‘Having spent much of the past three years reading and writing about this subject, I wonder whether it is even worth engaging with these arguments. The aversion to government spending, and government activity generally, which animates many Americans isn’t actually based on economics, or logic: it is an emotionally driven belief system, founded upon a cockeyed view of American history and buttressed by a variety of right-wing shibboleths.’ – John Cassidy, The New Yorker magazine, June 4, 2012

If one is to believe the chattering class of political pundits, the debate about the nation’s economic affairs almost always turns on the clash between the Keynesians, represented by John Maynard Keynes, and the free market disciples, as epitomized by Friedrich August Hayek.

The reality, according to many historians and economists, is quite different. As John Cassidy explains, ‘the real policy debate isn’t about Keynesianism versus the free market, it is about magnitudes and techniques: How much stimulus is necessary? And how should it be divided between government spending and tax cuts?’ To wit: the latest Gallup poll in which nearly one of four Americans believes unemployment to be the nation’s biggest problem, a finding that appears in responses among the three major political affiliations (Republican, Democratic, Independent).

The reality, according to many historians and economists, is quite different. As John Cassidy explains, ‘the real policy debate isn’t about Keynesianism versus the free market, it is about magnitudes and techniques: How much stimulus is necessary? And how should it be divided between government spending and tax cuts?’ To wit: the latest Gallup poll in which nearly one of four Americans believes unemployment to be the nation’s biggest problem, a finding that appears in responses among the three major political affiliations (Republican, Democratic, Independent).

In fact, much of the discussion about economics often does seem to be nothing more than a ‘load of bollocks,’ a sentiment uttered a few times in Eric Samuelsen’s new play ‘Clearing Bombs,’ which he also will direct in a premiere Plan-B Theatre production which begins Feb. 20. The play starts from an actual instance from 1942 when Keynes, then 59, and Hayek, then 41, – both among the most simultaneously celebrated and vilified macroeconomists of the twentieth century – spent the night together on the roof of the King College’s Chapel at Cambridge with the duty of chasing and clearing German bombs that might land.

In imagining the night-long discussion both economists might have had, Samuelsen adds Mr. Bowles, a third character, a sort of an Everyman who serves most effectively to shape the thoughtful intelligent dialogue with a genuinely pragmatic and human consideration provoking what a real picture of economic justice and equality could be. Bowles is a fire warden in his fifties who is thoroughly proud and comfortable as a middle-class member of British society. At one point, Bowles echoes a realistically common sentiment:

‘It’s all a lot of words. Big words, to confuse us. Every day in the papers, it’s the same; “economists say . . .” Prices will rise, or not, joblessness improves, or it doesn’t. You’re in the predicting business, you are, your science says what will happen in future. And you don’t know, any more than we can trust the bloke who predicts the weather, any more than I’ll know if a bomb hits us, before it does. We’re here, on a building housing children, about to be bombed. That’s what’s real. It’s got naught to do with economics.’

‘Clearing Bombs,’ the third of four Samuelsen plays being premiered in Plan-B’s ‘Season of Eric,’ meets and satisfies several formidable challenges. A surely difficult play to write, especially in the challenge of making the subject material enjoyable and comprehensible to even an audience member who would have avoided with effort even the notion of taking a basic course in economics, the script is approachable in a pleasantly satisfying, lucid way.

Similarly, while many of Plan-B’s original works have formed a canon of intelligent, articulate works about social justice that most effectively tug at authentic human emotions, ‘Clearing Bombs’ is a different work, focusing most intensely on the issue of economic justice. ‘I think economic justice is essential for social justice to occur,’ Samuelsen explains. ‘All the problems we can see in America today having to do with poverty and the difficulties of the underclass seem to me more economic than social. Or at least, social issues have a significant economic component. And obviously income inequality is entirely economic.’

However, the most essential core of ‘Clearing Bombs’ is less rooted in economics, a subject the playwright generally avoided during his schooling. The play instead feeds upon the dramatic contrasts of intellectual thought and process as epitomized by two of the most dynamic personalities to dominate in their chosen field of work. ‘As a playwright, I’m drawn to intelligent people with forceful personalities who strongly and powerfully disagree about important things,’ Samuelsen says. ‘When I first read about the rooftop night Keynes and Hayek shared in 1942, I was immediately attracted to the dramatic possibilities of it; just two guys on a roof.’ The third character, Mr. Bowles, ‘seemed like an immediate necessity, because left to their own devices,’ he adds. ‘I assumed that two macroeconomists would just use the jargon of their field, and that audiences wouldn’t have the faintest notion what they were saying.’

