To many outside of the working world of science, the most important work of discovery might seem mundane and inconsequential – especially when it was conducted by women. Margot Lee Shetterly’s 2016 nonfiction book Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race (Harper Collins) was adapted to film which has been an eyeopener at the box office (nearly $250 million in box office gross revenues) and among the general public.

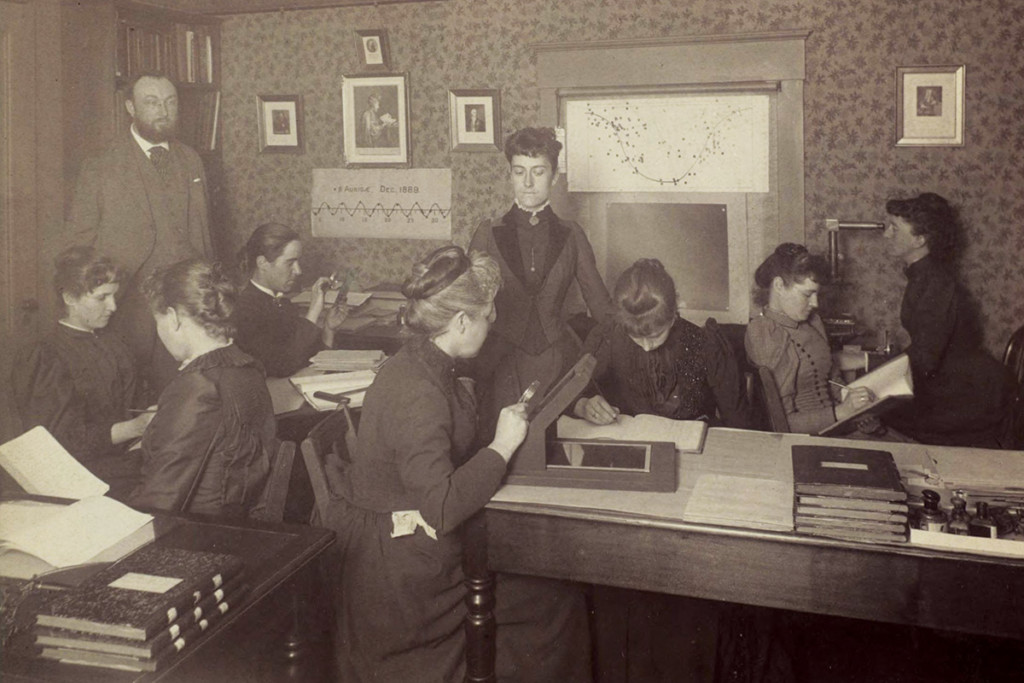

Released this year, Dava Sobel’s book The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars (4th Estate) examines the ground-breaking work of Henrietta Leavitt and her colleagues in the Harvard College Observatory, starting in the 1890s. As Sobel explains in an interview with the Harvard Gazette, he first heard of Leavitt when he asked astronomer Wendy Freeman about her work on the expansion of the universe as part of the Hubble Space Telescope Project. He dug further, adding that “I found out that Leavitt had been working with literally a room full of women at Harvard, which was a big surprise because Harvard in the 1890s was not really a place one thinks of as being especially welcoming to women. But the observatory was a separate institution with its own director and its own financial responsibility. It already had a history of women working there. That struck me as powerfully interesting, as well as the notion that the work these women were doing was really important.”

In both instances, the women were “human computers,” carrying out the massive series of calculations by hand. In 19th Century and early 20th century Harvard, it was first women who were relatives of male observatory employees and were recruited to handle the computations based on their studies of photographic plates. Later, students from nearby women’s colleges were brought aboard. Sobel recounts the work of Williamina Fleming, who was a maid working for the wife of Edward Pickering, the director of the observatory. She discovered 10 stars, more than 300 stars with variable brightness, and classified more than 10,000 stars using a set of computational standards she developed. In 1899, she was named Harvard’s curator of astronomical photographs.

Leavitt achieved even more consequential results. Having discovered more than 2,400 variable and pulsing stars in a 14-year period, she found a pattern in the brightness of a group of stars known as the Cepheid variables. The discovery was a momentous advancement in astronomy in the early 20th century. It gave the foundation for Edwin Hubble’s work proving that the Milky Way was not the sole galaxy in the universe and that the universe was expanding.

However, Leavitt received little or no credit for her work, as Pickering decided to publish her work under his own name, only citing Leavitt as having prepared the information, according to the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). She died in 1921, a fact unknown to several members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences who proposed that Leavitt should have been nominated for the 1926 Nobel Prize.

Leavitt’s extraordinary story is imagined and interpreted in the 2015 play Silent Sky by Lauren Gunderson, which will be staged by the Pygmalion Theatre Company in a run beginning April 28 at the Black Box Theatre of the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts.

And, in a performing arts genre where finding productions of work by women playwrights can be difficult, Gunderson has the honor of being the second most produced living playwright in the U.S. for the 2016-2017 season, according to statistics compiled by American Theatre. Pygmalion’s production of Silent Sky is the 16th of a Gunderson work currently in the country. Most of the productions involve two of her works, I and You, a coming-of-age play about high school students, and Silent Sky , which humanizes the dispassionate pursuit of science with the personal motivation, compassion and hope that drives Leavitt and her colleagues to make their imprint not just in the observatory but also in their daily lives and relationships.

Mark Fossen, director of the Pygmalion production, calls the play “beautiful and elegant,” and he adds the play asks the right philosophical questions. “Henrietta is exploring her place not just in the observatory with telescopes but her overall place in the world and even the universe. There was this profound realization that the universe is expanding and that the Milky Way was not just the only galaxy. And rather than see such a collection of geniuses as isolating, Henrietta finds a family, a community to build relationships.”

Fossen recalls a recent rehearsal in which a grandmother, who has been a paleontologist for more than 40 years, brought her granddaughter to see some of the play. The point of the challenges women have faced in science is clear, regardless of century or decade. Vera Rubin, the great astronomer who died late last year, recalled the difficulty in raising girls to have the confidence to work in science, where encouraging role models are a rare find. Likewise, the AAVSO noted, in the case of Leavitt, that “even highly educated and brilliantly talented women who in a fairer world would have been respected as equals by their male peers, were all too often resigned to taking a lesser role, and were often just quietly grateful to be given any sort of role at all.”

Hannah Minshew, who plays Leavitt and was initially planning to become a geologist before pursuing a career in theater, says the role has inspired her in different ways. “I have learned a lot about astronomy that I didn’t think I would be able to understand,” she says. “She is a woman who plans to be exceptional and extraordinary and I always have felt that way in my life.”

The cast includes Brenda Hattingh, Elizabeth Golden, Michael Scott Johnson and Teresa Sanderson.

Silent Sky is not the only Gunderson play to highlight science. Others include Ada and the Engine, with Ada Lovelace, a Victorian mathematician who is acknowledged as writing the first computer algorithm. In Émilie: La Marquise du Châtelet Defends Her Life Tonight, Gunderson celebrates the 18th century physicist whose annotated, translated version of Newton’s Principia is still referenced actively.

Performances will run through May 13 on Thursday, Friday and Saturday at 7:30 p.m., Sundays at 2 p.m. Ticket information is available here.

Thanks, as always, Les. Another brilliant, engaging review. Thank you.