A modern dance artist’s solo is more than an opportunity to demonstrate technique. It offers a rare moment for the individual artist to command the stage: to present their inner persona in ways that transcend the kinetics of the company ensemble performance.

Repertory Dance Theatre’s (RDT) latest concert film Flying Solo stands out as the best filmed version to date of a Salt Lake City performing arts group’s presentation during a prolonged period of COVID-19 restrictions of live performances. Presenting a program of works spanning 85 years and including two world premieres, the company’s eight dance artists rise above limitations while revealing their inner artistic passions and aspirations.

Many of the performances are moving and eloquent. This is a major feat because virtually all of the coaching from choreographers took place via remote conferencing. The inherent advantage of performing virtually every work on the program as a solo is that the dance artist could do so without a mask. Filmed and edited by the locally based Wonderstone Films, Flying Solo, which also continues celebrating the company’s 55th season (its emerald anniversary), is destined to be an insightful archival piece for documenting this phase of RDT’s history.

One premiere was Remote by Marina Harris, featuring short solos for each of the eight RDT artists that were matched with music by composer Scott Killian. In a phone interview from her Nova Scotia home with The Utah Review, Harris, who was with RDT for many years, explains how she evolved in her creative process for Remote from setting movement for a single solo to one for each dance artist.

Working with nearly 50 pieces of music that Killian provided, Harris selected seven, based in part on the preferences listed by each RDT artist. From the onset, Harris tried to visualize how the movement would appear to someone watching the performance on a small screen, such as a tablet or smartphone. When she learned that a crew would be shooting the performances from three different angles, Harris tweaked her own expectations for how the dancers would move in the space.

Harris worked via Zoom conferences with the dancers. “It was an odd experience,” she says, such as when the internet connection stream periodically buffered and froze images of dancers seemingly suspended in air or the screen went blank when a solo was being performed. A viewer could see each solo as how characters in an interactive video game might introduce themselves as they demonstrate their ‘signature’ movements. There are some basic threads linking one dancer to another, with some repeated movement phrases.

“In most instances, we worked really fast and things kept shifting because no one was sure whether the performance could go on as live or if it would end up being filmed,” she says. “I didn’t realize how exhausting working this way was, especially when you’re reaching across the continent by Zoom, watching dancers on a screen where they appear just a few inches tall. The dancers were great and put in enormous effort, and sometimes watching it on an iPad screen, you can’t really see the effort that goes into feeling the energy to jump higher or go lower.” Remote is truly a work conceived for the portable screen but it also showcases nicely the distinctive personalities of the company’s artists.

The other world premiere, The Impermanence of Darkness, was choreographed by Nicholas Cendese,, RDT artistic associate, for Jaclyn Brown, and is dedicated to Barbara Lewis, 86. Cendese and Lewis teach together in a Music and Motion class for the senior living community at Sagewood in Daybreak. Again, the themes of rising above limitations and finding peace on one’s own terms are evident as Brown traverses the stage, contemplating her options. Cendese’s musical selection for the work is on point, featuring the Cum dederit movement from Vivaldi’s Nisi Dominus. The music builds organically with ascending harmonic lines, signifying the eventual reach to a clear emotional epiphany.

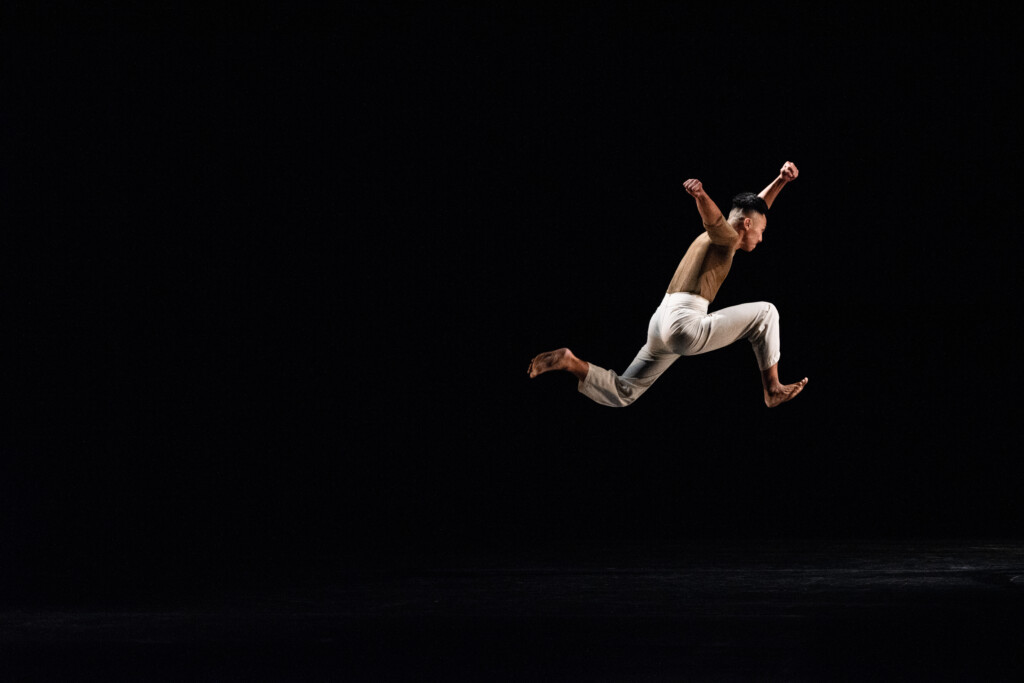

Solos from modern dance’s earlier periods stood out magnificently. From 1935, excerpts from Ted Shawn’s Kinetic Molpai — Solvent/Folding and Unfolding, with music by Jess Meeker — were given their full artistic justice by Dan Higgins. This is a classic example of the raw, virile, muscular, athletic movement language that distinguished a good portion of Shawn’s creative oeuvre. The visual effect of Higgins’ performance conveyed convincingly the essence of the historical period in which this work was created.

