NOVA Chamber Music Series’ 40th anniversary is filled with every distinctive element that has made its programming brand unique in the Intermountain West region. There will be numerous soloists from Utah’s deep bench of outstanding musicians, six commissions of new music and performances of music that should be heard more frequently than is the usual case.

The upcoming Gallery Series concert, the first of NOVA’s benchmark season, highlights one of the most significant aspects of the group’s programming brand – its unconventional, yet incisive, skill to match the musical blood relationships between old and new composers. The Fry Street Quartet will continue its four-concert cycle series of the complete set of six string quartets composed by Bela Bartók (1881-1945) and the six string quartets comprising Opus 76 by Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1809).

The works featured for this third concert of the cycle will feature three outstanding examples of string quartet literature: Haydn’s Opus 76, No. 2 Quartet in D minor, nicknamed Quinten for the opening display of descending fifths; Opus 76, No. 4 in B-flat Major, nicknamed Sunrise for the first violin melody heard in the opening 21 bars of the first movement, and Bartók’s String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, completed in 1909 and one of the key early works of the Hungarian’s mature phase as a composer.

The works featured for this third concert of the cycle will feature three outstanding examples of string quartet literature: Haydn’s Opus 76, No. 2 Quartet in D minor, nicknamed Quinten for the opening display of descending fifths; Opus 76, No. 4 in B-flat Major, nicknamed Sunrise for the first violin melody heard in the opening 21 bars of the first movement, and Bartók’s String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, completed in 1909 and one of the key early works of the Hungarian’s mature phase as a composer.

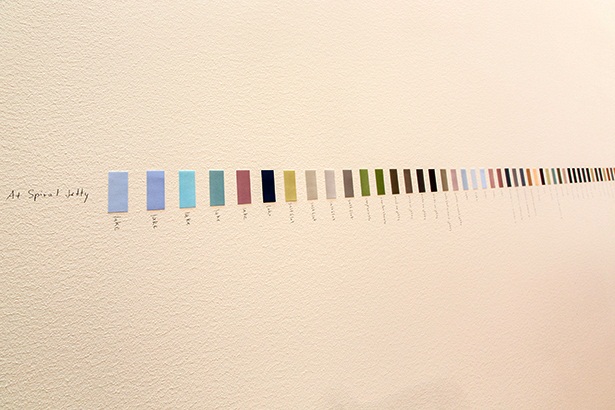

The concert will be performed Oct. 8 at 3 p.m. at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA), once the regular home of NOVA’s programs, in the G. W. Anderson Family Great Hall, which currently houses Spencer Finch’s Pantone chip installation Great Salt Lake and Vicinity, a commissioned work by the UMFA.

Traditionally, many music presenters have matched Haydn to two of the most formidable contemporaries of his day, Mozart and Beethoven, but it is more enlightening to listen to how Haydn, born an Austrian but who worked for many years under the employ of Hungarian patronage, and Bartók, the native Hungarian, inculcated the Magyar roots of folk music into their works. Musically, Haydn and Bartók are more precise blood relatives than what others conventionally assert.

In the old Austria-Hungarian Empire, Haydn served for many years as the court musician and composer for Prince Paul Esterházy. It was the standard employment contract for composers of his day, which Haydn agreed to in 1761. He was required to be at hand in the morning and afternoon at the prince’s chambers if the royal court desired a concert for that day. More importantly, the rights for the works he composed belonged to the prince.

Only in the 1780s, as the light of the Age of Enlightenment grew, the restrictions were loosened and Haydn’s works began to circulate more freely around Europe. In 1796, when Haydn was 64 and his reputation growing in respect and visibility, Beethoven had dedicated a set of three piano sonatas to Haydn. Meanwhile, Haydn began writing the Opus 76 string quartets, which were commissioned by Joseph Erdödy, a Hungarian count. He completed the set in 1797 and the quartets were published in 1799 by the Vienna music publishing house of Artaria, which proclaimed (as translated from German), “Nothing has yet been presented by us that could equal this publication.”

More than 110 years later, Bartók, at 27, was still in the midst of his massive project of documenting his homeland’s folk music traditions, which bridged Western and Eastern civilizational roots in unique ways and instrumentation. The young composer had expanded his work, going to Transylvania, Romania and Bulgaria as well as the Berbers in North Africa. His first string quartet clearly displays the characteristic kineticism, his deep love of polyphony and the new harmonic language of Modernism.

Haydn may have been in his middle sixties when he began working on the Opus 76 quartets but these late works – he would only write five more string quartets after this collection – are exuberant and youthful. Forty years earlier, he had ventured into “blue ocean” territory with the string quartet form. These works are as complex as they are delightful — with Haydn, the music always suggests eternal youthful spirit.

