The closing scene of Bamboozled, Spike Lee’s 2000 provocative film, is a montage of historical images that critic Ashley Clark says encompasses “blacked-up Hollywood stars like Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney; black stars in demeaning ‘coon’ and ‘mammy’ roles; racist cartoons; and disturbing scenes from films like The Birth of a Nation and Gone with the Wind.”

The scene puts the devastating point on Lee’s satire. Bamboozled’s story is about a disenchanted black television producer who creates a blackface variety show set in a watermelon patch on an Alabama plantation so he can get himself fired and expose his employer for its true racist bearings. That TV show becomes an embarrassingly popular hit, which triggers the producer’s mental collapse and violent acts.

At the time of Bamboozled’s release, many critics were disturbed. They thought Lee dangerously let polemics overtake his satire and that the “scabrously risky comedy” (as one New York Times critic described it) descended into unproductive melodrama. However, the closing montage validates and reinforces appropriately the film’s thematic intent, according to critic and film curator Ashley Clark, whose book Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee’s Bamboozled was published last year (The Critical Press).

Contravening those critics who panned the film as an odd, ineffective project for a talented director, Clark summarizes Bamboozled as “a vital work that’s equal parts crystal ball and cannonball: glittering and prophetic, heavy and dangerous.” He added that the film “flopped when it was released, I suspect in large part because of its insistence at looking so unsparingly at the continuum between America’s racist past and present.” Given where we are politically and socially in this country today, we need to face with full understanding, as Clark suggests, the “peculiarly insistent ‘neo-blackface’ phenomenon” (to wit: think of the recent Rachel Dolezal controversy and justifiable outrage).