A 1948 work first set for RDT in 1998, Spanish Dance: An Impression of Flamenco Dance by Daniel Nagrin, epitomizes modern dance’s capacity to translate the signature elements and gestures of classic flamenco style into a curious, ironic contemporary expression. Elle Johansen effortlessly captures the translation intended in Nagrin’s work, with music by Genevieve Pitot. RDT’s Lynne Larson restaged the work, along with coaching by Nina Watt.

Lauren Curley performed a solo excerpt from Zvi Gotheiner’s Chairs, a work created in 1991 and restaged for this latest performance by Angela Banchero-Kelleher. The solo, set to Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in F Sharp Minor, Op. 23, No. 1, is staged with the dancer seated in a chair, bathed with light from above the stage. Curley’s flawless performance revolves entirely around the chair, as she swivels continuously, her arms swinging out and in with complicated patterns and her movements aided by the natural momentum in her upper torso.

Meanwhile, RDT’s newest member, Kareem Lewis, channeled precisely the mythical majesty of José Limón‘s ground-breaking choreographic voice in Pegasus, a solo from The Winged with incidental music by Hank Johnson, which received its premiere in 1966. Costumed in gold, Lewis evokes the modern representation of Pegasus as the horse of the nine Muses. Watt also directed and staged the solo.

Three previous RDT commissions also were reprised. From 1987, an excerpt from Peepstone, a work by Douglas Dunn, was restaged by Lynne Larson to accommodate pandemic measures. It’s essentially a movement puzzle, as four dancers simultaneously work through their own respective ordering of 16 different movement gestures and phrases, accompanied by Mozart’s Eine Kleine Gigue in G, K. 574. Like the music, the quartet of dancers darts in and out of the angular rhythms which cross each other continuously and their movements echo the seemingly disoriented chromaticism of the piano part. First, the four male RDT dancers, wearing masks, perform their pieces of the puzzle (Trung ‘Daniel’ Do, Dan Higgins, Jonathan Kim and Kareem Lewis). Then, the four female RDT dancers (Jaclyn Brown, Lauren Curley, Elle Johansen and Ursula Perry) follow suit. At the end of the film, the two sets are spliced together and Dunn’s puzzle makes perfect sense which belies its surface randomness.

One of the pieces commissioned for RDT’s Sounds Familiar concert last year was Sounding I, II and III, a triptych of solos set to the famous Prelude from Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007. Keeping with the theme of Flying Solo, this was a perfect work for reprising. Each solo was presented separately at various points in the program. Featuring the same three soloists as in the premiere (Do, Brown and Kim), the filmed version sharpens just how well Heller and the dance artists rose to the initial tasks of the originating commission. Do and Brown convey the dilemma of overcoming the daunting complexities of tackling any of Bach’s unaccompanied music pieces. As mentioned previously at The Utah Review in context with this work, purists demand unwavering allegiance to technical accuracy of interpretation while others believe that one should not deplete such great music from its emotional core. Do and Brown interpret effectively the emotions of struggle, frustration and liberation. In the third solo, Kim synthesizes the experiences of the two predecessors, finding that gratifying balance of “yes, there it is,” and discovering the emotional impact of not only executing the technical demands of the work but also of communicating genuine artistry that illuminates the creative expression’s spiritual potential.

The other commission from Sounds Familiar featured in Flying Solo is A Thin Line, Sharee Lane’s touching, poetic rendering of the aria O Mio Babbino Caro from Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi. Captured on film, Perry’s solo rose to the benchmark of its live premiere in 2019. She elucidated the innocent appeal associated with the main character’s daughter, ending on a radiant note, precisely matching every line in one of opera’s most familiarly gorgeous arias.

Linda C. Smith, RDT’s executive artistic director, in an interview with The Utah Review, says that the solo concert was ideal for numerous reasons. “A solo program allows the dancers to show off their unique characteristics and this way audiences could see their faces without masks. And, the chance to perform a solo is really a special gift to a dancer. We enjoyed resurrecting some of the works from our historic repertory,” she says. Smith adds that all of the male dancers, for example, learned the Shawn solo that Higgins performed. Lewis’ solo was a fortuitous choice, given that he already had learned the Pegasus solo as a student of Watts.

In part of the narration by Ricklen Nobis, the film includes a tribute to Kay Clark, a member of RDT’s national advisory board, who died last May. Clark was one of the founding artists of RDT in 1966 and she served as co-artistic director for seven years until 1983. As the film tribute mentions, “Kay was RDT’s artistic princess … a beautiful and gifted artist and a friend who left a legacy that continues to inspire the RDT organization as well as the people who were fortunate to know her… and to love her… and to see her dance.”

The film is available for purchase to stream on demand through Dec. 31. For more information, visit the RDT website.