It is inexplicable how some of the most gifted, passionate and prescient pioneers of form, expression, and ideals in the arts and letters world languish in obscurity before someone rediscovers and revives their work, which often is more relevant now than during the period in which it was created.

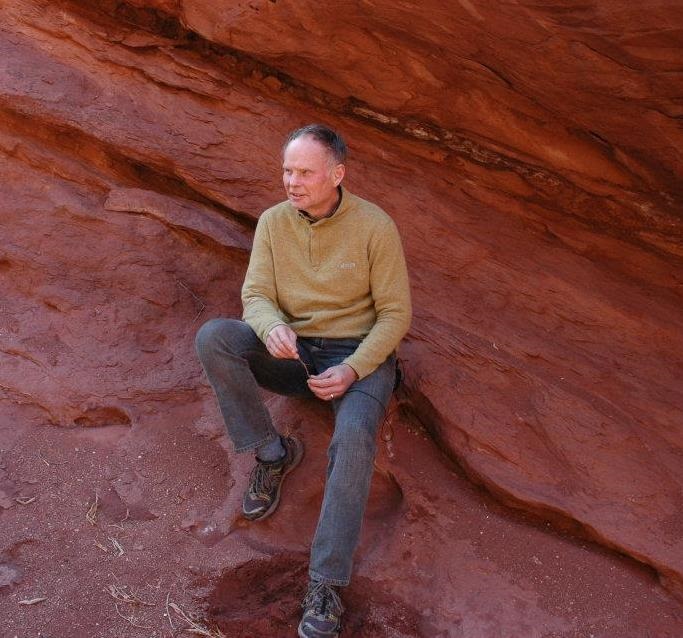

The words of a nearly forgotten book set down in print more than 130 years ago had seized the imagination of Brooke Williams, who found a copy of ‘The Story of My Heart’ by Richard Jefferies. Brooke and his wife, Terry Tempest Williams, one of the most influential contemporary authors of books in environmental humanities, were vacationing in Maine when he noticed this little book. While both were surprised and deeply moved to rediscover Jefferies’ work, it was Brooke, an author of four books and a high-profile figure for more than 30 years in various organizations of the conservation movement, who not only has revived but also has reevaluated the significance of this book which effectively encapsulates the 19th century British author’s legacy.

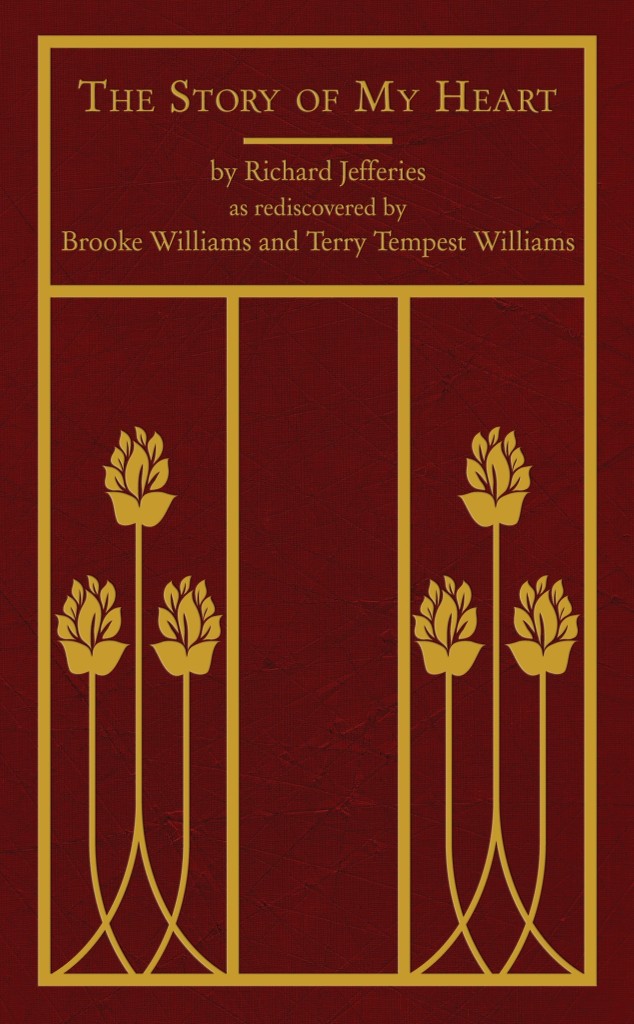

The result is an outstanding new book – ‘The Story of My Heart’ by Richard Jefferies as rediscovered by Brooke Williams and Terry Tempest Williams – published by Torrey House Press that offers a monumental, urgent lesson for today’s conservation and environmental movements. If these movements are to succeed in making the most critical case for saving the world’s natural landscape, activists and advocates cannot ignore or discard important philosophical questions that must always come first in a process of research and policy that legitimately integrates the most appropriate aspects of the value of science, the acceptance of scientific authority, and the well-being of society.

