The absorbing, intricately structured documentary Public Trust opens with a majestic, joyous montage of America’s public lands, accompanied by stirring orchestral music and narrated by journalist Hal Herring. However, the film quickly segues into the public land debates, which are anything but majestic or joyous. These lands, Herring says, are as quintessential to the American experiment of democracy as the Bill of Rights and the U.S. Constitution.

Directed by David Garrett Byars, whose No Man’s Land three years earlier chronicled the 41-day occupation in 2016 by Ammon Bundy and his anti-conservation followers at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, Public Trust delivers all of the possible incisive urgency surrounding the politics of public lands with synergizing clarity.

Public Trust will be screened in a livestream event by the Utah Film Center on Wednesday, June 24, at 7 p.m., just one day after the No Man’s Land screening. Following the Public Trust screening, Byars will join the discussion with moderator Doug Fabrizio from KUER-FM’s RadioWest program. The livestream link for the event can be found at the Utah Film Center Vimeo website.

Utahns certainly will want to follow this film, which premiered at the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival last winter in Missoula, Montana. The documentary was made possible with the support of executive producers Robert Redford and Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard.

The film captures the dynamics of a race against time for political strategists on both sides. The newest film focuses on how conservation efforts achieved during the Obama Administration for Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument, Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness have been systematically undone during the Trump Administration.

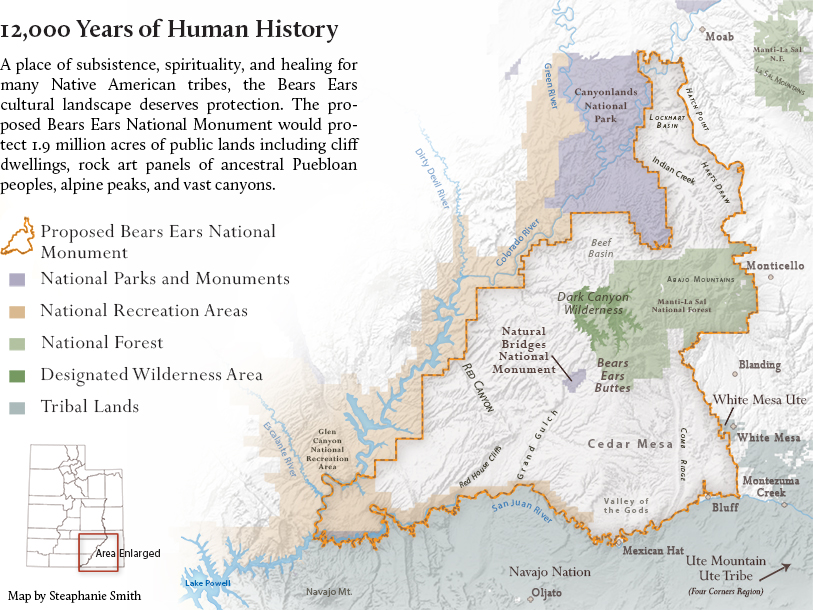

Byars astutely picked the right trio of sites to illustrate the breadth and depth of what is at stake for the nation’s public lands. As previously noted in The Utah Review, the campaign for designating Bears Ears – an area encompassing nearly 2 million acres in southern Utah – as a national monument under the U.S. Antiquities Act of 1906 has commanded attention from across the country for many reasons. It was an unprecedented effort, as a coalition of five tribal governments – Navajo, Hopi, Ute Indian Tribe, Ute Mountain Ute, and Zuni – have been centrally involved. Previously, Indigenous tribes have been consistently excluded or relegated to the back bench when it comes to discussing public lands.

The Gwich’in in Alaska have taken front and center in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge efforts, as the film shows the holistic dimensions of the Refuge as their way of life and the necessity of protecting the Porcupine Caribou and other wildlife species. In Minnesota, the Boundary Waters campaign similarly represents the rollercoaster effects of the long game involved in preserving the area, with setbacks occurring right on the heels of exhilarating relief and triumph.

Herring, who also appeared in No Man’s Land, guides the viewer through the threats and efforts of the Trump administration to undo systematically these monuments and open the areas to unregulated commercial, mining and extraction purposes. One of the most telling comments is from Alaska, where residents for decades had become accustomed to receiving generous royalty checks because of drilling and mining on the public lands. Indeed, the notion of “it’s akin to a heroin addict getting a fix” sums it up tightly.

As for Bears Ears in Utah, the film frames the counterpoint by featuring Angelo Baca, a Navajo/Hopi filmmaker, and several Republican members of the Utah Congressional delegation who have pushed not only for downsizing significantly the monument designation but also for returning control of public lands to the state. U.S. Rep. Rob Bishop, who is retiring this year and is a candidate for lieutenant governor in Utah on the Thomas Wright ticket, is unconditionally dismissive of even talking with Bears Ears interest groups. Byars accurately portrays former U.S. Rep. Jason Chaffetz, who now appears periodically as a Fox News commentator, as a callous buffoon with awkward Orwellian tendencies.

