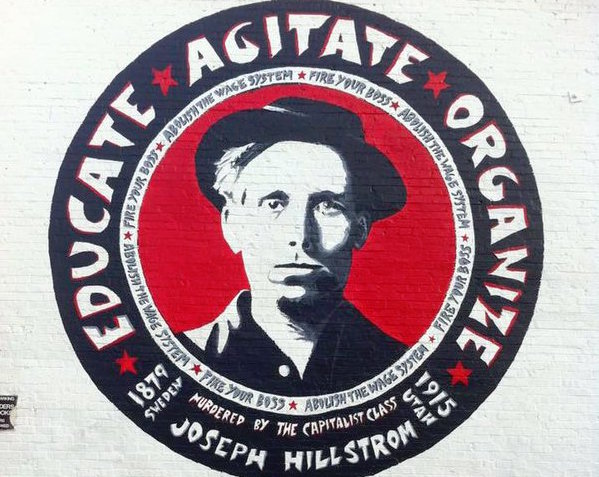

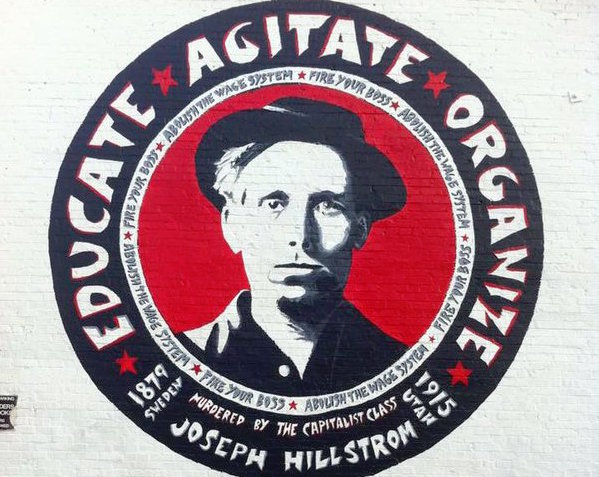

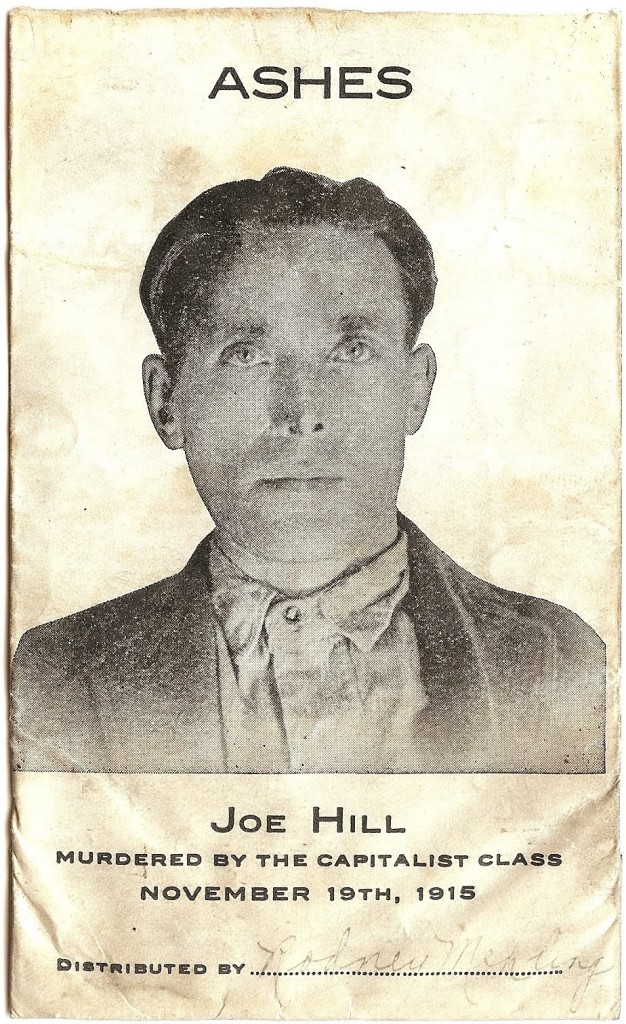

In the century since Joe Hill, the Swedish immigrant miner, musician and union activist who was executed in Salt Lake City after being wrongfully convicted of murder, there have been only a very few plays about this figure who recently has emerged from the footnotes of history in relevant ways. Last year, John McCutcheon, an American master instrumentalist, songwriter and folk musician who has carried on the traditions of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie for more than 40 years, started performing a one-man show, Joe Hill’s Last Will. The show is a meditation set in the Salt Lake City prison cell the night before Hill’s execution and draws primarily upon his songs.

