For Gamut, its spring show, Repertory Dance Theatre (RDT) will present Solfège, a new commission from choreographer Yusha-Marie Sorzano, who is making her first appearance with the company, along with two outstanding audience-pleasers from the repertoire: Ihsan Rustem’s Hallelujah Junction and Lar Lubovitch’s Marimba. Performances are scheduled daily at 7:30 p.m. April 11-13, in the Jeanné Wagner Theatre at the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts.

In an interview with The Utah Review, Sorzano (note: her first name is pronounced “Ooo-sha”), who took dance lessons in ballet and jazz at a magnet school during her childhood, said that she has found her assertiveness as a creator, by not thinking about one genre or by limiting herself to a specific movement language or vocabulary. “It is about weaving all types of vocabulary together to create emotional arcs that reflect the true heart and soul of an artist,” she added.

This is what makes Solfège an ideal new work for RDT’s Gamut theme. Originally from the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, Sorzano said that in the case of Solfège, she knew from the point of conceiving the piece what music she wanted to use, which is different than what she has typically experienced in the creative process.

The musical source is Symphonic Poem of 3 Notes, a 2011 work that the Teatro Real Opera in Madrid commissioned from Chinese composer Tan Dun to commemorate tenor Placido Domingo’s 70th birthday. Tan, in a program note, explained that when one raps the tenor’s first name, three solfège pitches (LA – SI – DO) build and anchor the work’s integrative theme, which signifies, to quote the composer, “the start of a new life, like a dream it unfolds with the sounds of birds, wind and rain.”

The music includes symphonic rapping, hip-hop phrases, sounds made with stones, industrial brake drums and car wheels, along with chanting and stomping before the solfège notes return to their natural origins for a new cycle to begin.

Deeming it a brilliant composition, Sorzano explained that her instincts guided her to envision how dance could replicate the complex world Tan envisioned in this music. Coming into the studio to work for the first time with the RDT dancers, Sorzano decided not to have any specific movement phases and fragments prepared ahead of time because she wanted to involve the dancers as much as possible in building a world that would celebrate the music that accompanies it.

Once everyone figured out how to count the ever shifting meters in the music, Sorzano said it quickly took shape in setting movement to represent what these sounds resembled. For example, she looked to other visual references as a guide, including Guillermo del Toro’s spectacular film Pan’s Labyrinth (2006). Tan’s score lends itself to all sorts of fantastical imagery. There also are temple bells to herald the start of the day, the sounds of strings emulating birds taking off into the morning sky, and the shouts of the three solfège notes which have a purifying effect on a body, which rids itself of stress, aches and pains.

With Solfège, “you cannot go wrong with this music, because it really is perfectly made for dancers and they get it,” Sorzano said. As for her first time working with RDT dancers, she added, “Each day, I was very happy going to work and having that same feeling coming home. All of them are kind human beings who made me feel deeply safe.” Sorzano added this is significant to her personally, “because I make my best works when I am vulnerable and the RDT dancers were willing to go for and try anything that we talked about in the studio. Their enthusiasm and eagerness were evident from day one.”