Brooke responds in each of the 12 chapters to Jefferies’ original text, laying out an exquisitely compact peroration for why this 19th century author hit with marvelous consistency on the right ideas of our times. Brooke, however, also explains how Jefferies distills these ideas in terminology that resonates today with clarity not perhaps as apparent in the author’s day. Not only should today’s environmental activists, thinkers, policymakers, and advocates deal with the grand environmental challenges such as global climate change, species protection and management, and emergent diseases, they also must contemplate and act upon the global ethical implications of working through these challenges. Indeed, as Jefferies reiterates frequently, expecting to continue on the current path in terms of economic development and sustaining our comfortable lifestyles would be incompatible, illogical, and unethical if we are to not only preserve and restore our natural landscapes but also to ensure there is respectful, dignified harmony among societies in the well-developed, developing, and under-developed countries of the world.

Brooke writes in an engaging antiphonal style responding to Jefferies’ text. He makes Jefferies less obscure and distant, as he shares illuminating facts and bits about the author’s life, of which still little is really known. Even as he is passionate about Jefferies, Brooke admits that sometimes the author can be repetitive and that certain ideas only become apparent after reading passages several times. Brooke also gives readers numerous glimpses into his own epiphany making experiences as well as those of Terry. Readers also are rediscovering the inspirations and motivations for two individuals who have become so prominent in the global environmental and conservation movements.

The new book is a first-rate tribute to an author who now has been rescued from obscurity. Community members in Swindon, the English community where Jefferies lived during his short life (he died at the age of 39), have recently ramped up efforts to make a museum honoring Jefferies a more visible destination for tourists and those curious to learn about this unusual, prescient ecologist.

Jefferies was familiar to his contemporaries. To some, as Brooke notes, he was an introvert, crank, and ineffectual writer. However, Jefferies managed a prodigious output that included many nonfiction works about his surroundings, numerous articles for national and local media, avant-garde fiction, and even children’s books, which were illustrated by E.H. Shepard, the British artist who drew characters for the Winnie the Pooh and The Wind in The Willow stories.

Broadening the perspective, Terry, in her introduction to the book, writes elegantly and precisely, “Richard Jefferies was a champion of rigorous inquiry, a lover of beauty, and an advocate for natural and social justice. He was an advocate for the poor, a friend of farmers’ rights in the rise of Britain’s urbanization. ‘Never, never rest contented,’ he said.”

Well before the time Jefferies had even reached his adolescent years, Transcendentalism was going full speed in the United States, as represented in the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller and Henry Blake. Emerson’s ‘Nature,’ published in 1836, had inspired many others including Thoreau’s ‘Walden’ (1854) and Walt Whitman, who was turning out poems encompassing transcendentalist beliefs, as in the collection titled, ‘Leaves of Grass,’ published in 1855 but revised continuously throughout the remainder of his life. However, Thoreau would already be gone by the time Jefferies was just starting the adult phase of his work in the 1860s.

Assuming Jefferies, indeed, had encountered the work of American Transcendentalism, one can identify quickly the parallels in the respective works, which comprise an apogee of sorts for secular humanism as a supra-religious domain. Brooke takes prominent notice, explaining how Jefferies, like Thoreau, was a mystic of nature, and how they viewed the activities of walking and wandering. In ‘The Concord Saunterer,’ journal of Thoreau studies, Reginald Lansing Cook (1985) describes Thoreau:

“He had noticed that when he thought his walk was profitless or a failure, it was then usually on the point of success, ‘for then,’ he surmised, ‘you are that subdued and knocking mood to which Nature never fails to open.’ One late August day, in 1851, when it appeared to him that he had walked all day in vain and the world, including field and wood as highway, had seemed trivial, then, with the dropping of sun and wind, he caught the reflex of the day, the dews purifying the day and making it transparent, the lakes and rivers acquiring “a glassy stillness, reflecting the skies.’ His attitude changed, and he took what Keats called “the journey homeward to habitual self.’ He exulted in the fact that he was at the top of his condition for perceiving beauty.”

Jefferies also championed wandering, avidly cherished by Brooke as well. “Wandering is goalless, open-minded,” Brooke writes. “In my own experience, wandering is directly related to imagination and creativity—and, I believe, my spiritual evolution. When my ideas run out or no longer serve me I will go wandering in the desert to gather more. Jefferies and I share this.”

