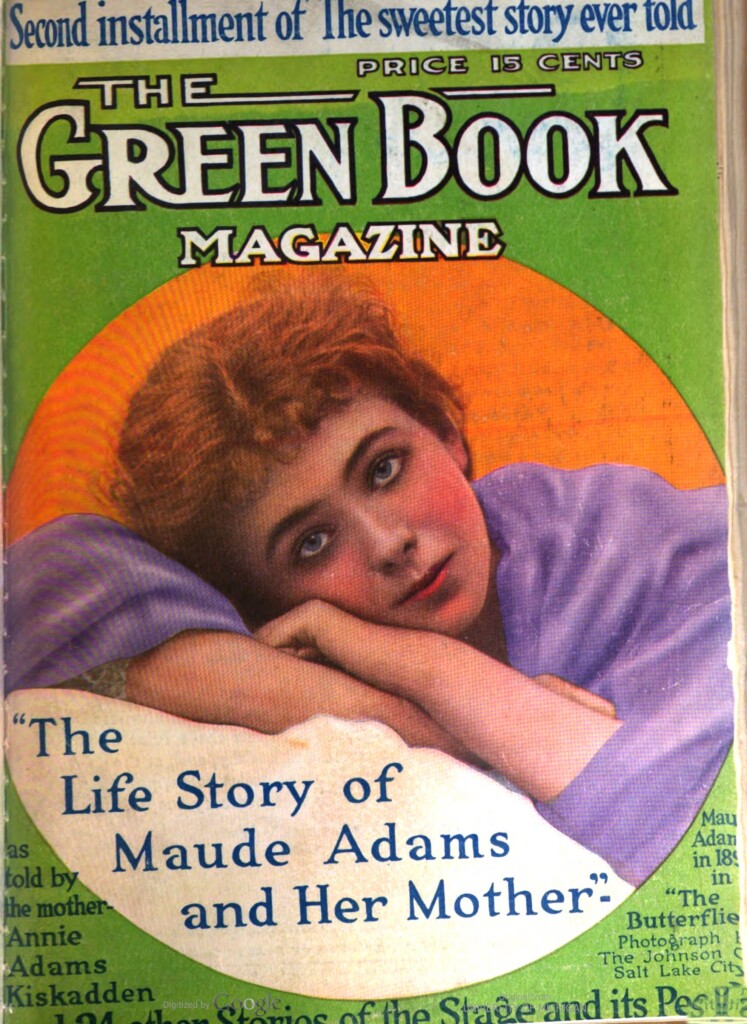

In the summer of 1914, The Green Book Magazine, then a widely followed periodical about the American theater, published installments by Annie Adams Kiskadden, who wrote about her life as an actor in Utah and in New York City. But, the real draw of these autobiographical installments was her daughter, the more famous performer of the stage, Maude Adams. The younger Adams already had frequently graced Green Book magazine covers.

Once again, Annie had been shadowed by her more widely known daughter. The cover of the issue, which published Annie Adams’ first autobiographical installment, proclaimed “The Life Story of Maude Adams and Her Mother.” An editor’s note in the second installment (The Sweetest Story Ever Told: The Life of Maude Adams and Her Mother) read, in part, “The narrative by Maude Adams’ mother contains sidelights on America’s best loved actress, which even she could not have put into an autobiograpphy: the sort of little incidents only a mother could see and treasure.”

In a forthcoming world premiere production by Pygmalion Theatre Company, Julie Jensen’s Mother, Mother: The Many Mothers of Maude casts Annie Adams as an anti-heroine. Despite never having found even a fraction of the stage fame that her daughter had amassed, Annie stayed solid and resilient in her lifelong love of the theater, which started in her teen years during the 1860s.

Directed by Fran Pruyn, Mother, Mother will run Nov. 4-19 at the Black Box Theatre in the Rose Wagner Center for the Performing Arts. The cast represents Annie Adams; Julia, her mother; Maude, her daughter; Martha Hughes Cannon, another famous Utahn who was a physician, polygamist and the first woman in the U.S. to be elected a state senator; and five male characters – including Uncle Big (as in Brigham Young), Charles Frohman (a New York City theatrical producer) and Arthur Brown, Utah’s first U.S. senator – which are played by one actor.

Jensen, as usual, performs exemplary due diligence in researching the subjects of the play while deciding where fictional elements can flex with the historical limitations. The play covers practically Annie’s entire life, from the age of 13 to her death in the mid-1910s, when she was in her late sixties. The most extensive flex is the friendship between Annie and Martha. In Jensen’s play, they are school friends but in reality, Martha was nine years younger than Annie so it was probable only that at some point in their lives, they were familiar or had known of each other. Jensen’s decision to make Annie and Martha friends anchors the opportunity to compare their lives. Asaneth “Annie” Adams was born in Salt Lake City in 1848. Martha was born in the United Kingdom. She and her family arrived in Salt Lake City when she was four years old in 1861. “They both were influenced by the same upbringing,” Jensen explains. “But, while one got away [Annie], Martha eventually stayed and settled in Utah, married a polygamist and ended up being a polygamist herself.”

As Jensen explains in an interview with The Utah Review, while a lot is known about Maude Adams, not as much, by any measure, is available about Annie Adams. Also to capture as much historical feel for 19th century theater, Jensen adopts an iambic, quasi-formal style in the dialogue. In addition, the play clips along to fit within 90 minutes, including four acts and 17 scenes.