In 1958, Barrie Stavis’s play The Man Who Never Died was premiered in New York City at the Jan Hus Theatre. Michael Smith, The Village Voice’s theater critic, issued a terse, savage review, calling the production “uniformly inept.” He added: “Investigation in depth is always interesting but the Wobblies [the Industrial Workers of the World or IWW] are here represented as an age-dimmed textbook labor group, and Joe Hill is distinguished only by inarticulate enthusiasm. His sole charm is a kind of supernaivete, which prompts a follower to announce, embarrassingly: ‘There was another organizer; his name was Jesus Christ.’”

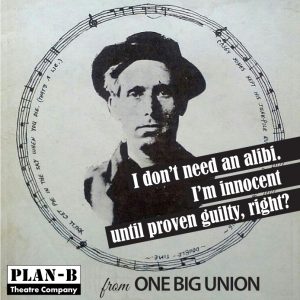

Next week, Plan-B Theatre premieres One Big Union, a play by Debora Threedy that adeptly weaves together the two most significant takeaways from Hill’s story – the egregious errors of his trial and the seminal legacy of protest songs that inspired a new way of propagating the labor movement’s political punch. The production runs Nov. 10-20 and tickets have sold out so quickly in advance that the company just added other performances in the Studio Theatre at the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts.

Indeed, One Big Union’s script indicates this could be among the best of the scores of original plays the company has ever produced. A University of Utah law professor who is retiring in December after 30 years, Threedy is the perfect playwright to give the appropriate heft to Hill’s story. One of the most passionate lovers of the stage and a significant advocate for theatrical arts, Threedy, as The Utah Review has previously acknowledged, has a strong feel for bringing historical figures and themes to the stage with credible impact as fictional treatments, thanks to deep research that highlights primary archival sources. In three previous plays for Plan-B, she earned well-deserved critical praise for stories touching variously on the lives of Everett Ruess, Wallace Stegner and the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings.

As she considers how the historical realities of her subjects demand dealing with the ambiguities and gaps in actual events, Threedy succeeds, precisely because she balances her dual intellectual passions with the right amount of paradox and irony. Gibbs Smith, who wrote and published a respected biography of Hill in 1969, asked Threedy in 2012 to take on the project of writing a play about Hill’s story, as the centenary of his 1915 execution approached. “He gave me tons of emotional support as I worked on the early drafts,” Threedy says in an interview.

One of her earliest sources at the time was the just-published book Pie in the Sky: How Joe Hill’s Lawyers Lost His Case, Got Him Shot, and Were Disbarred (iUniverse). Kenneth Lougee, a long-time trial lawyer with the Siegfried and Jensen firm, examined the legal proceedings leading to Hill’s conviction for the murder of John G. Morrison, a Salt Lake City grocer and former police officer, and his son, Arling.

The prosecution’s case was based on one piece of circumstantial evidence: Hill suffered a gunshot wound to the chest on the same night — Jan. 10, 1914 – that the murders occurred. Prosecutors were convinced that he was shot by one of the victims during a botched robbery.

Lougee did not focus on the issue of Hill’s innocence but he also emphasizes the Utah Supreme Court to this day still accepts the legal merits of the appeals decision that ultimately cleared the way for Hill’s execution at the age of 36.

At about the same time, William Adler had his book, The Man Who Never Died: The Life, Times, and Legacy of Joe Hill, American Labor Icon (Bloomsbury USA), published that further questioned the circumstantial evidence upon which the activist had been convicted. Adler produced a letter by Hill’s former girlfriend, Hilda Erickson, in which she wrote that Hill told her he had been shot by her former fiancé, Otto Appelquist. Neither Hill nor Erickson testified at the trial and many assumed that Hill, who contended that he did not have to prove his innocence, wanted to protect the young woman’s identity. While Adler presented the letter as the strongest evidence of Hill’s insistence that there was some other gunman involved (apparently the only person Hill ever said anything about how he was shot to was the physician treating his gunshot wounds), he also stopped short of exonerating Hill in the case.