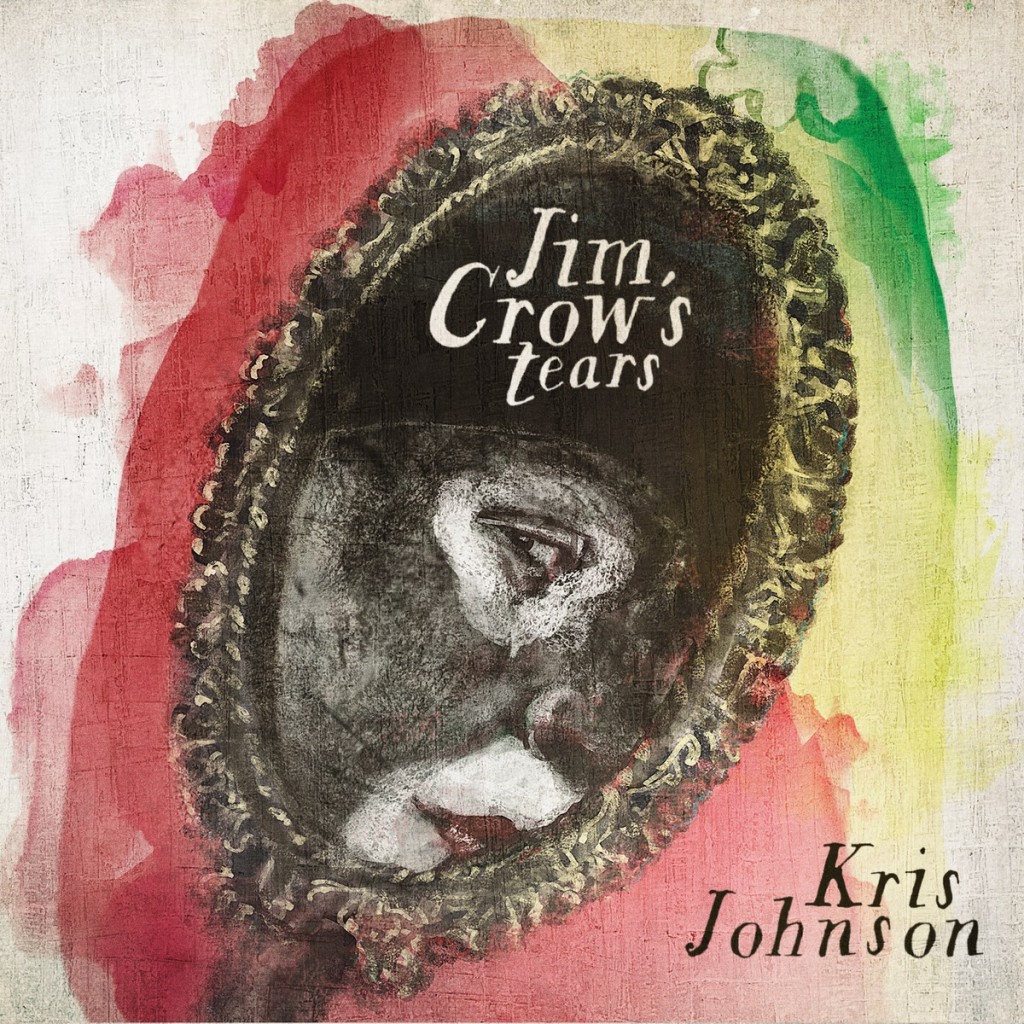

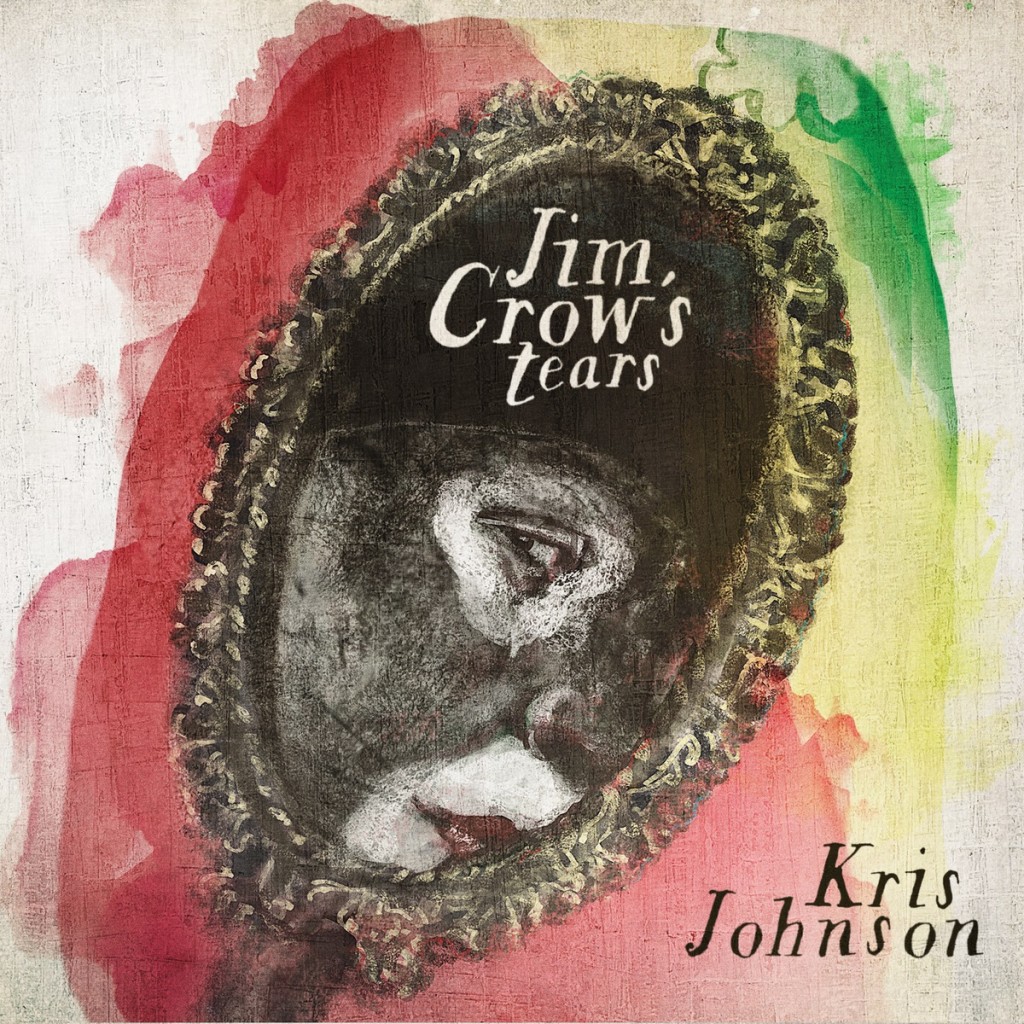

In Jim Crow’s Tears, a new album that really is a jazz musical, Kris Johnson has written and arranged music and lyrics that build upon Bamboozled’s uncompromising look at the tenacity of the worst stereotypes in our history. Audacious in every respect, Johnson’s album offers up a musical gift that is persuasive in its many socially incisive epiphanies.

Jim Crow’s Tears emerges as a masterful exemplar championing jazz not as a racial but as a cultural phenomenon. Johnson is astonishing in his depth and ease at writing jazz music that echoes virtually every point of its historical development. Just as he is inspired by Lee’s Bamboozled, Johnson also is compelled to find the light above the gray haze and forbidding clouds of today’s difficult, profound disturbances of race and culture.

The songs and music convey rightfully deep anger but they also reflect the touching and pragmatic faith that Ralph Ellison alluded to in Invisible Man, one of the 20th century’s greatest novels (Random House, 1952), where he writes, “The conscience of a race is the gift of its individuals who see, evaluate, record…We create the race by creating ourselves and then to our great astonishment we will have created something far more important: We will have created a culture. Why waste time creating a conscience for something that doesn’t exist? For, you see, blood and skin do not think!”

The cast of six singers handle eight roles. The main character is Lucius Purifoy, who has tried to forget his past as he has found great success on the minstrel show circuit when he performs in his character of Jim Crow. He is confronted by a memory that unsettles how he can continue living status quo in a racialized world. In the opening song, each member of the ensemble introduces each character – Tambo, Bones, Mulatto, Jezebel and the evil Massa, all classic minstrel characters. They sing, “We’ve come to coon for you, Dear Massa. We’s hope you like how black we act, now sit back and enjoy we’ll coon for you.”

