a year, if not more. My father was absent and I did not feel safe after school. So, the idea of sequestering yourself in your childhood home made sense and I realized that it would be the place I would have for the rest of my life.”

Banks is a self-taught artist but Shari Acevedo, Banks’ mother, also is a sculptor who also works in oils, aqua-media and pastel. A descendant of Mormon pioneers who came from Norway, she has participated in many art shows and has earned awards and honors at exhibitions across the country.

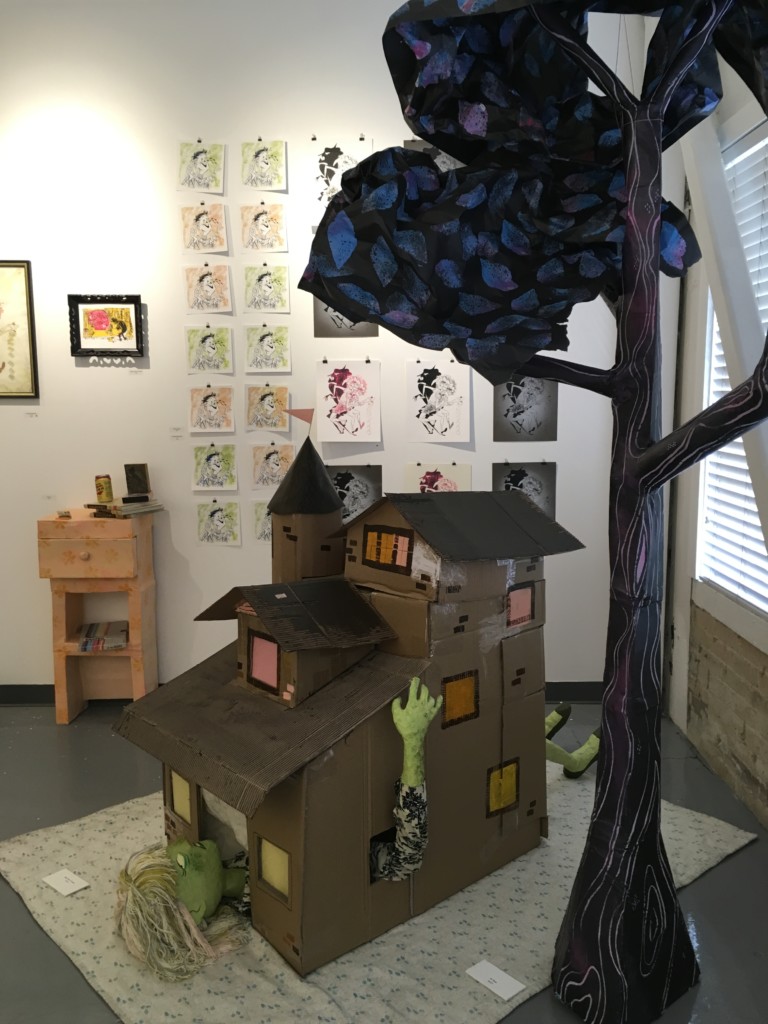

The show also signifies an expansive phase in Banks’ work that has emerged over the last several years. The use of paper mache, for example, is not merely a throwback to a medium that almost every child worked with in an elementary school art classroom. Banks is well known as a skilled illustrator in pen and ink and they’s interpretation of pop culture icons, especially from cartoons and other aesthetic elements from past generations.

