When the play Jump opens, the audience is enjoying the pithy, rapid banter between Erick, the young confident skydiver (Matthew Sincell), and Phil (Darryl Stamp), a 60-year-old first-timer, as they prepare for the fateful jump from 12,000 feet above the ground. The audience laughs as Erick tries to ease the nerves of Phil, who rattles off plenty of statistics and historical trivia about skydiving. The scene ends abruptly just seven minutes into the play. We learn that Phil did not survive the catastrophic malfunction of the tandem pair’s parachute.

There are other occasional points in Jump that elicit some nervous laughter among audience members. Most notably, these occur when Erick tries to charm Michelle (Nicki Nixon), the physician treating his injuries, or when he meets Phil’s widow Abigail (Teri Cowan) at a café. But, the play proceeds with many surprises. There is no gratuitous melodrama embedded in the gravity of the play’s striking epiphanies. And, as we witness just how intertwined the lives of the four on-stage actors truly are, Austin Archer, the playwright, presents an abundance of genuine emotions that brings tears from many audience members.

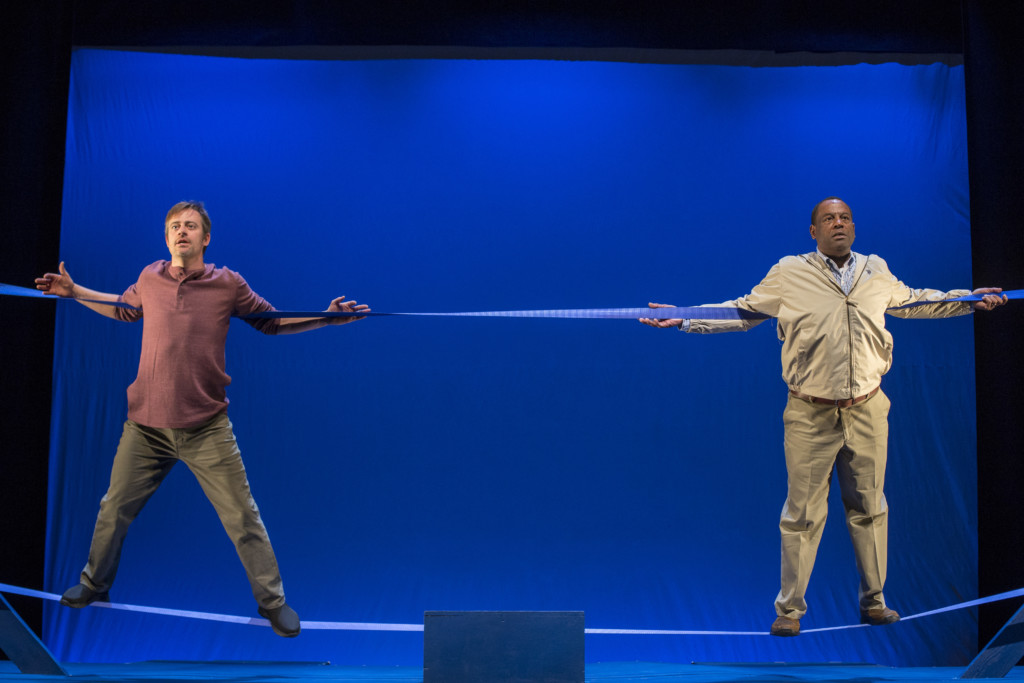

A co-production of Plan-B Theatre and Flying Bobcat Theatrical Laboratory, Jump is exquisitely crafted and executed on all measures. The play’s production expectations certainly were a challenge for two companies that individually have succeeded well at maximizing the leverage of minimalist production. But, in Jump, they achieve an admirable artistic synergy as the play whipsaws from the sky (in flashbacks) to scenes in Erick’s hospital room, the apartment whom he shares with Michelle and the café where he meets Abigail. The two-tiered set design is simple. The skydiving scenes are effectively realized with a pair of straps that stretch across the stage and the actors’ movements are choreographed to simulate the action convincingly, thanks to Flying Bobcat’s Alexandra Harbold and Robert Scott Smith, the co-directors of the production. Cheryl Cluff’s sound design, always spot on, completes the effect with the whoosh of wind, the roar of plane engines and the elements that represent the sensation of falling through the open air.