When Jim Crow makes his first appearance in the song Never Approve, Lucius/Jim Crow intones, “All my life I’ve been seeking some sign of my actions pleasing. Dear old Massa Purifoy, a cold and lonely, broken man. Despite my efforts to appease he never would approve.” The first act unfolds as flashbacks reveal the true story behind his mother (Pearl the Jezebel) and how he ended up as a popular minstrel performer. The second act leads to the penultimate declaration, “There will be no more coonin’ for us.” The song These Chains is a tour de force lyrically and musically, as Jim Crow and his fellow ensemble performers realize “there must be another way.”

The singers (Antwaun Stanley, Stacey Carter, Sarah Elizabeth Charles, Kenny Watson, Milton Suggs and Rusty Mewha) rise at every turn to the complex challenges of story-telling through jazz songs. Jazz vocalists often have many liberties including improvisation and rhythmic flexibility. The true test of many of the songs featured in Jim Crow’s Tears is that they could be lifted out and performed individually to convey the subtleties, humanity and dramatic purpose of the composer’s intentions, right down to where syllable and beat breaks occur.

Johnson’s musical score is thoroughly accessible for all listeners, whether they are jazz aficionados or newcomers. Every line and every note in the album’s 22 tracks open a path away from the harmful distinctions and distortions that have paralyzed us in our ability to see really the most painful aspects of our national and social existence today. Johnson wrote all of the material with the exception of Motherless Child (1918), the great spiritual song which was most famously arranged by Henry ‘Harry’ Thacker Burleigh (1866-1949), a classically trained opera baritone. The book is by playwright Gary Anderson. Johnson also mentions jazz trumpeter Terence Blanchard, who is credited with the music for Lee’s film, as an inspirational source for the album.