Reading Jefferies and then thinking about the powerful imprint he has made upon Brooke, the reader likely wonders how Jefferies’ legacy could have fallen so precariously into obscurity, unlike Emerson, Thoreau or Whitman who have inspired enduring generations of readers who aspire to be as spiritually enlightened as the great Transcendentalists. Jefferies, on the other hand, appears so inward and even incomprehensibly introspective at times that one can understand perhaps why so few were touched to the point of carrying forward his literary legacy after his untimely death in 1887.

Witness to the rapidly expanding impact of the Industrial Age in his native land, Jefferies sought to contextualize the possibilities of a dangerously comprised future in broader terms than the ideas of soul, immortality and deity which he contended had undergirded the development of civilization’s intellectual history. He believed, as Brooke explains, that humans would need a fourth idea if they were to meet the dire challenges that today have become the source of today’s extremely agitated, not always productive debate.

Likewise, Jefferies was a critic of Charles Darwin, preferring instead Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s ideas about evolution, which had been displaced at the time. However, as Brooke notes, Lamarckian ideas have recently been rehabilitated by scientists working in the field of epigenetics which suggests that other factors may be involved in cellular and physiological changes than just DNA sequences.

Brooke offers a useful perspective in explaining perhaps just what Jefferies was dealing with during his time. “I realized that lurking behind my eyes, back there in the shadows, is the feeling of how frustrated Jefferies must have been. I feel it in his prose, between the lines and in the margins. I don’t think he was at peace in the sense that Whitman was. In ‘The Story of My Heart’ he longs for something—he’s not sure what.”

Brooke also brings it forward to our formidable issues of today, such as climate change. “Our main problem may be thinking that all major discoveries have been made and solving problems is a simple matter of bringing different elements of our knowledge together in the right combination,” he writes. “With climate change, this may spell disaster, as experts believe that successfully dealing with it will require all that we now know and a lot we don’t yet know.”

Jefferies’ obsession also is Brooke’s obsession, Terry explains, something evident long before both of them discovered the book. “Being married to a man whose physical life is intrinsically tied to his spiritual life, I understand Jefferies’ obsession with the ‘exaltation of the body, mind and soul.’ I have watched Brooke and my obsessions of the body change over time,” she writes. She adds, “My own physical relationship to the land has largely been following Brooke. He was so strong, so focused, so driven, that I often lagged behind – I was distracted by birds, by plants, by tracks. But an unexpected gift emerged. I had the illusion I was walking in the words or the desert or the beach alone. My life has been a protected solitude.”

Jefferies’ prose upends conventional perceptions at many turns. He writes, “The supernatural miscalled, the natural in truth, is the real. To me everything is supernatural. How strange that condition of mind, which cannot accept anything but the earth, the sea, the tangible universe? Without the misnamed supernatural these to me seem incomplete, unfinished. Without soul all these are dead.” He does not see miracles as astonishing: “I can see nothing astonishing in what are called miracles. Evidence is logically and historically untrustworthy. Miracles would be perfectly natural. The wonder rather is that they do not happen frequently.”

Jefferies’ prose takes effort to digest but Brooke’s companion ‘meditations’ highlight and guide effectively toward discovering some marvelous phrases of imagery. In the hugely important chapter dealing with cosmic consciousness and the historical experience of two thousand years, Jefferies writes, “The azure morning had spread its arms over the low tomb; and full glowing noon burned on it; the purple of sunset rosied the sward. Stars, ruddy in the vapour of the southern horizon, beamed at midnight through the mystic summer night… Mystery gleaming in the stars, pouring down in the sunshine, speaking in the night, the wonder of the sun and of far [space.]”

Brooke’s response is equal to Jefferies’ sense of marvel:

“This feels familiar. I’m constantly searching for meaning and truth, while for Terry, meaning and truth are part of the air she breathes. Mimi [Terry’s grandmother] believed in reincarnation and often talked about people in terms of how many times they’d “been around” – are they open and receptive to new ideas, nurturing, and comfortable with mystery? Or, is this their first time around – are that difficult, narcissistic, moody? Mimi said that Terry has “been around” many times. I know she’s been around more than I have, but that this isn’t my first time. There’s real magic at play here.”

Indeed, part of the magic is rediscovering a once-obscure book which provides important philosophical lessons about how we should go about the extraordinary work needed to rescue, sustain, and rehabilitate our fragile ecosystems and natural landscapes.