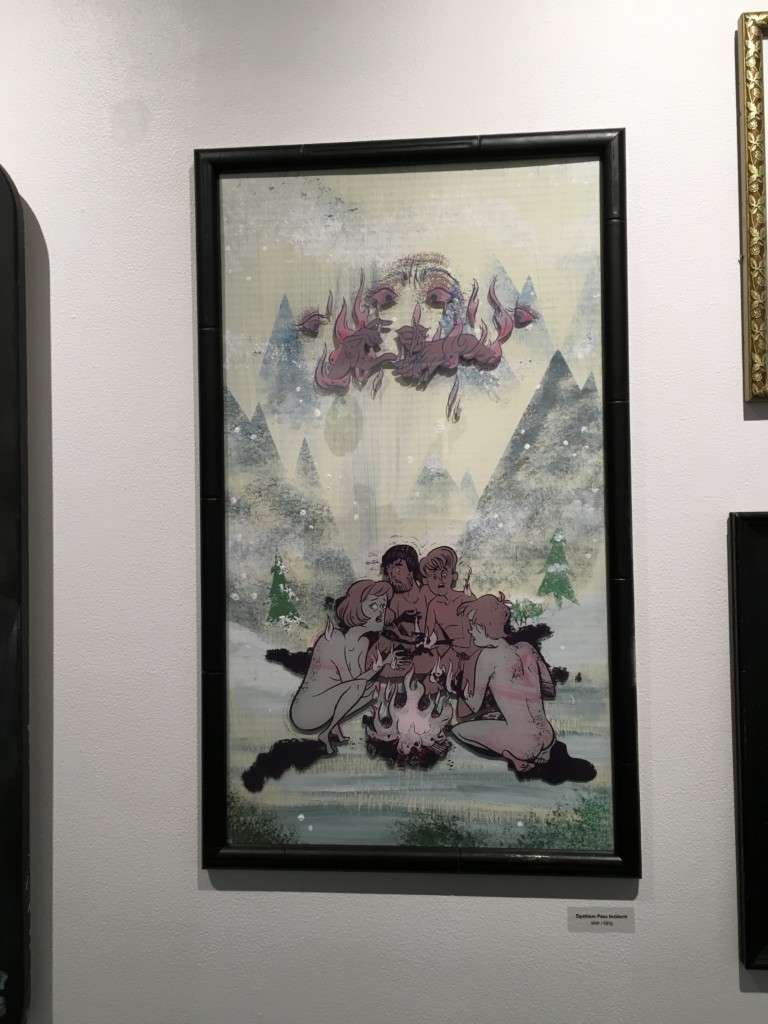

The latest show echoes a style and spirit, especially from the Sixties and Seventies. Banks is a cartoon connoisseur of the classics, stretching back to Tom and Jerry and Betty Boop. A paper mache wall hanging offers up a seemingly disparate array of images, hues, textures and styles that magically coalesce as an enchanting bit of reverie. Banks’ instinct for collages justifies the Static Pattern title of the exhibition – the childish elements do not predominate but they certainly are forever embedded and key to understanding the adult’s vision of what that ‘original impulse’ of youth meant.

Another piece recalls the comfort of home with a table and vegetables. The largest piece is a house with a tree and a person stuck inside but looking out – a spot-on comprehension of Bachelard’s sentiments.

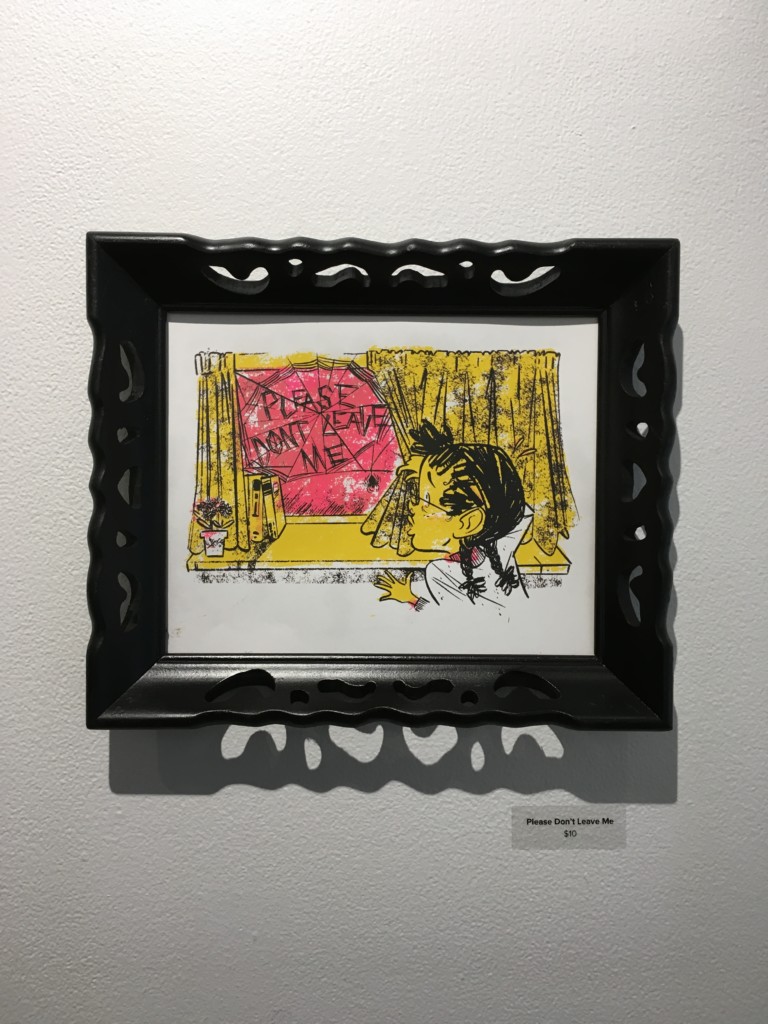

The exhibition also showcases Banks’ finesse with capturing what The Utah Review previously noted as “the consistently effervescent appeal of pop culture.” The show’s illustrations, as previously explained, weave “camp and kitsch with pop, comic and vernacular tones along with wisely selected inflections of retro, mod and classic and even juxtaposed instances of creepiness and cuteness.”

Banks is especially adept at appropriating a comic book or cartoon character (for example, one that might have appeared in the classic Archie comic book series) without imitating it or making the piece derivative. Banks’ work always draws the eye to an underlying incisive statement that subverts traditional perceptions about gender, identity and fitting into a community where a predominant socioreligious culture, for example, often resists valuing or affirming ‘The Other’ as an equally respected member of the neighborhood. But, Banks also never lets the seriousness completely overwhelm the whimsical potential. Many of the drawings embed a ironical bit of humor, gag or pun in a simple story scene.

More about Banks’ work can be found here and here.