The great French philosopher Paul Ricoeur wrote that forgetting “remains the disturbing threat that lurks in the background of the phenomenology of memory and the epistemology of history.” Nostalgia is criticized because it signifies just how much of the “truthfulness” of the past can be sanitized and forgotten.

The act of forgetting is a mistake, an evasion of the past. In a world occupied by surrealism, fantasy and even absurdism, there are many who do not think twice about denying their past history but then there are those who are not only aware of their past but would welcome the chance to change it, especially when it is disappointing or even ugly.

Thirty years ago, the film critic Richard Corliss explained how the yearning for the past easily becomes a powerful temptation. He wrote that “just about everybody wants to wake up from the dreary dreams and claustrophobic nightmares of their own lives— that the present is edged with tension and boredom and, seen through the soft focus of nostalgia, the past is as sweet as first love.”

However, it’s not remembering or recovering the past that is really all that important. There is greater interest and significance in seeing and understanding how individuals – especially those who have known each other for the better part of their lives — continuously renegotiate their own cognitive and perceptive paths as they deconstruct, reconstitute and then deconstruct and reengineer again their cultural memories. What happens when our lives are disrupted, usurped and transformed by unexpected or anticipated death, incapacitation, paralysis, betrayal of belief, relocation from one end of the world to another, unforced or deliberate transgressions, spiritual epiphanies or, quite ironically, the stability of long-lasting friendships and relationships?

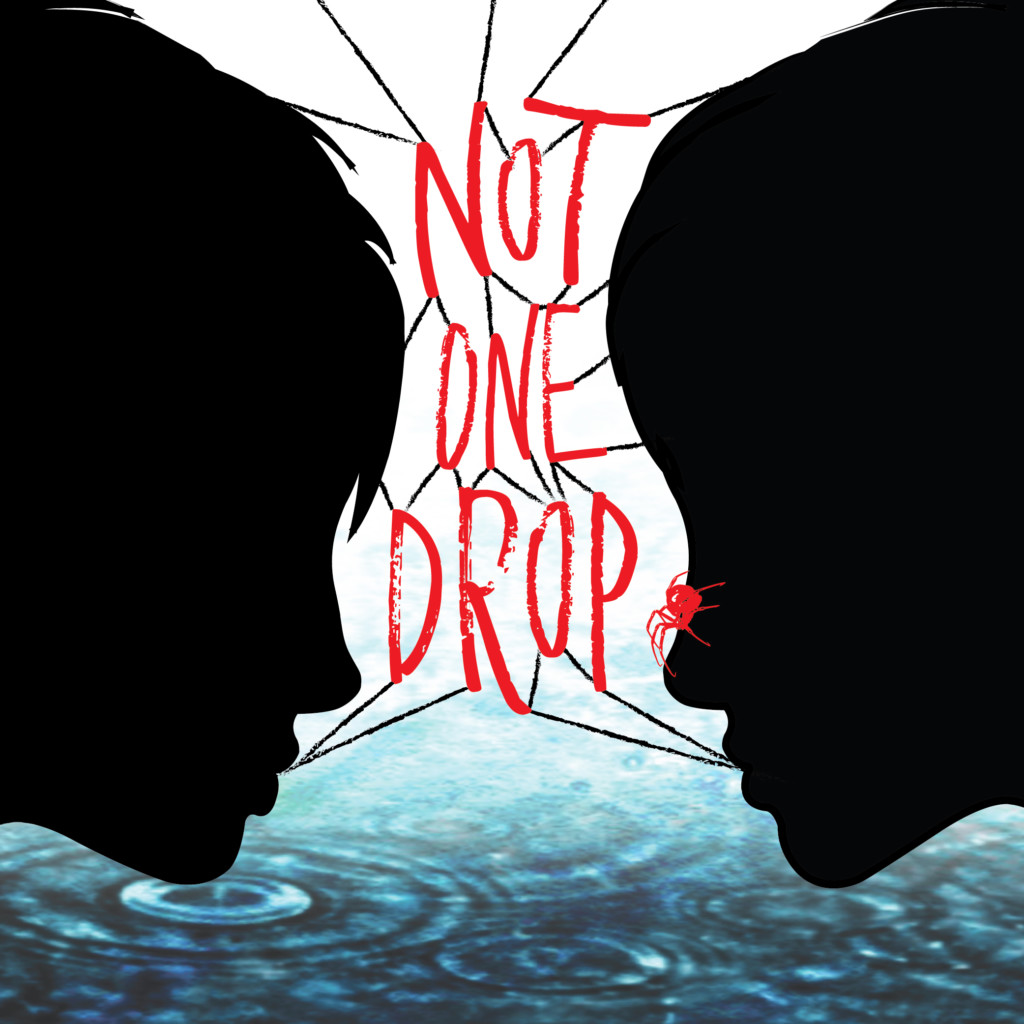

Near the middle of Morag Shepherd’s new play, Not One Drop, which will close out Plan-B Theatre’s 26th season, Rowe tells Aidan, “I want to hear your death. Your grave. … Do it like how I did it.” Aidan says, “I don’t like gravesites,” and Rowe says immediately, “Don’t be ridiculous.” In the next breath, Aidan says,

I went to the cemetery where all my grandmother’s people were buried. It was cold, and dark – even in the middle of the day.