There are notable moments in every actor’s performance. As Erick, Sincell naturally modulates the self-assured, cocky tone one might expect from a man who has more than 2,400 skydives to his credit. When he discovers that the parachute is useless, he does not seem visibly panicked, as he prepares to absorb the hardest impact of the free fall in hopes of saving Phil (a maneuver that many expert skydivers deploy in case of a parachute malfunction in a tandem dive). Unfortunately, we learn that Phil likely died before the final impact.

Sincell’s body language and vocal tone shift progressively, portraying a hesitant, confused individual who doesn’t understand how anyone could have seen his actions as heroic or why he survived. One of the most prominent examples occurs late in the play in an exchange with his girlfriend Michelle, played by Nixon with utmost conviction as a hard-nosed doctor who vigilantly guards her emotions from spilling forward. Erick’s cocky charm initially attracts Michelle, as he recovers from his extensive injuries but their relationship is fraying, as both guard their emotional reticence.

When Erick tells Michelle about his chat with Abigail, Michelle talks about how some people try to cope with grief by doing things that do not make sense. Erick responds sharply, “Christ, Michelle, I know you think you’re being helpful, but you have no idea what you’re even talking about! You were not there!”

Up until this point in the play, Nixon has played the calm, tight-lipped demeanor to perfection but one now can see how she struggles to not let a dam of emotions burst. She tells Erick, “I know this can’t be easy for you, but you hardly ever talk about it.” Erick cuts her off, telling her that she doesn’t know. Michelle turns Erick’s response back on him: “You don’t know where I’ve been, what I’ve seen. You don’t know. And I am sorry that what you went through was difficult, but you don’t have a monopoly on trauma.” This is the first lapse we see in Michelle’s guarded persona. Archer is a solid economical writer, as he leavens every scene with good bits of foreshadowing that an attentive audience member notice. And, the actors carry these through in perfect pitch.