Likewise, Threedy treads judiciously on the question. While Hill’s descendants were thrilled to hear about Adler’s findings, John Arling Morrison, the grandson of the murderer grocer, said in a 2011 New York Times interview, “Joe Hill was the one who murdered our grandfather and destroyed the economy of our family.”

Hill is labor’s version of Don Quixote. He is adamant and absolute. In the play, he tells Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an Irish firebrand activist, that it would be “senseless to drain the whole organization for just one individual.” She responds, “I don’t agree. The union is made up of individuals, and every one of us is just as important to the cause as anyone else. You’re not thinking about becoming a martyr are you?” He says no but she asks, “Then why don’t you save yourself?”

At this point, Hill’s only option is a pardon but he refuses: “They want me to beg for my life real nice and if I do, maybe they’ll commute my sentence to life. Life imprisonment. Life sitting in this rathole.” Hill may say that he has no desire to be a martyr but, as one character states, “To the IWW Joe Hill is a hero and a martyr. Hill dead is going to be much more dangerous than he was alive.”

Threedy also casts a character called the Working Stiff, a union ‘Everyman’ who serves as the chorus of the play, providing colorful details about the trial and about the Wobblies. Early in the play, he says,

McHugh turned Joe into the cops for 500 hundred pieces of silver instead of thirty – that’s inflation for you. And thirty four years later, he added the small little detail that Joe actually confessed to him – but he never told the cops about Joe’s supposed confession and he never mentioned it in his two times on the witness stand. He also claimed Joe said it was a robbery gone bad – but as we’ll see, the murders were no robbery, they were revenge killings.

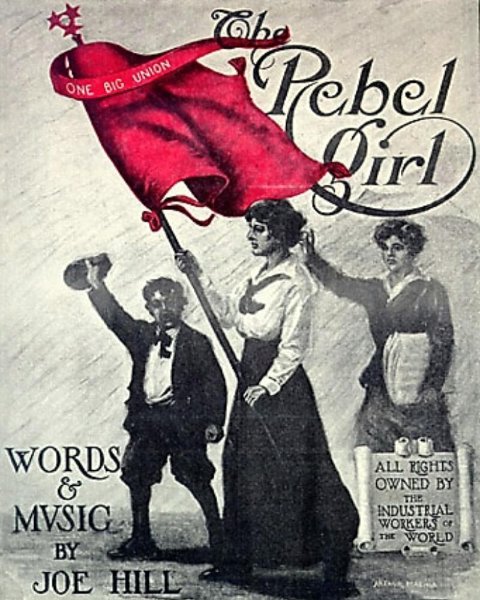

In Threedy’s play, the counterpoint to the trial’s legal rhetoric and Hill’s impassioned pleas and frustrations comes in the songs that define the Wobblies (IWW). They are critical markers in the intricate narrative she has established in the script, whether they are part of a particular scene, supplement the narrative as a comment, or serve the logistical function of a scene change. The songs reinforce the play’s feel of one big union hall.

Nearly all of the songs and lyrics were written by Hill with significant exceptions: The Red Flag, a Wobbly recruitment hymn that was sung at Hill’s funeral, and Joe Hill’s Last Will with melody by Marv Hamilton.

Music was integral to the union movement’s appeal. The IWW rapidly expanded in the early 20th century with the goal of a sufficiently broad enough movement to mount a general strike for worker’s rights. Initially, the union had used revolutionary songs from Europe but Hill, most prominently, demonstrated that new songs could hit the right relevant notes with an American public. The form of song fortified the union manifesto’s message, noteworthy because it had the potential of spreading its appeal quickly. It would be another decade at least before radio would emerge and the gramophone only then was becoming a more widely used way to enjoy music. Dard Neuman, a scholar specializing in cross-cultural musicology, quoted Hill:

A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read but once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over. And I maintain that if a person can put a few cold common sense facts in a song, and dress them up in a cloak of humor to take the dryness off of them he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent to too indifferent to read a pamphlet or an editorial on economic science.