The church was barely standing. Decrepit. Dreary. All but completely decayed. And around it, the stones, with half eroded words, cracked and broken, like an earthquake had ravaged the place.

No, I don’t like graves. It smells of grey and it smells of loss and cold.

I got the impression that they had been tricked into going in, and now were trapped there.

Which is why everything was splintered open.

Graves are just the living, playing dead.

Not One Drop’s world premiere run (March 23-April 2) highlights an aspect of Plan-B’s artistic brand that does not always garner the same attention as the company’s forte for socially conscious theatrical storytelling. Shepherd’s work is unique in how it supersedes formalistic structures as it focuses on two women who bring virtually every possible element of relationship drama and tension into the picture.

In fact, as Shepherd notes in a Plan-B blog post, “The nature of the relationship of the characters is constantly shifting and slipping – are they sisters, friends, lovers, enemies?– and ultimately it doesn’t matter. What matters is that they are so close that they slip into each other’s identities.”

Not One Drop is the third in the series of works by Utah playwrights 35 and younger, who were tapped as commission winners by the David Ross Fetzer Foundation for Emerging Artists (The Davey Foundation). As Jerry Rapier, director, explains, “Our mission is to develop and produce unique and socially conscious theater. Socially conscious gets a lot of play – but this piece fits squarely under unique, much like Eric Samuelsen’s The Kreutzer Sonata last season.” It is worth noting that Shepherd is the third Plan-B playwright who studied under Samuelsen during his tenure at Brigham Young University (the other two being Melissa Leilani Larson and Matthew Greene).

Shepherd’s play is being staged in the round – a first for the company– in the Studio Theatre at the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. The setting emphasizes the unique nature of Not One Drop for how it lays out the theatrical space that compels the audience to question and probe their own parallel experiences to the relationship Aidan and Rowe are acting out on stage.

The play promises a fascinating coda to an immensely satisfying season of theatrical enterprise, in which Plan-B already has seen sold-out runs for plays about Joe Hill, an early 20th century labor activist whose life ended when he was executed in Utah, and St. Hildegard of Bingen, a Benedictine abbess from nearly nine centuries ago whose exceptional achievements presage the ideal of the Renaissance individual. Likewise, the company garnered plenty of praise for The Edible Complex, a children’s play about body image and the reaffirming values of smart communication, and Yuletide, the latest Radio Hour series entry about the cultural impact of stories that have become part of the holiday season tradition.

In a season influenced heavily by history and by the complex dualities of identities in stories that often are more enigmatic and mysterious than they are conclusive, Not One Drop offers up profound questions of meaning and historical memory that target the process by which individuals pursue their own search for an inner “truth” with their experiences of a major event in their life. The value and significance of that historical memory is not in how the actual details and circumstances unfold, but as Shepherd explores with Aidan and Rowe, the takeaway lies somewhere in that space of consciousness between the actual experience and the process of remembering.

In an interview with The Utah Review, Shepherd says the play reflects “how close you become with people in your life” and “how we consciously question the experience and who does that experience belong to.” Memory is far from being consistently reliable as individuals pick and choose their memories, using fragments and shards to shape their broader perceptions and recollections – consciously, subconsciously and unconsciously.

Not One Drop’s form echoes this understanding of memory. Shepherd’s work conveys a particular visceral tone variously in the heavier dramatic and lighter even-comedic moments. The imagery of burn sensation was prominent in Burn, a work that was staged last fall by Sackerson, a Salt Lake City theater company that has explored experimental theater in content, form and staging. Burn’s theatrical contours, for example, are shaped in part by the playwright’s struggles with her Mormon faith and the realization that she does not have to try to fit into a religion she didn’t fit into, as she discovered.

However, the contours for characters in Not One Drop are completely liberated. “There is the freedom to let the voice be angry if it needs to be and not apologize for it,” she explains. The sometimes bleak, even fatalistic, elements of Not One Drop, articulated in the persistent imagery of drops of liquid substance and the motion of falling, serve a hopeful, emancipating purpose for the individual to regain her awareness of the events, issues, circumstances and experiences, as part of choosing between false consciousness and authentic self-discovery. It’s rebelling against the fictions that have masqueraded as our alleged identities.

The cast includes Colleen Baum and Latoya Cameron. Rapier notes that audience members will note the minimalistic set, designed by Dan Evans in his first production with Plan-B, which resembles a playground, an apt metaphor for how people continuously weave their stories through spaces of fantasy, reality and surrealism.

Performances are slated to run from March 23 to April 2 on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays at 8 p.m., Saturdays at 4 p.m., and Sundays at 2 p.m. For ticket information see here.

1 thought on “Plan-B Theatre sets to explore the culture of memory in Morag Shepherd’s Not One Drop”