When President Trump came to Salt Lake City after announcing that he would minimize the Bears Ears designation to a fraction (15%) of what was indicated in Obama’s 2016 proclamation, Chaffetz wrote, “The notion that our only option for managing public land is a restrictive monument designation is false. In truth, we can build bathrooms and fire pits, and accommodate hunting, fishing, grazing, and permit accessibility without destroying the land. In places where restrictive conservation rules are less justified, we can even authorize responsible resource extraction.” Indeed, this mantra reverberates in Minnesota and Alaska as well among the anti-conservation interests.

One of the most important takeaways from Public Trust is the spectrum of supporters involved in conservation efforts. Unlike ranchers such as Cliven Bundy and those who illegally occupied the Malheur Refuge, ranchers who are featured in the film express their gratitude for being able to rent at a low, affordable cost grazing rights on public lands and they reassert their responsibility in conserving the integrity of public lands.

As recalled in the film, when Chaffetz had proposed twin bills in the U.S. House to, one, immediately allow the U.S. Department of Interior to sell off 3.3 million acres of public land, and, two, to strip the Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service of their law enforcement powers, in the aftermath of the Malheur occupation, the group Backcountry Hunters and Anglers sprung into action to derail Chaffetz’s proposals as quickly as possible. The campaign included the social media hashtag #keepitpublic. The opposition was so fierce that Chaffetz relented and posted an image of himself in hunting gear and holding a dog (a portrayal that the sports industry group laughed off as unbelievable and preposterous), along with the hashtag #keepitpublic.

As with so many other issues, the future of Bears Ears rides on an existential stake in the forthcoming presidential election. While nation was focused on the pandemic and the protests led by the Black Lives Matter movement in every state, the president signed earlier this month yet another executive order to expedite pipeline construction by waiving the environmental review mandated under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Meanwhile, there are three pending lawsuits involving Utah monuments (Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante), which are supported by the InterTribal coalition, Utah Diné Bikéyah, the Natural Resources Defense Council, Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, Earthjustice and Patagonia. A court decision is possible before the election in November.

Just as vivid in the film are the circumstances in the Arctic refuge, as shown in exceptional and emotional moments with Bernadette Demientieff, executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee. Alaska’s Congressional delegation – all Republicans – has resisted the Indigenous claims with the same dismissiveness as observed with Utah politicians. Viewers see U.S. Rep. Don Young speaking just as callously as his colleague, U.S. Rep. Bishop. Likewise the state’s two U.S. senators – Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan – are just as resistant to the voices of the Gwich’in and their supporters.

However, in news arriving after the film was released in February, two of the nation’s largest banks – JPMorgan Chase and Co. and Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. – signaled that they reassessed the public risk management factors and recommended that no direct funding for oil and gas development in the Arctic be approved. And, with the pandemic and the recent economic downturn, the process has stalled.

Meanwhile, in Minnesota, Spencer Shaver has worked tirelessly to oppose a copper mine that he says could pollute the Boundary Waters with consequences as devastating as what has been observed in the Berkeley Pit in Butte, Montana. Again, the race against the clock is key in this region just as well. Earlier this month, a consortium of conservation groups went to court to challenge the administration’s decision to renew 13 prospecting permits that would open the door for Twin Metals to go forward with the sulfide-ore copper mine at the edge of the Boundary Waters site in northern Minnesota.

Byars’ film, edited with bracing impact, arrives at the right moment, as the country’s political awareness and engagement have surged to levels that have not been seen for decades. Republicans who are backed by corporate interests have become desperate and are trying to race into stages where the risks to the integrity of public lands could lead to irreversible damage. Ryan Zinke’s tenure as U.S. Secretary of the Interior proved that corruption was boundless. And, his successor, David Barnhart, appears determined to complete the job. There are those who would repeal the U.S. Antiquities Act of 1906. However, no decision would be more utterly rash and foolish than to cede the control of public lands to the states. From every sobering point of financial, management and logistical consideration, no state could feasibly or responsibly handle the task. So, state politicians would quickly defer to selling off the lands to private interests, almost certainly ensuring not just environmental ruin but also financial catastrophe for its respective residents. Public Trust covers all of these dangers.

Returning to Bears Ears for a moment, as The Utah Review noted in 2016, John Freemuth, a Boise State University public policy professor and former park ranger, explained in an interview with Fusion, the Antiquities Act is being used to help “complete the American story.” That is, not as a commemorative gesture but rather as a strategic step toward ending the systemic ignorance of issues and topics in the country which point to the rights, vitality and viability of Indigenous Americans. These steps include full-throated respect for tribal sovereignty and sacred religious beliefs and practices as well as bringing Indigenous voices into writing the nation’s inclusive, honest and accurate history.

Byars, who also amplifies the voice of Herring in Public Trust, extends that unique American story to its all-encompassing expression of the core freedom signified by the designation of public lands and all of the rights associated with it—the work in progress of the American experiment in moving toward freedom in its most comprehensive sense.

Roka twice refers to efforts to “return” control of the Public Lands to the states — thereby accepting a false framing of the issue. The Public Lands were NEVER state’s lands and the states, when they accepted statehood, foreswore any claim to the lands. American Indians can seek return of the lands, but not the states; the states never had them. The Public Lands are a legacy entrusted to the American people at large and administered by the Federal Government.