From several notable vantages, there has been a great infusion of artistic energy in the blossoming Utah Enlightenment, a creative movement that demands courage in the making of art. And, especially in Utah’s peculiar environment that gives civility, docility and adherence to faith much higher value than often deserved, courage becomes critical in ensuring the secular realm is nurtured by a greater sense of purpose than for the sake of showmanship and entertainment.

Sometimes, the making of art goes to a much-needed space of being discomforting for an essential, valid purpose. “The public is in need of experiences that are not just voyeuristic,” artist Marina Abramović said in an interview for Sarah Thornton’s 2014 book ’33 Artists in 3 Acts.’ “Our society is in a mess of losing its spiritual center… Artists should be the oxygen of society. The function of the artist in a disturbed society is to give awareness of the universe, to ask the right questions, to open consciousness and elevate the mind.”

Sometimes, the making of art goes to a much-needed space of being discomforting for an essential, valid purpose. “The public is in need of experiences that are not just voyeuristic,” artist Marina Abramović said in an interview for Sarah Thornton’s 2014 book ’33 Artists in 3 Acts.’ “Our society is in a mess of losing its spiritual center… Artists should be the oxygen of society. The function of the artist in a disturbed society is to give awareness of the universe, to ask the right questions, to open consciousness and elevate the mind.”

The current Plan-B Theatre production of Matthew Ivan Bennett’s newest play ‘A/Version of Events’ is an outstanding addition to the growing canon of Utah Enlightenment works. It achieves precisely what Abramović explains as vital to the experience of substantive artistic expression.

Indeed, it is disconcerting that some people see Bennett’s latest work – and, unquestionably, the best of the 12 plays he has had produced on the Plan-B stage – as being too uncomfortable to watch. Plan-B’s productions have enjoyed a remarkably consistent high percentage of sold-out houses but not so here at the moment. Jerry Rapier, the company’s producing director, says of ‘A/Version of Events, “the subject matter scares people. We’ve heard that quite a bit.”

In handling the wider topic of bereavement and the utter shock of a how child’s accidental death can render the marital relationship as strange and unfamiliar, Bennett’s play is brilliant. It establishes a strong sense of place while simultaneously demonstrating the tremendous difficulties of articulating grief and of the prevailing senses of unreality and dislocation with which Cooper and Hannah must contend.

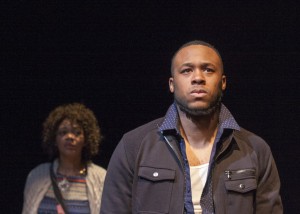

And, it is the searing, riveting and magnificent performances of Carleton Bluford and Latoya Rhodes which show just how a couple’s struggle to cope with a child’s death is so chilling and stunning in its reality. So convincing is the performance that one could believe Bluford and Rhodes are the actual married couple, down to body language and facial expressions. It is a most powerful depiction in every sense – a new hallmark in Plan-B Theatre’s distinguished record of bringing courageous new works to the stage.

Cooper and Hannah have different agendas, both struggling with the profound foreign effects of the route they are traveling on westward from New York City into Pennsylvania. Cooper believes solace is to be found in strengthened kinship with Mormonism. Hannah sees the shortcomings of emptiness, even betrayal, in a religious faith that cannot offer sustainable explanations for events.

During a traffic stop by a cop who has pulled their car over, Cooper tells Hannah that he is disturbed by the changes he is seeing:

‘Cause frankly I don’t know what this is. I can’t even be angry at you, I’m, I’m stupefied. I mean, are you trying to be the Bad Girl? From a movie? The Beautiful Dangerous Girl who’s so “free” she can’t be controlled or resisted?’

Hannah responds, “That’s your movie, but it’s not me. I’m just trying to get some place that hurts a little less. And if I drop a few F-bombs in the process and that scares you that’s about you, not me.”

Pained deeply by her response, Cooper just barely avoids breaking down while Hannah resolutely proclaims, “A woman isn’t a statue, she’s animate, she moves, she’s different now in this moment versus that moment. She’s a series of events. Not a list of qualities.” As with the lost earring, Hannah insists on moving forward: “But we’re brand new in every moment, both of us—we could be anything, Coop.”

Tensions, however, continue to mount, prying open the question of whether the wedge between Cooper and Hannah could ever be removed. This occurs especially as the circumstances surrounding their child’s death become more dominant in their exchanges late in the play. Cooper sees the trip as an opportunity to discover the “truth.”

Hannah reminds Cooper that the trip was his idea: “You bring it up at your family’s when my mouth is full of mashed potatoes and your mother says, “Oh, that’s a splendid idea” and you two glance at each other.” Cooper asks her, “What do you think we’re plotting?”

Hannah is exasperated by Cooper’s insistent ‘agenda’: “You’ve had this look like you’re on a deadline at work, your feet to the fire, but you have nothing to do but eat, drive and enjoy yourself, so what do you want, Cooper? What “truth”? I don’t know how to be any more upfront!”

The question becomes whether these raging waves of meanness and contempt will inevitably overwhelm those of kindness and love both apparently still carry for each other. Bluford and Rhodes are exceptional in this difficult scene. They demonstrate so effectively how hard it is for kindness to be displayed during a fight even as they are acutely aware of why this would be the most crucial time to be kind.

Bluford and Rhodes shine as exquisitely disciplined actors, reminding us of the dangers of letting our emotional aggression and contempt spiral to a point of no-return where the relationship damage could never be repaired.

Adding deeper resonance to the production, set nearly entirely in an automobile, is Christy Summerhays’ direction and Cheryl Ann Cluff’s music and sound design, helped significantly by Bennett’s own script suggestions for Hannah’s ‘road mix.’ The music includes ‘The Power of Love’ by Huey Lewis and The News, ‘Faith’ by George Michael and ‘Take My Breath Away’ by Berlin, just to name a few. Cooper and Hannah act out through these musical interludes, enriching yet further Bennett’s comprehensively detailed character portrayals.

In Bennett’s play, brought so memorably to life by the searing performances of Bluford and Rhodes, we learn it’s okay to accept grief’s messy, complex process that does not have to become an exercise of navigating neatly defined stages. By the play’s end, we recognize it is grief’s messiness which makes us most uncomfortable, almost to the point of being blinded, for example, to the still important ‘come weal, come woe’ proposition of marriage.

Five performances remain and tickets are available for all shows in the run which ends March 15. Ticket information is here.

1 thought on “Magnificent, searing performances carry Plan-B Theatre’s outstanding premiere of ‘A/Version of Events’”