carry my message. carry my hope. carry its meaning. carry it home.

carry my depression. carry disconnection. take this suspension.

carry the clone. hop in my step. camera in my bag. calm in my soul. pen in my hand.

‘Pen In My Hand’ – Parallax song from the demo ‘Landlocked,’ lyrics by Blake Donner (c. 2001-2002)

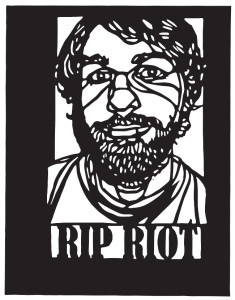

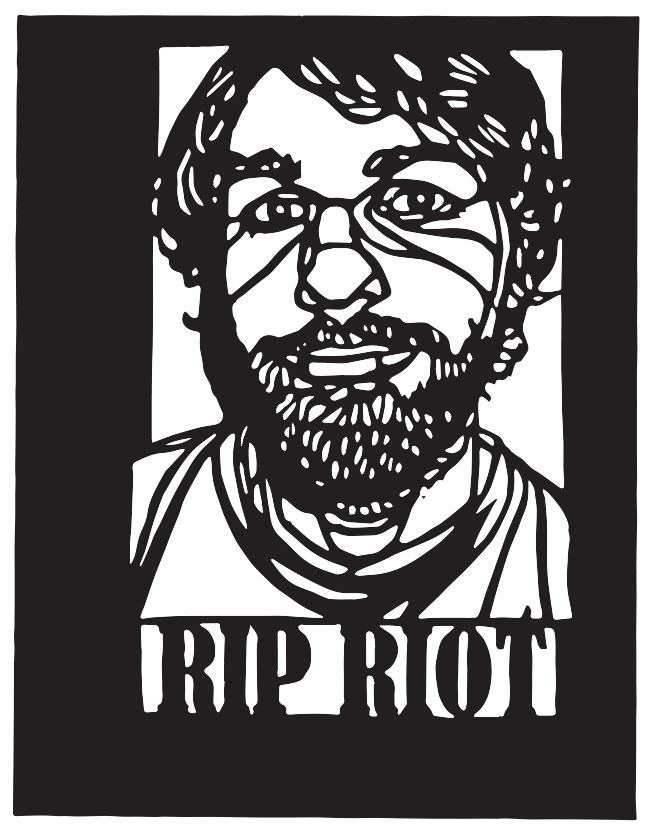

‘It leaves me craving something else, somewhere else. It makes me long for a RIOT.’ — Greg Bennick (RIOT was Blake Donner’s graffiti persona).

When Blake Donner started his zine The Fifth Goal in 1998, he was 17, immersed in his journey for Hare Krishna consciousness. “He was completely dedicated, almost like a zealot,” his mother Laura Hamblin recalls.

When Blake Donner started his zine The Fifth Goal in 1998, he was 17, immersed in his journey for Hare Krishna consciousness. “He was completely dedicated, almost like a zealot,” his mother Laura Hamblin recalls.

However, by 2001, when he was working on The Fifth Goal’s fourth issue, which pivoted almost exclusively toward the historical exploration of railroad graffiti art and culture in North America, Donner already had left behind the Krishna path after experiencing an existential crisis. “Blake called me up late one night from San Francisco,” Hamblin, who is a poet and is on the English department faculty at Utah Valley University, recalls. “He had gone to see the temple president about what path he should take. When the president told him, ‘I’ll tell you,’ Blake said, ‘This is bogus and I am coming home.’”

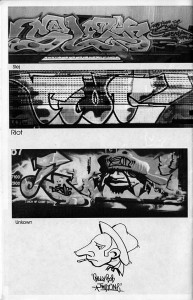

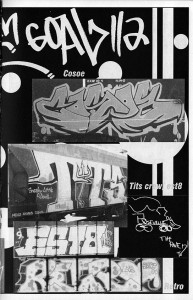

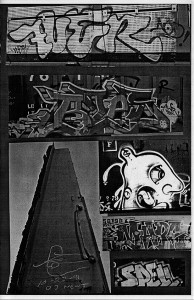

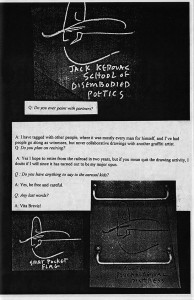

Suddenly everything shifted for Donner, as Hamblin explains. His spiritual journey turned to an exhaustive artistic exploration of freight train graffiti, represented in zine issues that were produced in cut-and-paste form with stark back and white photocopy printing. While the first three issues included a fair amount of content on the subject, the final five issues of The Fifth Goal would comprise a rare, first-hand discovery of chalk drawn monikers, images, and drawings of hobos, trainworkers, trainhoppers and transients scattered across North America.

