In Oda Might, a new play by Camille Washington, the patient, a middle-aged black woman in a psychiatric hospital, relates details of her life to her doctor, also a black woman but younger and lighter skin. The patient, a spiritual medium who believes she is the scapegoat for a murder, is candid about her life as a hustler. She talks about how she had relapsed into her hustling ways after a period of “faith, or institutional recuperation.” She explains, “And since I lost God’s favor. Again. I got back into forging checks almost immediately. Stealing checkbooks during readings and using them to put money into an account for when I came back to New York.” She admits her actions and her running away were selfish: “I figured I didn’t deserve the comfort and stability of a straight life.”

The doctor tells the patient that there are no signs of schizophrenia, paranoia, or borderline personality disorder, adding that she finds her candor and lucidity refreshing. A bit agitated by the doctor’s words, the patient responds, “What you people do with this information is on you. I should not be here but no lie I could make up will change the fact that I am. Even if I had the best lawyer on earth I’d probably still be here.”

It is a crucial scene early in Washington’s script, which is filled with many moments of foreshadowing. Structured in a traditional narrative frame, nevertheless the playwright sets the storyline on a simmer that eventually boils into a shocking thriller. Oda Might will receive its world premiere by Plan-B Theatre, in a production run that begins Nov. 7 in the Studio Theatre of the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. Explaining that she is taking a gentle approach given what the epiphany will reveal, Cheryl Ann Cluff, who is directing the premiere, adds, “It should just feel like a rather interesting discussion between a patient and psychiatrist.”

Oda Might’s premiere is momentous for several reasons. It is the fifth and final world premiere that Plan-B committed to in its partnership with The David Ross Fetzer Foundation for Emerging Artists. Washington’s play was chosen from among a dozen juried submissions by writers 35 and younger. The decision to greenlight Washington’s play was not by a close margin, according to Jerry Rapier, Plan-B’s artistic director. For example, in a jury that included among its members the two most recent winners (Morag Shepherd, Not One Drop, and Austin Archer, Jump), they joined Rapier in ranking Oda Might in first place.

In a community and state, where it has been primarily the efforts of small independent theatrical companies to produce plays by artists of color that resist and demolish the tendencies that have controlled and regulated the placement of black characters and their images, Oda Might is an exceptional addition to Plan-B’s growing canon of new works that exemplify inclusion and diversity on an unparalleled scale regionally.

Washington originally intended to set the play as an exploration of religion, mysticism and spirituality among black women. Then, in learning the details of a news story from Dearborn Heights, Michigan six years ago, she wanted to expand the thematic horizons. Renisha McBride, 19, was involved in an early morning auto accident and she went to a home where a white man, believing she was an intruder, shot and killed her with a shotgun through a porch screen door. The man testified that he feared for his life while prosecutors noted that while McBride was intoxicated the man did not need to use deadly force. Despite the conviction, sympathizers of the man shared information on social media emphasizing McBride’s blood alcohol content level, in trying to make the case that the man was innocent because of reasons of self-defense.

McBride’s death came early in the Black Lives Matter movement but the concept of respectability politics already had sprouted its viral roots long before the arrival of social media. In 2000, Patrick Dorismond, a Haitian immigrant was shot and killed by New York City police officers. At a press conference, Rudy Giuliani, then mayor, said the young man was not an “altar boy,” trying to make the case by releasing his juvenile arrest record. The irony was that Dorismond had been an altar boy. His grieving mother aptly described the phenomenon in a cable television interview, “They kill, and after that, they kill him the other way — with the mouth.”

It is significant that Washington sets the play in the early 1990s, “certainly no later than 1994.” In 1989, it was Donald Trump who took out a full-page newspaper ad with the all-caps headline “BRING BACK THE DEATH PENALTY. BRING BACK OUR POLICE!,” urging capital punishment for the Central Park Five, who were charged with the rape of a jogger. All five individuals were later exonerated and the city settled with the men for a total of $40 million, a settlement that Trump also publicly disputed.

Indeed, Oda Might is framed as a timely and timeless piece. In explaining the rise of the dual images that many black people posted with the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown after Michael Brown’s murder in 2014, Adam Serwer explained, “The dual images posted by Twitter users are provocations, challenging observers to wonder if they could spot the Marine or college graduate if they first saw them clad in a hoodie or enjoying a drink. Core to the meme is resisting the concept of ‘respectability politics,’ the idea that defying superficial racial expectations can shield minorities from discrimination. The pictures remind us that no one can – or should have to be –‘respectable’ all of the time.”

This anchors the underlying context for Washington’s superb script. “I want to see very talented groups of actors perform stories with ambiguities of truth and reality,” Washington, who has produced and directed numerous works in Ogden with her sister, says. “This is a complicated, messy story and it is presented as subtly subversive.”