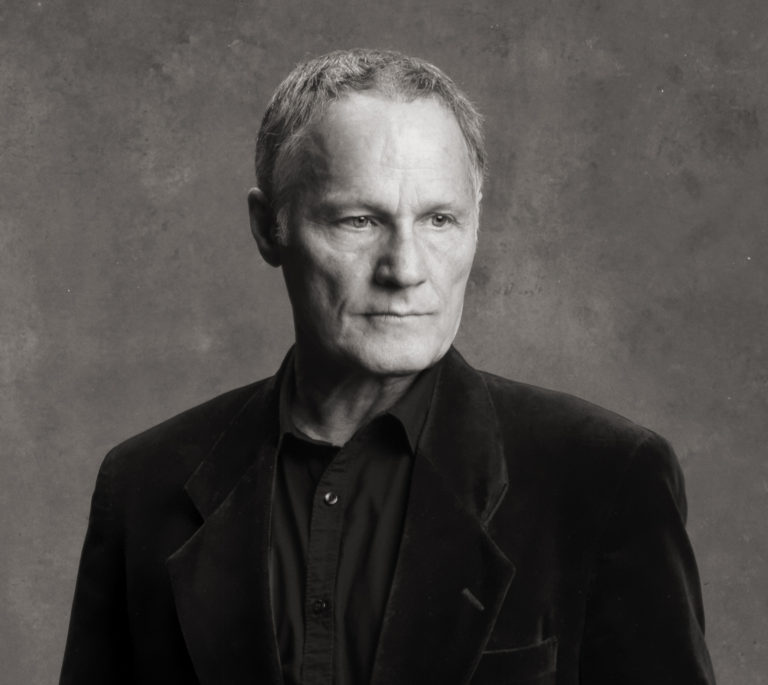

Sorzano is a member of Camille A. Brown & Dancers and is founding co-artistic director of the newly formed Zeitgeist Dance Theatre, as well as serving as associate director for program development with Francisco Gella Dance Works. She also teaches ballet as special faculty at the California Institute for the Arts and is at work as choreographer for Jeannette, a new musical.

She has choreographed works for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Ballet Idaho and Santa Barbara Dance Theater, among others. Sorzano has been a research fellow at the New York Public Library’s Jerome Robbins Dance Division, an artist in residence at the Watermill Center in New York, a recipient of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s New Directions Choreography Lab and a National Young Arts Foundation Dance Artist-In-Residence.

One of RDT’s most popular recent commissions, Hallelujah Junction by Ihsan Rustem (2021) fits beautifully into Gamut. The music comes from a 1996 score by John Adams. While music by Stravinsky and Copland has always inspired many choreographers, Adams also has been a popular choice, even though his music was not written specifically with dance in mind. Choreographer Peter Martins, who used Adams’ Hallelujah Junction for his 2003 piece Guide to Strange Places recalled in a Playbill interview with Frank Oteri, what the composer told him, “‘All you should know is that Hallelujah Junction is a little town in Northern California that has a gas station and a grocery store.’ I said, ‘Is there anything else I should know?’ and he said no.”

Thus, one easily comprehends how Rustem visualized the score as an ideal canvas to set a work where sections can be pulled out with wonderful results featuring not just the company’s dance artists as a whole but also solos, duets and other groupings. Likewise, minimalistic musical scores such as these make smooth shifts in tone and character of the movement as it progresses.

The RDT commission was a “long time coming,” Rustem said, in a 2021 interview with The Utah Review. Nicholas Cendese, RDT artistic associate and development director, met Rustem at a concert at Brigham Young University and the connections were made. “I remember watching rehearsals of RDT four years ago and I was impressed by the great spirit I saw and learned of what a landmark and pillar the company was with its rich history,” Rustem recalled.

Thus, the commission came at the right time for Rustem, who set the work after the pandemic’s “long pause,” as he described it. “It felt right to use the music of Hallelujah Junction on this company at this time and at this place.”

In 2021, Rustem said the piece is joyful and celebratory, as a signal that it is okay to do so in relief from recent mishaps and misfortunes. And, of the more than 40 pieces he has set as a choreographer, Rustem explained that he has never had a more fun time working with dancers than with this latest commission. “I cannot recall laughing so much and the dancers clearly had a good time as well,” he added. “But, they also worked their butts off and it was impressive to see how they work as a team.”

Rustem came from a musical background. He started violin lessons at the age of six and, as he recalled, “it seemed to come quite naturally.” He played in his youth orchestra during his high school years but by the time he was 15, he realized that he disliked it. But, his musical ear also stayed with him so hearing Adams’ Hallelujah Junction ignited the choreographic interpretation. Indeed, a trained ear picks up on the waves of nuanced shifts taking place in the music. “I realized I could dissect the music and see it on stage so that the dancers could sing the movement from their bodies,” he explained.