However, ‘Clearing Bombs’ also needed the right touch of economics material. Samuelsen always is scrupulous about background research to bring a believable frame to plays situated in historic periods and personalities. For this work, he was inspired by Nicholas Wapshott’s 2011 book ‘Keynes Hayek: the Clash that Defined Modern Economics.’

Many of the questions raised in ‘Clearing Bombs’ – and the reactions and responses articulated especially by Mr. Bowles the Everyman character – go to the most fundamental issues raised in Wapshott’s book. ‘The debate between these two guys in the Forties provides the blueprint for economic debates today,’ Samuelsen explains. ‘Keynes Hayek could well be Obama Romney, or Clinton Bush. Or, more accurately, the debate today is over the combination state–half free markets, with a strong social safety net–Norway, Denmark, Germany, France, to some extent Great Britain today–vs. libertarianism (which is where the real intellectual energy is today on the right). ‘

Samuelsen’s preparation, indeed, would bring a smile to even the sternest professor of economics. He supplemented Wapshott’s works with biographies about both economists, his son’s textbook for an undergraduate economics course, an extensive list of writings by Keynes and Hayek, works by Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong, and others. ‘I got in the habit of reading The Wall Street Journal and Paul Krugman’s blog every morning. And then I’d get into fights with libertarians on the Internet, and they’d always say “have you read this?” and usually I hadn’t, so I would,’ Samuelsen recalls. ‘I also love ‘The Worldly Philosophers’ by Robert Heilbroner. I wish I could say I read systematically, starting with Adam Smith and working my way through Malthus and Ricardo and so on, but I didn’t. I did read most of Wealth of Nations, but dang! Dense. ‘

Audience members will appreciate Samuelsen’s treatment which gently directs them toward becoming comfortable in unfamiliar territory. It is more than 10 minutes into the play before even anything related to economics is mentioned. We hear Hayek grumble about the forthcoming night’s assignment: ‘Of all the unlikely faculty assignments. . . you are expected to tutor, to lecture on occasion perhaps, to research and publish, and from time to time, spend a night on the rooftops of the buildings to prevent them being destroyed by incendiary bombs.’ We also get a sense of Keynes’ deep Eton pride. Meanwhile, Bowles outlines the blackout rules.

The mutually respectful tone among the men is often punctuated by incisive remarks rightly stirring up the dramatic tension. Here, economics is neither a dismal science nor the polite bailiwick of intelligent policy wonks. Hayek at one point clearly shows his displeasure, mentioning war loans being arranged by Keynes. It is Bowles who asks Hayek, ‘and you, Mr. Hayek? What’s your part?’ Hayek, visibly embarrassed, responds, ‘Well. I . . . teach.’

With smart irony, Keynes briefly helps out Hayek by explaining to Bowles his work. ‘And it’s an important book, Mr. Bowles. What happens after the war? How we should proceed. Economically. ‘The Road to Serfdom’ [a book which came out two years later, in 1944]. Keynes adds, ‘Don’t get me wrong, Freddy. It’s passionately written. I simply lack your attraction for . . . tragic inevitability.’

When writing about history, Samuelsen has a nice gift for erudition writ large, letting all three characters fill in the portrait of the economic issues that defined the landscape of the time. One of the most interesting bits comes in the first half hour, when Keynes talks to Bowles about the real prominence of economic principles in election campaigns:

‘You are voting for a set of economic principles. You are voting for one of several competing economic theories, each with its own policies and programme. And if you vote foolishly, if you vote for a theory that is wrong, that inadequately describes the world, that attributes to human beings behaviors they do not engage in, or inadequately accounts for behaviors we do in fact engage in, if you vote the wrong way, for the agreeable chap you could imagine sharing a pint with, but who, as it happens, believes in a bad theory, an unworkable theory, a chap who will, if elected, attempt to implement a foolish economic programme based on an untenable theory, you could, in very short order, drive your nation off a cliff into disaster.’