Cluff, in an email response, says, “It’s been interesting to talk about what elements in the play are real and what elements are not real and are only in the mind of DOCTOR. And can PATIENT see or sense any of the things DOCTOR sees/hears and how does it impact PATIENT, knowing she’s a medium.”

At the outset, for the audience’s benefit, Washington clearly tees up the listening and response dynamics between the doctor and the patient. An orderly also appears sporadically, in the first scene which encompasses almost two-thirds of the play. In the remainder of the play, she appears more frequently. In some moments, the patient ignores what the doctor says and abruptly switches the focus. However, interspersed with the tense moments of defensive posturing from the doctor as well as the patient, there also are many indicators how both are equal partners in navigating and negotiating what and whose truth really matters.

For the most attentive, astute listener in the audience, the reward comes later in the play. To say anymore would be a deep injustice to the magnificent writing Washington has imbued throughout the story of Oda Might. The characters in the play are not prefigured to the inherent norms and limitations that dominate many segments of Utah’s theatrical activity and discourse, especially when so many prior roles have emerged from problematic and all-too-familiar black archetypes.

“In rehearsal we’ve talked more about the layers and multiple meaning behind lines in this play – probably more than I have in any other play I’ve directed for Plan-B,” Cluff writes in an email response. “We talked and TALKED AND TALKED about the layers early on – really heavily during the first week of rehearsal, and then we left those discussions and let the hints of those layers be there in the work instead of spoon feeding them to the audience.”

Cluff, who has selected music and designed sound for many Plan-B productions, says she and Washington decided on a stark mood for Oda Might. “I’m using ambient sound of a mental hospital (echo-ey voices and footsteps) for preshow and during the scene change to help establish the bleak environment,” Cluff adds.

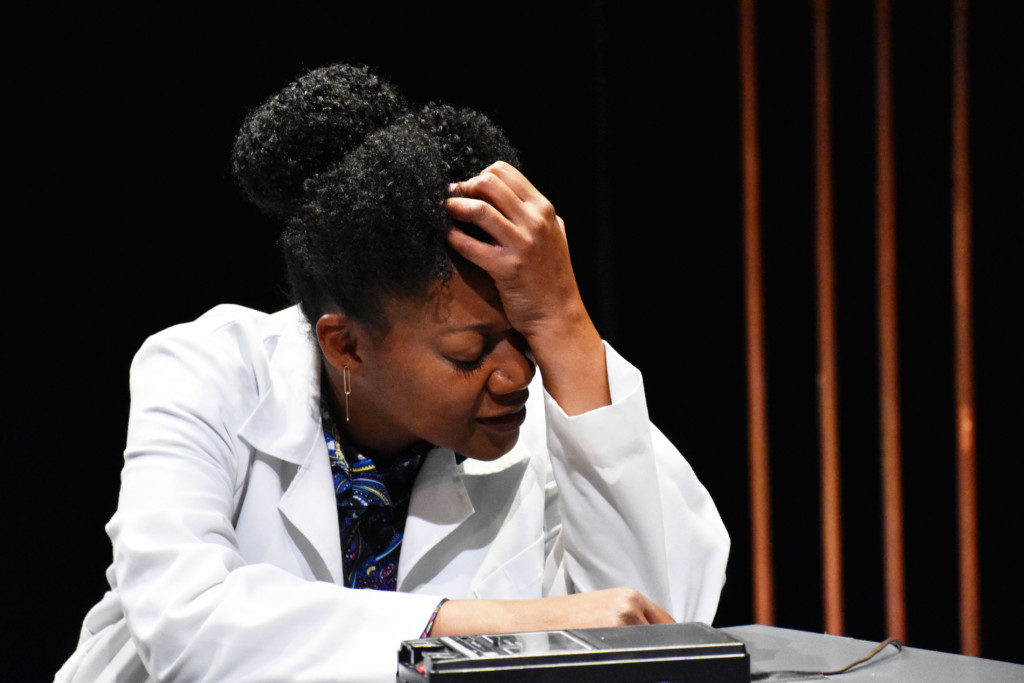

The cast includes Dee-Dee Darby-Duffin as the patient, Yolanda Stange as the doctor and Flo Bravo as the orderly. Sam Allen is assistant director. Rounding out the production crew is Kevin Alberts, costume designer; Jennifer Freed, stage manager; Keven Myhre, set designer and William Peterson, lighting designer.

Performances, which run Nov. 7-Nov. 17, are scheduled on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays at 8 p.m., Saturdays at 4 p.m. and Sundays at 2 p.m. For tickets, which are going quickly, see the Plan-B website.