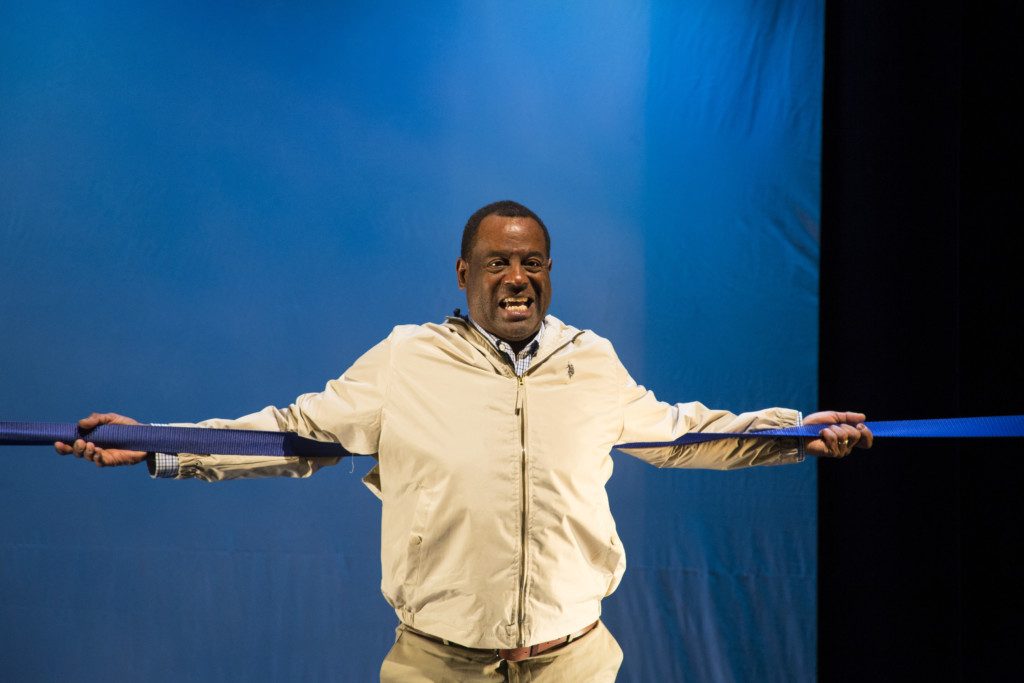

The most significant transformation is Darryl Stamp’s performance as Phil, a wonkish man who is more than visibly nervous about deciding to mark his milestone birthday with skydiving. In the initial scenes, Stamp’s nonverbal language accentuates the effect, which brings forth the audience’s loudest laughter. But, as the flashbacks reveal a profound portrait of a loving man who also is trying to make sense of a past inexplicable tragedy, Stamp gives the play its most stirring moments. Archer gives Phil two very short soliloquies toward the end – the first being “the great summation.” Stamp sets the simple, elegant, heartfelt cadence from the beginning of the passage: “Right now. This is it. This is the most important moment of our lives.” It resonates so strongly that the remaining portion of the play emanates Stamp’s tone even when Phil is not on stage.

Abigail, his widow, sets the platform as catalyst for the play’s intrinsic catharsis. Cowan’s natural enthusiasm exudes compassion and empathy. She visited Erick in the hospital while he was still unconscious and subsequently had attempted to contact him so that she could see him in person. She tried unsuccessfully to reach him by phone for six months and Erick finally finds the courage to answer her call. When they meet in the café, she is happy to hear that Erick is doing well and that he has met someone. She tells him that her son was engaged to a woman who was on her way to becoming a doctor.

Abigail is sincerely invested in alleviating Erick’s guilt for reasons that become clear shortly. She recalls her son: “He used to feel intimidated or like he wasn’t good enough and … ya know classic masculine inferiority complex. Anyway, the point is I’d tell him just not to worry about it. And neither should you. She’s a grown woman and she is choosing to be with you.” This exchange, which continues for several minutes, is the linchpin for every character’s epiphany.

There is unique poignance to Jump, the fourth in the series of works by Utah playwrights 35 and younger, who were tapped as commission winners by the David Ross Fetzer Foundation for Emerging Artists (The Davey Foundation). The Foundation was established after Fetzer’s sudden death at the age of 30, which happened just days before Christmas in 2012. Fetzer’s death was accidental, as an autopsy revealed that he had the equivalent of two glasses of wine and a critical threshold level of oxycodone (most commonly found in Percocet) in his body. An immensely talented and versatile actor, writer, musician and performer, Fetzer was well known in the Salt Lake City theatrical scene and had appeared in several Plan-B Theatre productions.

In fact, many people involved in this new production of Jump knew Fetzer directly or indirectly. Among the music featured in the production is the song titled Eddie’s Balloon, which was performed by the Mushman band to which Fetzer belong. The Jump producers also feature songs by Archer in the prelude to the start of the play.

But, thanks to the natural coincidence of creating new expressions, Archer’s play simultaneously is a tribute to Fetzer’s artistic legacy and a worthy theatrical meditation for anyone who struggles to find meaning in losing a beloved individual, regardless of the tragic nature of circumstances or whether it is sudden or foreseeable. Phil speaks at one point about the innate human senses of audaciousness and arrogance: “Too certain of ourselves to embrace the inevitable fact that sooner or later the chute is going to fail and the ground is going to come roaring up to meet us. I think that arrogant, unfailing optimism might just be my favorite thing about people.”

Rounding out the production is a first-rate crew: La Beene (costumes), Pilar I. (lighting), Cara Pomeroy (set) assisted by Iris Salazar, Arika Schockmel (props), and Jennifer Freed, stage manager.

Jump is presented in the Studio Theatre of the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. The only available tickets for the five remaining shows are for the 4 p.m. and 8 p.m. performances on Saturday, April 14. However, pre-paid wait lists will be available for the other performances (Thursday, April 12 and Friday, April 13, 8 p.m.; Sunday, April 15, 2 p.m.) will form in the Rose Wagner box office one hour before show time. Patrons must be present to be added to the wait list and then should plan on checking back five minutes before show time. As many wait list requests as possible will be seated at show time. Those who are not seated will receive a full refund. Typically, at least one person on the wait list (and often more) has been seated for a sold-out performance.

See Plan-B’s website for more details.