Hill’s songs are effective because of their adaptability. There is no musical necessity of a single definitive interpretation, as some Joe Hill purists might argue. Folk music is inherently malleable. Whether a Hill song is interpreted as a gospel, vaudeville, bluegrass, ballad, ragtime or march tune, the integrity of the lyrics is never compromised.

A good example, as Neuman cites, is Hill’s Casey Jones, the Union Scab, which he reworked from The Ballad of Casey Jones, a song credited to an Ohio railroad employee who wanted to pay tribute to an engineer who died in a railroad accident (not ironically a martyr). In Hill’s version, the “brave engineer” becomes the stark opposite of the union scab who ends up in hell “shoveling sulphur” for the Devil because “that’s what you get for scabbing on the S.P. Line.”

Hill’s songs, as Neuman explains, flipped the expected logic of the original form. One initially might believe The Preacher and The Slave (based on the religious hymn The Sweet Bye and Bye) as a spiritual to lift the yearnings of listeners to shake off desperation and isolation. Instead, Hill’s version energizes the political impulses, making the union hall – the movement’s incubator – come alive with vibrant activism.

Forget genteel civility that often is propelled by self-righteous piety, and one glimpses the social climate of the provocative, tense, unsettling relationship between labor activists and perhaps staunchly religious activists (as some Mormons at the time were still sensitive to the basic broad issue of collectivism and solidarity that marked their first decades in Utah). The song’s final stanzas close:

Workingmen of all countries, unite,

Side by side we for freedom will fight;

When the world and its wealth we have gained

To the grafters we’ll sing this refrain:

You will eat, bye and bye,

When you’ve learned how to cook and to fry.

Chop some wood, ’twill do you good,

And you’ll eat in the sweet bye and bye.

Directed by Jason Bowcutt, the play was work-shopped at the Utah Shakespeare Festival’s New American Playwrights Project. Bowcutt says he has appreciated Threedy’s willingness to make changes. Initially, Threedy suggested the primary setting – nonrepresentational as the scenes suggest many different locations — should be the “looming presence” of a prison and the confines of Hill’s cell. Bowcutt sets the stage as a union hall – with an IWW flag and workbenches. The cast ensemble is on stage at all times and the setting underscores that the play is not a musical but as a play with songs and musical skits, as Threedy has crafted.

The 80-minute production features four men and two women in the cast: Roger Dunbar (as Joe Hill), Daniel Beecher, Carleton Bluford, April Fossen, Tracie Merrill and Jay Perry. David Evanoff directs the music and Stephanie Howell is choreographer. Other production crew members include Keven Myhre (set design), Jesse Portillo (lighting) and Aaron Swenson (costumes).

A benefit performance for the Entrada Institute also is slated for Nov. 9 at 7 p.m. For more information, see here.

Ticket availability is limited, as many performances already have sold out houses. Performances are slated for Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays at 8 p.m., Saturdays at 4 p.m., and Sundays at 2 p.m. and 5:30 p.m. A pre-paid wait list will begin one hour before the posted show time in the Rose Wagner box office. Patrons must be present, in person, to be added to the list. At show time, as many patrons as possible from the wait list will be seated in any empty seats (Plan-B maintains a no-late seating policy that makes the wait list possible). If patrons are unable to be seated they will receive a full refund immediately.

Ticket availability is limited, as many performances already have sold out houses. Performances are slated for Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays at 8 p.m., Saturdays at 4 p.m., and Sundays at 2 p.m. and 5:30 p.m. A pre-paid wait list will begin one hour before the posted show time in the Rose Wagner box office. Patrons must be present, in person, to be added to the list. At show time, as many patrons as possible from the wait list will be seated in any empty seats (Plan-B maintains a no-late seating policy that makes the wait list possible). If patrons are unable to be seated they will receive a full refund immediately.

The University of Utah’s Marriott Library also will present a two-part lecture series (free) about Joe Hill, led by The Salt Lake Tribune’s Jeremy Harmon, on Nov. 4 and Nov. 14. For details, see here and here.

The production also is sponsored by The George B. & Oma E. Wilcox and Gibbs M. & Catherine W. Smith Charitable Foundations.

For information about tickets and the production, see here.

1 thought on “Plan-B Theatre’s newest production One Big Union highlights Joe Hill, Wobblies”