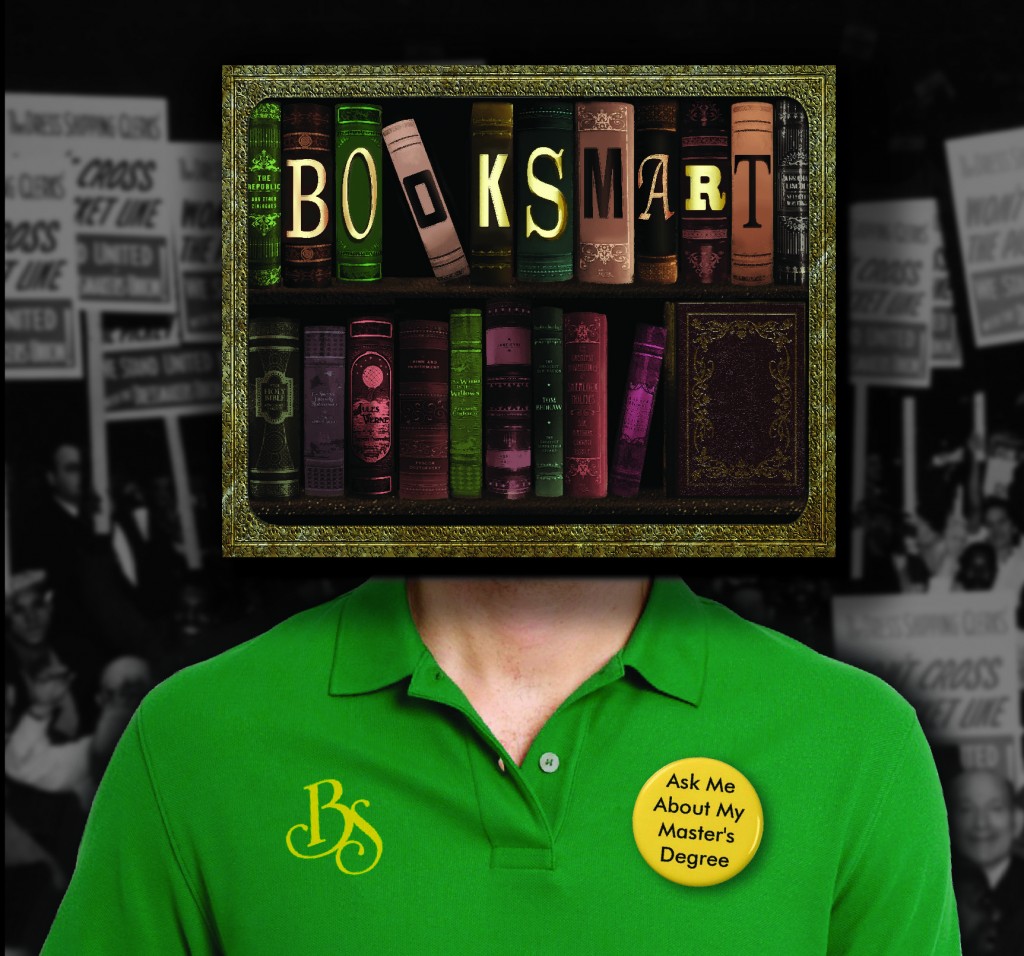

In last year’s Plan-B Theatre production of Julie Jensen’s Christmas with Misfits, the stage overflowed in an mini avalanche of cheap, gaudy, motley Christmas decorations including the memorable ‘Baby Jesus Collection’ display created by local steampunk artist Arika Schockmel. In Booksmart, this year’s holiday season offering by Plan-B, the employee breakroom is haplessly drab.

Plan-B is good at staging unconventional holiday season productions. For Booksmart, a Christmas tree is still in its box. The overworked, underpaid, insufficiently appreciated, emotionally exhausted employees of this fictional big box book retailer (appropriately abbreviated as BS) have no intentions of finishing the holiday décor. It represents the meager confines where they escape during yet another frustrating day on the store floor dealing with shoppers who are hardly empathetic to store employees. The breakroom is a space to commiserate about the difficulties of making ends meet, with wages and salaries that are modest at best and barely cover living expenses or the college debt that comes with the higher education experience.

Plan-B is good at staging unconventional holiday season productions. For Booksmart, a Christmas tree is still in its box. The overworked, underpaid, insufficiently appreciated, emotionally exhausted employees of this fictional big box book retailer (appropriately abbreviated as BS) have no intentions of finishing the holiday décor. It represents the meager confines where they escape during yet another frustrating day on the store floor dealing with shoppers who are hardly empathetic to store employees. The breakroom is a space to commiserate about the difficulties of making ends meet, with wages and salaries that are modest at best and barely cover living expenses or the college debt that comes with the higher education experience.

However like Jensen’s work which was a dark comedy with some encouraging moments of redemption, Booksmart, the debut work of playwright Rob Tennant, follows a similar vein. Nicely couched in the comedy, Tennant makes Booksmart into a realistic social commentary about the stunted hopes and aspirations of college-educated individuals who thought their degrees would lead them to far more exciting paths than being on the frequently brutal front lines of customer service in a big box retailer.

And like Carleton Bluford’s Mama which Plan-B staged last season, Tennant’s play was selected unanimously in a blind reading process involving 24 submissions from Utah-based playwrights 35 and younger in the inaugural competition for the David Ross Fetzer Foundation for Emerging Artists (The Davey Foundation).

Tennant’s play features five characters who work for the fictional book retailer Booksmart and any resemblances to actual retailers are situated in the author’s own experience. A journalist-cum-marketing and communications coordinator, Tennant’s time in customer service included stints as a restaurant waiter and as an employee for a Barnes and Noble store. The characters are composites of others with whom Tennant worked.