Passages like these create the relevant context for today’s audiences who see the same debate being played out constantly in the daily news. ‘I was fascinated by Keynes’ idea (often expressed) that elections aren’t really about personalities or even parties; they’re about competing economic theories,’ Samuelsen adds.

Bowles also serves quite effectively to give the hands-on perspective clarifying the jargon uttered by his two compatriots on the chapel rooftop. He mentions day laborers, the decision to buy milk or meat, discreet gestures of charity at the local parish, and potato patches in the yard. ‘So when Keynes and Hayek are explaining basic economic principles to Mr. Bowles, I could rely on my memory of my son doing the same for me,’ Samuelsen adds. ‘I’m essentially Mr. Bowles. So that was the approach I took–I’d figure out these ideas, and then I’d explain to my old self.’

Concepts such as Hayek’s ‘natural state of equilibrium’ become understandable in a pleasant, even humorous, way. We know that Bowles would never choose a speculative venture not knowing the magnitude of the risk involved – ‘The wife. She’d take my head off.’ However, his brother-in-law is a confident entrepreneur, ready to recoup his investment in pigs by making it ‘back in bacon.’

Samuelsen turns to ‘bad coffee, overcooked vegetable mush, horrid little meats, washed down with warm beer’ to help explain Keynes’ idea of incessant sub-optimal equilibria. ‘I remembered some ghastly meals from my time in London, when I was running a Study Abroad program. And I thought: “British food! It’s sub-optimal (it’s rubbish, actually), but it exists because supply and demand are perfectly balanced,’ he adds. ‘So that joke made its way into the play.’

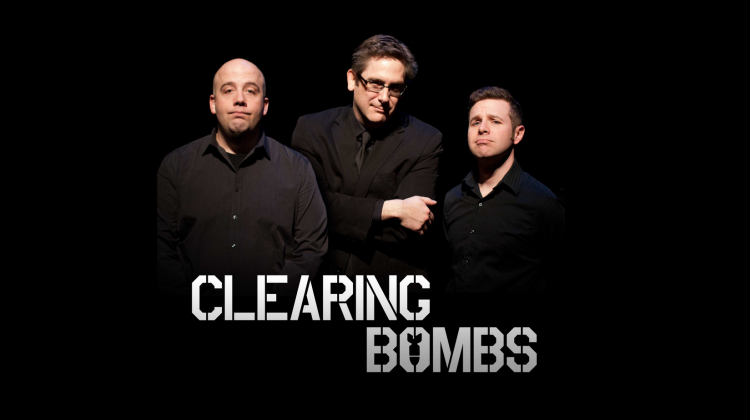

The three-actor cast features strong popular veterans. Jay Perry plays Hayek, Mark Fossen takes on the role of Keynes, and Kirt Bateman takes on duty as Bowles. There are important nuances to be considered. Keynes was in the last years of his life, dealing with a debilitating illness at the time of the play’s setting. ‘I’ve written him as a man who knows he hasn’t much longer to live,’ Samuelsen says, ‘and Keynes had a marvelous speaking voice, as does Mark; he gets some of the most soaring oratory in the play, which plays to Mark’s strengths as an actor.’

Perry’s challenge is to overcome what Samuelsen describes as a conundrum in the Hayek portrayal. ‘Hayek wrote beautiful English prose, but spoke with a pronounced German accent. Jay’s [Perry] approach has been to stress Hayek’s ideas and thoughts, and really make them soar, while still remaining comprehensible,’ he adds.

As for Bateman’s role, Samuelsen explains that a ‘significant challenge is making Mr. Bowles an intelligent man. He doesn’t understand macroeconomic jargon, but he’s not a dummy. But when someone is going “I don’t understand. . . .” all the way through, the danger is that he’s going to appear less smart than he is.’

Performances of the 90-minute play continue through March 2 in the Studio Theatre at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center. Times are Thursdays and Fridays at 8 p.m.; Saturdays at 4 p.m. and 8 p.m., and Sundays at 2 p.m. Tickets are $20 with discount admission available for students at $10.

The play also is supported by an ArtWorks grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. For more information, see http://planbtheatre.org.

1 thought on “Plan-B Theatre’s ‘Clearing Bombs’ seeks to bring sense to the clash of economic principles”