Jensen says the play’s episodic feel and the elevated formality of the language were part of an “experiment conducted on purpose.” She adds, “I believe it works well but I also had to make sure it works well for the actors because the lines can be hard to put in memory.” The play is filled with plenty of pithy lines, which sting and pack a good punch.

There are plenty of background details that should sound familiar to those who are casually acquainted with Utah history in the 19th century, including the church patriarchy, polygamy, the major contributions by Utah women and the prominent place that the performing arts had in Deseret. But, Jensen also shines a light on a broader topical question, which typically is not discussed publicly among those in the arts and creative communities. The stories of the successful and the most accomplished and heralded figures in the field are well known. But, what about the stories of those such as Annie Adams, who persevered despite being relegated to the shadows and wings of the theatrical world. Her love of theater never dimmed and she was always willing to take the risks and stand up again after every failure or doubt. It is worth discussing just how any creative individual deals with the fears and risks of failure and doubt in their art and craft. In that sense, Annie’s story as an anti-heroine adds generously to the historical significance which drives the play. “When I was doing my research about Annie, I searched to locate any hagiography, with the just awful dripping praise that was common during the 19th century. But there was little of that reserved for her,” Jensen adds.

Annie was ambitious in her theatrical dreams, to her mother’s dislike and skepticism. Julia also disapproved of Annie’s willingness to pin her hopes of stardom on Brigham Young, Utah’s most powerful figure as LDS president (referred to in the play as “Uncle Big”). In Annie’s recollections, which were published in The Green Book Magazine, she writes, “Brigham Young’s private carriage would be sent around each evening for all of the female performers, and always called for me.” As she recalls, her earliest experiences in professional theater were positive and promising. She quotes a note she received from one of the managers of the Salt Lake Theatre Company, which read, “You may say to Miss Adams that I hope she will continue ‘making hits’.” Annie added, “How I cherished that sentence!”

As for Maude, Annie wrote that she was certain of her daughter’s destiny on the stage. In The Green Book installment, she added, “Looking back over those years, I do not wonder that Maude was almost like a stage child. Despite my marriage and my great love for my husband, I was still wrapped up in the stage and sometimes I yearned to return to it. I was forever going to the theatre before Maude was born, almost up to the day she was born. I was continually associating with stage-folk.”

Indeed, Jensen’s script frames Annie’s story as being just as historically elucidating as her daughter’s life. Jensen also captures the differences between the two women. Annie never veered from the world of the theater. She appeared on Broadway in several productions with her daughter, periodically as members of Frohman’s New York City stock company. When she relocated from New York City back to Salt Lake City in 1908, she set up an elocution studio for students on Main Street in downtown. But, that bit of entrepreneurship also lasted barely a few years.

In writing the play, Jensen explains that she was sensitive to potential distractions which could have changed the story’s arc and character nature relating to what she focused on expressing about Annie Adams’ life. Annie had affairs but they never quite stuck, probably because she was not acknowledged as famous enough to warrant sensationalizing press coverage. Discovering the story about Annie’s affair with Brown, the Utah senator, came late in the process. Jensen added a short scene, which reinforces Annie’s own quest as an independent maverick. The scene also refers to Brown’s fears that a rival mistress will shoot and kill him, which actually happened in 1906. In the second act, Annie seeks advice from Martha, who is working as a physician, after telling her that an affair with an actor half her age had left her in ”female trouble.” Martha recommends a tin of Mrs. Chester’s “Friend to Woman,” just one example of the many contraceptive products with coded language as product names that were sold in drugstores at the time.

Maude Adams (represented in Jensen’s play, covering the ages of 13 to 40) first appeared on stage at the Salt Lake City Brigham Young Theatre when she was just two months old. Periodically, Maude returned to live with her grandmother while she pursued her education. She took a hiatus of 13 years from the stage shortly after her mother died in 1916 and in the 1920s, she worked with General Electric and the Eastman Company to help sharpen advances in stage lighting and the development of color photography. In her later years, she would become the chair of the drama program in Missouri at Stephens College.

Maude Adams had become famous for her portrayal of Peter Pan (a role facilitated by Frohman who had pursued J.M. Barrie and which Adams became the first actress to play the character on Broadway). This bit of theatrical history also is referenced in Jensen’s script. Here, as well, there is a bit of compacting down the timeline. While Maude’s GE stint and her academic career happened after her mother’s death, both are referenced in a spot of dialogue between mother and daughter.

And, as The Green Book magazine pieces indicate, Annie considered her daughter as the natural, precocious performer for the stage. “It was compelling, just how ethereally beautiful Maude was,” Jensen adds. Annie was a maverick on her own terms. But, Maude, who became famous even before she could comprehend fully what the spotlight of the stage entailed, found other points on her bandwidth spectrum to make other impacts in addition to the fame she found on the stage.

The cast includes Colleen Baum, Nicole Finney, Tamara Howell, Barb Gandy and Darryl Stamp.

The 15-day run includes performances on Thursday, Friday and Saturday at 7:30 p.m., Sunday at 2 p.m. with an extra matinee final Saturday (Nov. 19) at 2 p.m. For tickets and more information, see the Pygmalion Productions website.