The idea for Booksmart had been germinating for more than 13 years. He originally had planned a web-based series but the time did not seem conducive to drawing viewers who would want to, in Tennant’s words, “care about these people.”

The zeitgeist surrounding Tennant’s play became acutely apparent especially after the deep recession. And, as this year’s holiday shopping season swings into full motion, even with unemployment at a seven-year low, the demand for seasonal employment is greater than ever. Holiday season jobs were once the primary domain for housewives and college students but now millions of workers – including those with college degrees or in professional occupations –do not hesitate to grab the seasonal jobs for supplemental income.

Tennant, who deftly uses humor to negate even the slightest suggestion that the play is preaching a specific socioeconomic message, says Booksmart naturally “ends up on the serious issues.” He adds, “that it still is difficult to imagine that one day we would be thinking that a bachelor’s degree could become meaningless for finding the right job.”

And, as Jerry Rapier, Plan-B’s director explains, the play encapsulates just how we came to accept “30 as the new 20.” There is Casey, who is in his mid-twenties, the organizer of a work stoppage. His predicament is probably a familiar for many others in his generation:

And, as Jerry Rapier, Plan-B’s director explains, the play encapsulates just how we came to accept “30 as the new 20.” There is Casey, who is in his mid-twenties, the organizer of a work stoppage. His predicament is probably a familiar for many others in his generation:

I’ve worked my entire life. I worked this job as close to full time as allowed by corporate policy while college was also full time and when I was done this was the only job left. But now I have a mountain of debt because working while in school wasn’t enough to pay as I went, just barely enough to keep me alive and sheltered. And that, my friends, is completely fucked.

At first, Casey’s efforts to recruit his colleagues are met with more amusement than any serious consideration. Casey hopes that he can convince his colleagues to make a stand against the boss during the busiest time of the season. At one point, he tells Ruth, an artist in her late 40s who is in the midst of a second career and has suffered the injustices of not being fully appreciated as a college adjunct instructor, that he is on strike. “We deserve more than this. I want you to help me achieve that better, brighter world you strove for in your youth.” She responds, “Aren’t you just adorable?”

The others are hardly persuaded by Casey’s intentions. At first, one gets the sense that Casey’s enthusiasm is running a bit ahead of his intelligence or capacity to work out the finer points of his mission. But, as the play moves forward, Casey’s sincerity carries him through admirably. Indeed, he is smarter than what others might see in him. It’s just that he has yet to fully articulate what the demands should be for this protest. In one scene, he tells the others, with sincere gravity: “Better working conditions. Higher pay. Stuff like that.”

Far more mature and more cynical, Alex is the same age but she is definitely skeptical about Casey’s tactics. On this particular day, Casey has yet to do one bit of work and has instead parked himself in the break room. Rattling off a list of possible duties, Alex reminds Casey, who has spent some of the time browsing his Facebook account, “Well, those things are our job. If you haven’t been doing them, what have you done? It’s crazy out there. It’s the week before Christmas.” Casey responds: “I’m not just on Facebook. I have news and books and stuff on here, too. As for snacks, I have to keep up my strength. For the struggle.”

Tennant nicely rounds out the personality tones in the cast of characters with Cindy, the youngest employee, who is cheerful but also intelligent, and Ed, a bona fide older generation hippie. Tennant describes Cindy as “a trendy geek-chic nerd girl who likes comics and video games, though probably not the ones you like.” There also is a sixth character who is never seen but heard over the store intercom. Tim is eternally overwhelmed and needs assistance to handle tense, impatient customers.

The fictional scene is filled with many evident truths. Ruth is resigned to making ends meet over fighting battles along lines of principles. Alex is charmed generally by Casey, whom she calls a “sexy revolutionary.” Casey’s idealism is as charming. He tells Ruth, “I want you to help me achieve that better, brighter world you strove for in your youth.”

The others gradually take Casey’s words with more seriousness. In 85 words, he sounds near-eloquent in explaining how they have become the latter-day proletariat:

The others gradually take Casey’s words with more seriousness. In 85 words, he sounds near-eloquent in explaining how they have become the latter-day proletariat:

We’re the latter-day proletariat. What’s left of blue-collar labor is a cushy gig these days, you know, what hasn’t been shipped overseas or replaced by robots. Auto workers and steel workers and, I don’t know, dock workers, have boats and way too many guns and big trucks they helped build and dental insurance, and they come in here to buy magazines with their trucks and guns on the covers from my nine-fiddy-an-hour ass. This is about class, ladies, and everyone in this room is on the bottom rung.

Art more than imitates life, especially for the actors who are portraying characters of their same generation. Tyson Baker, a 30-year-old actor who works at a deli while trying to finish his college degree in acting and directing and hoping to find time to write his own play, portrays Casey. He writes:

The smell of deli food and canola oil permeate from my triple-worn jeans and work uniforms fills my fifteen-by-fifteen bedroom I rent in a duplex with my buddies from college. It leaves a dull, musky, boyish scent about the place. My room is a clutter catastrophe of messy stacks of plays, dirty laundry, fantasy novels, Dungeons & Dragons, tip money clumps, old college textbooks, month-old socks, dressers akimbo, unhung posters and portraits, and most importantly, a pillowed queen-sized mattress for the purpose of burrowing my being. My head is a big balloon full of mostly hot air and a brain swishing around in there somewhere with thoughts and dreams and fears, all swimming.

In addition to Baker, the cast includes Anne Brings, Joe Crnich, April Fossen and Sarah Young. With several phone calls from customers inserted throughout the play, Cheryl Ann Cluff is adding her usual sound design touches that will include the playing of Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer with irritating frequency.

For more information on tickets, see here.