While Hillary Clinton definitely could have been more artful in her campaign comments about a “basket of deplorables,” Johnson offers excellent examples in his songs by adding the informative nuances to those overt manifestations of racism that show precisely how white patriarchy functioned to oppress Lucius. In the song, Massa Come Down, while the ensemble interjects with the chorus, “Massa Purifoy! Father Purifoy!” Lucius/Jim Crow sings, “Maybe there’s a way that we can work this out. How I wish we had taken a different route. You can’t hide from the truth now there is no doubt. The least you could do is talk to me instead of leaving me to scream and shout!”

Immediately afterward, his father “tans his hide,” saying that he will deny his son forever. This sets the stage for the album’s title song, Jim Crow’s Tears, which ends the first act. He sings, “I look around and I see hate. Disguised by lies that say one day we will be free. How can I believe? That seems a joke to me.” Johnson is aiming for clarifying and redeeming moments in the second act, as each song directs Lucius and the others to realize how they can finally cast off the literal and figurative chains of oppression.

Underlying the dramatic lyrics is gorgeous musical accompaniment from an 11-member jazz band featuring the usual assortment of instruments and a nine-piece orchestra with strings and winds, conducted by Damien Crutcher. Johnson draws upon many jazz styles, classic and contemporary, inflected with Latin, spiritual, vaudeville, silky big band sounds, and occasional elements that are stark and minimalist. A virtuosic jazz trumpeter, Johnson also performs several solos.

There are many effective jarring choices in juxtaposing music with the lyrics, as in The Opening of The Minstrel Show song, an easy-going familiar tune layered on top of lyrics that alert listeners to the harsh indisputable realities being conveyed. And, then in the middle of the song, the mood and tempo change, adding dramatic tension. Johnson writes in his own liner notes, the objective of Jim Crow’s Tears is “to provoke reflection, dialogue, healing and positive change.” In several songs, including the opener as indicated above, Johnson switches quickly to another jazz form and the transition is effectively seamless. There is a natural spontaneity in every song and instrumental but Johnson also never lingers more than a few necessary moments to convey a specific musical idea. His versatility in composition never disrupts the clarity of the musical narrative’s arc.

The musical runs just under 66 minutes and it is a masterpiece of jazz verismo, as Johnson’s music always keep the focus on the dramatic impact of the singers’ expressions. It is a straightforward, robust, courageous testament to the unique vibrancy of Black American music and how it arose from oppression and formidable struggles of conscience, culture and politics.

Johnson quickly is making an outstanding mark on Salt Lake City’s music scene. A native of Detroit, he is in his second year as director of jazz studies at The University of Utah. A Shift West, his jazz commission for this year’s Utah Arts Festival, premiered to one of the strongest audience reactions of approval witnessed in recent years at the venue.

Johnson has a long, diverse portfolio of performances, having appeared on an impressive list of albums including two Grammy-nominated releases: Tony Bennett’s A Swingin’ Christmas and Karen Clark Sheard’s All In One. A trumpeter and arranger with the Count Basie Orchestra, he also was featured in the standup-comedy film Make Me Wanna Holla starring Sinbad. In 2012, Johnson received an ASCAP Herb Alpert Young Jazz Composers award and was selected as one of 25 Detroit performing and literary artists to receive a Kresge Artist Fellowship. He also is the former director of Detroit Symphony’s Civic Jazz Orchestra.

Jim Crow’s Tears was supported by New Music USA, made possible by annual program support and/or endowment gifts from the Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust, Helen F. Whitaker Fund and Aaron Copland Fund for Music.

A live performance of Jim Crow’s Tears will be presented March 10, 2017 in the Jeanne Wagner Theatre of The Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. For more information or to order the album, see here. The album also can be ordered through various sites including Amazon, CD Baby and Apple iTunes and individual tracks through Sound Cloud.

2 thoughts on “Kris Johnson’s album Jim Crow’s Tears is masterpiece of jazz verismo”