Rustem said he set a quick pace in the piece, beginning with a series of “spicy, fast solos,” introducing each member of the RDT company. Staying true to Adams’ earlier comment about the music’s plainspoken significance, he developed the work with duets emphasizing bits of gestures, which do not have a particular reason or meaning. The fast sections of the opening culminate in a dynamic crescendo before settling into a tender heart-tugging duet. While Rustem said the movement of the duet is set without specific gender roles in mind, his is followed by another fast section, which Rustem added is “incredibly one of the fastest things he has ever done,” while weaving in the joyful lyricism embedded in the music.

Adding a touch of history and masterful craftsmanship, the Gamut program includes the re-staging of Lar Lubovitch’s classic “Marimba” (1978). Featuring music by Steve Reich, Marimba showcases nature’s enduring and relentless beauty, featuring 10 dancers including two guest artists. Katarzyna Skarpetowska returned as Lubovitch’s repetiteur to re-stage the work.

Lubovitch is one of the foremost American choreographers whose career has lasted more than 60 years. Starting as a gymnast, Lubovitch, in a previous interview with The Utah Review, said that the spark to switch to dance came after watching a performance of the José Limón Dance Company. “It was instantaneous,” he recalled, “like the proverbial light bulb.” He set out ambitiously, first at the University of Iowa and then later at The Juilliard School. He whet his appetite for choreographing by attending annual American Dance Festival along with workshops and sessions with contemporary dance legends including Limón, Martha Graham and Alvin Ailey.

But, as much as he absorbed the knowledge of the titans of the art form, he quickly realized that it was “absolutely imperative” to develop his own movement language and vocabulary. For example, a 2012 review in The New Yorker reminded readers of how “accomplished he is at ravishing the eye.” The review opened with, “In Lar Lubovitch’s choreography, the swirl of dancers moving in unison to a sweeping piece of music is a thrilling sight. Underneath his lush phrases, individuals are always visible, their personalities emerging in the clarity of their dancing.”

Lubovitch’s connections to RDT go back to the 1970s, in the company’s first decade, when Linda Smith, one of RDT’s co-founders, was also a dancer. RDT was the first company to commission a work from Lubovitch – Sessions, which premiered in 1975.

Lubovitch said that from his earliest choreographic experiences he has been devoted to selecting music that opens up to sculpting movement that enhances the experience of listening to and letting the music wash over the experience for both dancers and audiences. He was one of the first choreographers to use the music of minimalist composers in the 1970s as foundations for setting dance movement, notably Steve Reich and Philip Glass. Minimalism might have been at the front and center of the music stage for barely the span of the 1970s but its impact has stretched into the current century.

Lubovitch accurately described the period of minimalism as a “gentle rebellion.” Indeed, minimalism offered the effective rationale for doing away with the distinctions between classical or high art music and popular or low art counterparts. It was a democratizing moment for music, helped along by dance artistry’s wel furnished instincts for artistic democracy, an ideal that Lubovitch has welcomed and championed in his career.

Certainly, Reich and his minimalist colleagues embraced the musical foundations of Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent and other Eastern traditions. These include the music and dance of Bali as well as aesthetic influences from Sufism and the Buddhist ideal of satori. There also was the character of shamanist rituals and polyrhythmic musical structures, which enhanced the effects of looping repetitions of rhythm. The effect could at times become a gentle luring into a pleasurable state of semi-hypnosis. Hence, Reich’s music propels Lubovitch’s Marimba, which he said was “choreographed almost immediately.” To wit: Lubovitch added that it is to embody and emulate a trancelike state. Listening to Reich’s music, one can make the connection to the foundations of the disco and electronica aesthetic that emerged and carried over long past the brief moment minimalism enjoyed in the composing spotlight.

For more information, including ticket details and showtimes, please visit rdtutah.org.