Haydn never tired of experimenting with the standard form of the four movements in string quartets. The Quinten work underscores this: the opening movement with a short main motif acting as the basis for a counterpoint sonata form, marked as allegro in tempo; the second movement structured in the usual ternary form where the first melodic section is repeated after the second one, the minuet and trio form of the third movement but also incorporating a canon and longer pedal point, and the last movement, a unique mix of rondo and sonata forms, and its tempo is marked as vivace assai, the quickest of the work.

The result in Quinten is a bracing composition with plenty of syncopated rhythms, especially as Haydn toys with the motif and its inverted expression. The second movement is so characteristically elegant but while the overall sound of it is clean and pure, it challenges devilishly the musicianship of the quartet. The third movement also is known as the ‘witches minuet,’ with the violins playing an eerie musical idea in octaves, which is then imitated by the viola and cello. This sets up the two-canon element of the movement, one of Haydn’s famous twists. The closing movement is the most Hungarian sounding of the work, the whirling rhythms and the signature Magyar augmented intervals percolating among all four instrumental voices.

The Sunrise Quartet definitively ranks among the top tier of the composer’s 68 string quartets. In the opening movement, marked allegro con spirito (a tempo which actually begins in the 22nd measure), the three lower instrumental voices produce a cloud bank of sustained harmonies while the first violin sings poignantly, a spiritually satisfying evocation of daybreak. But, while many might be entranced by the first violin’s melodic prominence, listeners should key in on the viola, which has among the most difficult parts the composer wrote in any of his string quartets.

This work especially stands out because it is cast in B flat major, a key the composer used infrequently in his string quartet output. The opening movement expands in complexity, both melodically and rhythmically, and Haydn enjoys playing with both the original theme by the first violin and the second, which is played by the cello in the dominant key of F major. Throughout the movement, the listener is rapt by the blissful organic unfolding of a work that has begun so simply without ever having to worry about where the composer wants to end it but the listener can hear clearly the character of the movement’s themes.

There is a noteworthy irony. Mozart, who had died five years earlier, incorporated so much of Haydn’s compositional experiences into his own string quartet writing. In this opening movement, it is evident why Haydn’s works always sound so youthful, hopeful and playful.

The second movement, marked adagio, is a radiant expression of spiritual depth that presages Beethoven’s greatest chamber music, while the third movement, a menuetto, leaps with rhythmic agility. The closing movement accelerates in tempo, echoing the composer’s appreciation not only for exuberance but good-natured teasing and mischief.

The explosion of youthful elements in both Haydn works find a solid 20th century connection in Bartók’s first string quartet. It is well known that the composer set the opening four notes as a motif evoking the Magyar melancholy that overshadowed his life. His unrequited love for a violinist (Stefi Geyer) inspired the work, which is in three movements and runs approximately 27 minutes. The work is played without any pauses between the movement and listeners will discern the organic character of tempo throughout the piece, moving from the slow pace of the first movement, often described as funereal, through the faster yet still moderate tempo of the second, and then the blazing acceleration in the final movement.

While many music historians and theory scholars have spent great deal of time and energy to dissect and distill Bartók’s compositional techniques, it is more appealing and more consequential to why many of today’s audiences relate to the physical and visceral imagery in his music. More than seven decades after his death, Bartók’s musical voice inspires budding composers of all stripes and styles, filmmakers, videogame creators and adventurous audiences.

The First String Quartet is a good example. Many writers have tried to explain how the work echoes the Romantic Era impulses of Beethoven or Wagner, but Bartók captures complexities in dense harmonic structures and notes (a wickedly difficult score for chamber ensembles). And like his earlier blood brother of music, he builds on characteristic pentatonic inflections and the continuously flexing rhythms of folk music in the last movement, but, alas, even then, Bartók still cannot let go of the haunting motif of romantic disappointment that opens the work.

All three works are intimate musical dramas which will resonate in the art gallery location of the performance, which includes a short discussion prior to the performance of each work by Robert Waters, Fry Street Quartet’s first violinist.

The Fry Street Quartet has been an integral part of NOVA’s programming, an internationally acclaimed ensemble that has been in residence at Utah State University’s Caine College of the Arts for more than a dozen year. Recent recipients of the national Fischoff Competition Grand Prize, the ensemble is in constant demand across the country and around the world – from collaborating with the Lyric Opera of Kansas City on producing Elvis Costello’s The Juliet Letters to The Crossroads Project, a multi-media performance focusing on climate change. “The quartet’s presence in Utah is a rare prize that has energized the local music scene in countless ways,” Hardink says.

For more information, tickets and series subscriptions, please visit NOVA’s website.