Misery, one of Stephen King’s best novels, is about an author’s deepest terror as he desperately tries to figure out how to stay alive, while he is imprisoned in the home of the woman who calls herself “his number one fan.” When the 1987 novel was adapted three years later into a film, directed by Rob Reiner in which Paul Sheldon was played by James Caan, it was Kathy Bates’ performance as the nurse Annie Wilkes and her horrifying bedside manner that convinced moviegoers that King’s story was about her.

In the stage version of Misery, a co-production by Immigrant’s Daughter Theatre and Lil Poppet Productions, we see a blend of the novel and film treatment in a dynamite interpretation featuring gripping performances by the three-actor cast, effectively set in a most unconventional space. Directed by Morag Shepherd, the production is staged in the basement of the Dolores Doré Eccles Ceramics Center at Westminster University. It turned out to be the apt venue for telegraphing the utter isolation and remote sense that Paul wonders if he will be able to escape alive.

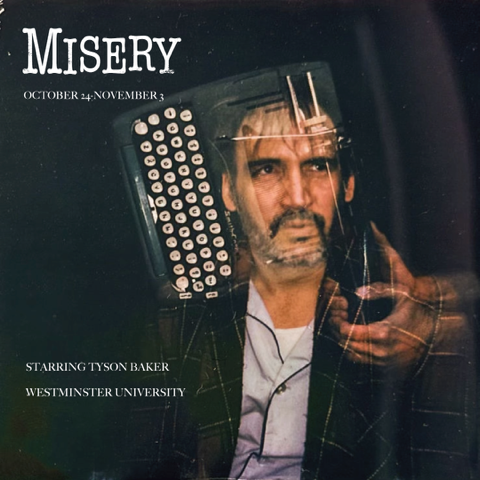

The stage version, with some very dark comedic elements, was written by William Goldman, one of Hollywood’s legendary screenwriters who also penned the adaptation of King’s original for the 1990 film. The play stays close to the film version, with one huge exception, but it also opens just as it did on the novel’s first pages. Paul (Tyson Baker) is heavily sedated with pain killers because of broken bones he suffered in an auto accident and is awakened by Annie (Stephanie Stroud) who speaks the story’s famous line, “I’m your number one fan.” In fact, as the audience enters the space before the start of the show, Paul is already in his hospital bed. We’re no longer just an audience. We are voyeurs who have no way of being shielded from the brutalities that we are about to witness.

In such close quarters for staging, with a minimalistic set that is just as resourcefully impactful as in other Immigrant’s Daughter Theatre productions, the audience is positioned to take in the full impact of the ordeal and its terrifying consequences. Baker and Stroud command every iota of our attention throughout the riveting 95-minute theatrical adventure. The most exceptional element of their performance comes in how they have shaped their respective character personalities without flattening them as cardboard monster caricatures. Likewise, in the handful of scenes critical to the trajectory of narrative tension, Alvaro Cortez completes the solid chamber acting ensemble as Buster, the sheriff who is intrigued by Annie’s unusually intense form of adulation for a celebrity author whom authorities knew has been missing for months.

The two leads meet the stage version’s most difficult tasks to emulate the horror punch brilliantly rendered in the novel and which is mostly achieved in the film. Misery is about Paul. He can’t stand to continue writing stories for the Misery Chastain popular fiction franchise that have brought him success and celebrity status. Yet, he can’t resist writing these books. He is a conflicted soul who loathes what he has become and despises the readers who have taken every installment in the series with great enthusiasm. He is conflicted about the fame even as he accepts it as validating himself at a particular moment. He also is newly addicted to the pain medications that Annie has given him. These conflicts converge in a perfect storm now that he is trapped by a woman claiming to be his greatest fan but who literally wants to cut away every part of him until there is nothing left that would otherwise keep him alive.

Baker and Stroud rise beautifully to the challenge, navigating a lot of surprising nuances that enrich, not flatten, the landscape of horror that has transformed the home of Annie Wilkes. The biggest criticism of Goldman’s stage version is the omission of Paul’s discovery of Annie’s scrapbook chronicling a nurse who is a serial murderer and has progressively become more evil in how she dispatches her victims. It is grippingly detailed in the novel and the film has a scene as well. In the film and stage versions, Annie mangles Paul’s legs with a sledgehammer. The novel has a bloodier experience: Annie cuts off one of his feet with an ax and severs one of his thumbs with an electric knife.

Yet, Shepherd, the three actors and the small production team achieve the essential sense of urgency in the stage version, which does not come as easily as it does in the novel or in the film adaptation. Baker convinces us just how desperate and terrified he really is. Even in Annie’s most brutal moments, Stroud signals to us how deflated and demoralized she feels, knowing how her most ardent sentiments for her favorite books literally have meant nothing. Having enjoyed the novel and the film version, this stage production brings the same effect. Once again, Immigrant’s Daughter Theatre chooses the smartest options in their staging.

The show closes Nov. 3.