An atypical but most enlightening cycle juxtaposing string quartets composed by Franz Joseph Haydn and Béla Bartók will come to a close in a March 25 concert by the Fry Street Quartet, as part of the NOVA Chamber Music Series’ gallery programs.

Two Bartók quartets – the lyrical second and the experimental fourth which employs numerous stringed instrumental effects – will be performed along with Haydn’s Opus 76, No. 1 in G Major, a prescient, experimental work in its own regard. The performance, scheduled at 3 p.m. in the G. W. Anderson Family Great Hall at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA), concludes a four-concert cycle series of the complete set of six string quartets composed by Bartók (1881-1945) and the six string quartets comprising Opus 76 by Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1809).

The Haydn-Bartók cycle has offered new perspectives for audiences as well as the members of the Fry Street Quartet. Haydn’s set of six Opus 76 quartets is a compendium which the precedent-setting master of the form completed in his middle 60s. He synthesized the elements that had distinguished the scores of string quartets he already had written and invented new approaches both harmonically and structurally that presaged the symphonies and string quartets Beethoven composed in the first quarter of the 19th century.

Bartók’s six string quartets cover a 30-year span of the composer’s career and his evolving experimental approach. To hear all 12 works over a two-year time in a focused presentation has primed audiences to learn about two composers whose lives differed so thoroughly in professional and emotional terms but yet they shared the objective of unconditional artistic independence borne by their experience in the same geographic region. Many ensembles tackle cycles of an individual composer’s string quartet oeuvre but few venture in juxtaposing the works of two composers, especially from different eras. As described in a preview last fall at The Utah Review, Haydn and Bartók are more precise blood relatives as musicians than what others have conventionally asserted.

“We’ve been going deeper inside the language and soul of both composers in this cycle,” Robert Waters, violinist, says in an interview with The Utah Review. The Fry Street Quartet is an internationally acclaimed ensemble that has been in residence at Utah State University’s Caine College of the Arts for more than a dozen years. Next year, the ensemble will begin a three-concert cycle highlighting Bartók’s six string quartets at the USU Logan campus and featuring Peter Laki of Bard College, one of the foremost scholars who has written on the composer’s music.

For NOVA, which is celebrating its 40th anniversary, Jason Hardink, artistic director, says the cycle is a pinnacle in the series’ history. “We are completely overtaken by what the quartet has brought to this project in playing some of the greatest chamber music repertoire,” he says. Waters graciously returns the favor, adding the experience has been a “great gift,” and “unbelievably fruitful.”

The selections defy neat categorization for both composers in this particular form of chamber music. Bartók’s String Quartet No. 2, first performed 100 years ago in Budapest, comprises three movements, written when the composer was in his mid-30s. There is an intense self-directed lyricism that alternates throughout the work between tranquility and unrequited brooding. In terms of movement structures, the first opens in a conventional classical sonata form but the music, especially in the main theme played by the first violin invokes the free-wheeling rhythmic and harmonic character of the folk music that Bartók absorbed so thoroughly.

The second movement is loosely based on the rondo form but its music, propelled by rhythmic virtuosity, captures the composer’s unique character in full force – from its resistance to being anchored in keys to its melodic inflection based on Bartók’s interactions with the music of the Berbers in north Africa. The final section of the second movement is a veritable storm marked Prestissimo which pushes the ensemble at a furious pace. The quartet’s final movement is an abrupt switch — a structure that even Bartók wrote as “difficult to define.” Bartók was a master of melancholic expression in music and it is best to let the final notes of the piece dissipate completely before responding with applause.

Written a decade later, the Fourth String Quartet takes Bartók’s radical experimentation with form to a new level. It encompasses five movements and his harmonic orientation is as fluid as it is astonishing in its musical colors and textures. For example, the second movement, marked Prestissimo, is played with mutes, described by Chris Darwin as “fluttering moths but with a variety of strange sounds – slithering semitones, slides and strums.” Meanwhile, the fourth movement, in an Allegretto tempo, requires pizzicato throughout it. The musicians whiten their sounds in the third movement without vibrato while in other instances the instrumentalists slide from one note to another. The quartet also features instances of the Bartók style of pizzicato, where the sound of the strings rebounds against the fingerboard.

The third movement is a stunning exploration of a nighttime mood, with the cello melody starting simply and gradually becoming more embellished while the other strings move through sustained chords that are progressively dissonant. The last movement, marked Allegro Molto, is the Bartókian invocation of a furiously exhilarating village dance.

Likewise, the single Haydn quartet featured to close out the cycle is Opus 76, No.1, which signals the sophisticated experimentation of so much of the composer’s last working phase of his life. Haydn moves extensively between G Major and G minor throughout the first and last movements. The second movement, in C Major, reveals Haydn’s famous gifts for intimate depth in his slow melodic writing.

In the third movement, while Haydn casts it as a minuet, he marks the tempo as Presto with a middle section highlighting a Ländler, the folk dance that foreshadowed the waltz. Haydn opted for darker colors as the final movement opens in G minor before returning to the work’s signature key in the closing pages of the quartet that echo folk dance music of the composer’s time. Nearly 130 years separate the works for this program but their positioning here emphasizes an innate trait of extraordinary musicians who were very much influenced by a region in eastern and Central Europe with which both were deeply familiar.

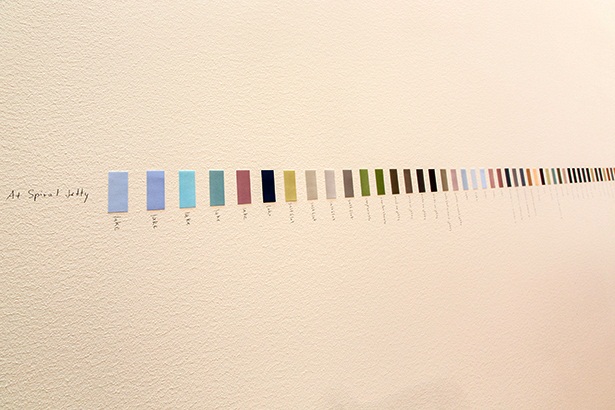

The setting for the last two concerts of the cycle has been the UMFA’s Great Hall, which Waters says has been relatively easy for the ensemble to adjust to for balancing the sound, given the venue’s spaciousness, high ceilings and natural light. The Hall houses the largest installation of Pantone samples by artist Spencer Finch, which represents a comprehensive study of field observations of the natural environment surrounding the Great Salt Lake.

Indeed, the setting accentuates the emotional character of this particular Haydn-Bartók string quartet cycle. In last fall’s Gallery Series concert, on a Sunday afternoon after a rainstorm, the natural light changed periodically – sometimes brightening with the mid-afternoon sun and then darkening a few minutes later because of lingering clouds. And, nature acting as its own lighting designer makes for perfect moments. Waters recalls how the natural light darkened at precisely the moment when the music in Bartók’s first string quartet transitioned to one of the work’s most heart-wrenching moments.

For more information, tickets and series subscriptions, please visit NOVA’s website.