A truly contemporary landscape representation animates the upcoming NOVA Chamber Music Series concert Songs of the Americas (April 10, 3 p.m., Libby Gardner Hall at The University of Utah). The concert, which celebrates not just the U.S. but the whole diasporas of the entire American continental geography, will feature works by three composers already represented in earlier concerts of the seasons: Gabriela Lena Frank, Jessie Montgomery and Clarice Assad.

These include Four Folk Songs by Frank; Loisaida, My Love by Montgomery, for cello and mezzo-soprano, which celebrates the history of Puerto Rican activism in New York City’s Lower East Side, and Canções da America by Assad, a string quartet commissioned for a Utah State University debut that occurred last October with the Fry Street Quartet. Anthony R. Green’s Gettysburg Address is a 2010 work that nine years later was featured in an artistic residency the composer received as sponsored by the National Parks Arts Foundation. This concert theme would not be complete without highlighting selected songs from Charles Ives, an American composer who has yet to receive his full due merit as one of the country’s most important musical figures.

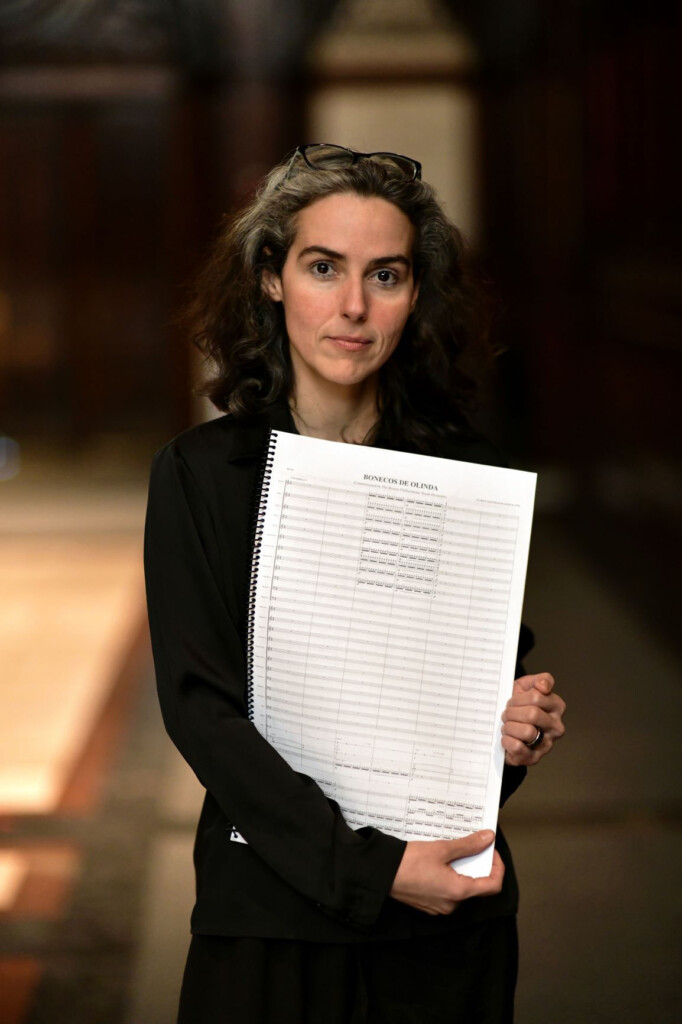

Assad’s work will be given its second performance in Utah. Last October, the Fry Street Quartet, who also serves as NOVA’s music director, gave the world premiere of Assad’s Canções da America in a Utah State University concert, where the quartet is in residence at the music school. While so much of Assad’s original music springs from her Brazilian roots, this work explores influences from her native country’s neighbors including Argentina, the home of Claudia Montero, a composer whom Assad considers a seminal mentor to her and peers in recent generations of South American women composers. The six movements, as Assad, tracks in her note for the work, emerge from various dance forms including Uruguay’s Milonga Brazil’s choro, and Argentina’s tango as well as music of Paraguay and Andean melodies associated with Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador and Indigenous peoples.

This is the second piece the Fry Street Quartet has commissioned from Assad. The first was Pandemonium, a concertino for string quartet and string orchestra, which was premiered by the San Jose Chamber Orchestra in 2012. Assad says that among her most valuable experiences for developing as a composer came from doing arrangements by a deep dive into original scores, which she did for the New Century Chamber Orchestra.

“The quartet [Canções da America] is peppered with dances, themes and gestures that celebrate life,” Assad said in an interview conducted last fall with The Utah Review. While she selected traditional dance forms with familiar harmonies, she also teased out some of the more unpredictable roots in those forms. Thus, she capitalizes upon modulating the harmonies through keys that might not resolve at the moment or end up resolving in a surprising way later in the work. Likewise, she plays with rhythmic contrasts that swing from perpetual motion to nearly static. The idea is to keep the listener’s brain on alert. As for writing for the Fry Street Quartet, Assad said, “they have no limits and enjoy the freedom of experimentation. The clashes in harmonies along with the dissonances, they play them with pure joy.”

This is the second opportunity within the last three weeks for Salt Lake audiences to hear a work by Green, an internationally known composer. Last month, Green’s Baldwin Sonata received its world premiere by pianist Jason Hardink at the three-concert event Concord/Revisited at Westminster College, which celebrated the centenary of Charles Ives’ Concord Sonata. As The Utah Review noted recently, in elucidating the literary legacy and profound influence of James Baldwin. Green found the parallel that inspired Ives to create the Concord Sonata in the first place. Ives had taken the unique opportunity to write about local authors, who were alive when he was growing up in the mid-19th century. Baldwin, who died when Green was still very young, is a monumental influence for the composer. Thus, the sonata comprises quotations and other elements that have been instrumental in Green’s life, much in the same way that Ives incorporated those of his own life in the Concord Sonata.

While the Baldwin Sonata highlighted a great deal of spaciousness in its score, Green’s earlier work, Gettysburg Address, written when he was 26, is fuller, denser and more compact. “I was much more attracted at the time to pleasing a certain type of new music connoisseur,” Green says in an interview with The Utah Review. In his formative years, he was alerted to various composers including Karlheinz Stockhausen, Elliott Carter, Jason Eckardt (who also had a world premiere work at Concord/Revisited), Edward Bland, Helmut Lachenmann and others.

The work originally was composed as a commission by The Playground Ensemble, which premiered it in Boulder and Denver during the spring of 2010. Gettysburg Address also was featured on the ensemble’s debut album Dreams Go Through Me.

Many know the historical account of the occasion and delivery of unquestionably the most famous speech ever given by a U.S. president. In fact, the 1863 event highlighted Edward Everett, one of the country’s most famous orators of the time, as the main speaker. Lincoln was scheduled to deliver a few remarks as protocol. There are five versions of the speech. Green uses a version that was among the earliest ones available. In Lincoln’s own handwriting, he omitted the mention of God in the conclusion. Thus, it read: “The nation, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people by the people for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” Apparently, at the dedication, Lincoln added the reference to God.

Green says that he had wanted to compose something different from the usual patriotic hagiography associated with the speech, which took barely two minutes to deliver. The 12-minute work is scored for soprano, clarinet, cello, piano and percussion. Red Desert ensemble co-founder Devin Maxwell will conduct the NOVA performance, which is a Utah premiere.

When he wrote the piece, he had never visited the Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania. In 2010, when the work premiered, he said the initial response was somewhat mixed, as some audience members did not applaud at its conclusion. “The honesty and vulnerability of the work were too much for some people,” he recalls. But, it also turned out to be a project of prescience. Nine years later, its reception was different, reflecting those subtle yet significant shifts in conscious reflection and awareness of how the vision Lincoln articulated in that speech has yet to materialize or crystallize in its sincerest possible form. Green says that in 2019, when he was in residency for the performance at Gettysburg, he burst into tears and started singing the work in its entirety, inspired by interacting with the physical presence of the location of the Civil War’s bloodiest battle. And, it is in Green’s music, that the most critical takeaway of Lincoln’s speech, delivered in wartime but with a vision that extended far beyond 1865, reminds us of “the great task remaining before us.”

For tickets and more information, see the NOVA Chamber Music Series website.