Suddenly everything shifted for Donner, as Hamblin explains. His spiritual journey turned to an exhaustive artistic exploration of freight train graffiti, represented in zine issues that were produced in cut-and-paste form with stark back and white photocopy printing. While the first three issues included a fair amount of content on the subject, the final five issues of The Fifth Goal would comprise a rare, first-hand discovery of chalk drawn monikers, images, and drawings of hobos, trainworkers, trainhoppers and transients scattered across North America.

Donner also included interviews with graffiti artists along with contributions by Bill Daniel, who directed the outstanding 2005 documentary ‘Who is Bozo Texino,’ a film incorporating 16-mm and super 8 black-and-white footage that investigates the origin of an ubiquitous yet mysterious freight train tag of a character that’s drawn wearing a cowboy hat with a pipe. Daniel and Donner corresponded frequently, exchanging photographs and materials. The Fifth Goal features some of Daniel’s photographs and some of his own graffiti and tags. Daniel dedicated his 2008 book ‘Mostly True: The Story of Bozo Texino,’ basically a printed transcript of his documentary film along with new material, to Donner’s memory.

The compilation of all eight issues of The Fifth Goal is in a new book titled ‘The Fifth Goal 1998-2003: Transcendental Graffiti Zine,’ which has just been published jointly by Division Leap of Portland, Oregon, and Hierophant, based in Salt Lake City.

The compilation of all eight issues of The Fifth Goal is in a new book titled ‘The Fifth Goal 1998-2003: Transcendental Graffiti Zine,’ which has just been published jointly by Division Leap of Portland, Oregon, and Hierophant, based in Salt Lake City.

It is a tribute to Donner, a young Renaissance man with many interests who also was the lead singer for the hardcore punk band Parallax. Donner, who was 24, and three of his friends died in the summer of 2005 when they tried to swim to an underground chamber through an underground passageway in a cave near Provo, Utah. At the time of his death, Donner was working on a debut album for Parallax with Counterintelligence Recordings.

The book already is drawing rapidly growing interest, even before its formal release at Printed Matter’s 2015 Los Angeles Art Book Fair, which runs January 29th through February 1st at the Geffen Contemporary at Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA).

Early orders already have exhausted the first print run and pre-orders are now being taken for a second run, which will ship in early March. All proceeds from the 436-page trade paperback book, which is priced at $25, will be donated to the Donner/Galbraith Scholarship Fund at Utah Valley University in Orem.

Early orders already have exhausted the first print run and pre-orders are now being taken for a second run, which will ship in early March. All proceeds from the 436-page trade paperback book, which is priced at $25, will be donated to the Donner/Galbraith Scholarship Fund at Utah Valley University in Orem.

The book is a magnificent embodiment of the artistic impulses which become possible in the Utah Enlightenment. Also included are essays and texts by various contributors and editors who knew Donner as well as those discussing the author’s interest in freight train graffiti along with his cultural influence and impact in Utah, where he lived. The Fifth Goal compilation includes contributors Travis Low and Adam Davis, Kate Davis, Greg Bennick and Hamblin.

Donner was unconditionally courageous, forever restless, and insatiably curious in his art and music and he left an indelible imprint upon the artistic souls of friends as well as those who only heard about his work long after his accidental death nearly ten years ago.

Travis Low, a documentary filmmaker and a bookseller at Ken Sanders Rare Books, writes in one of the essays, “Since Blake has been gone I’ve grown and changed a lot. I’m 30 years old now. Blake was only 24 when he died. I was 20. It has been nearly 10 years since his death, and I only knew him for a total of 5 years. None of it seems real. Blake still feels like an older brother and mentor. He still teaches me things through the messages he left in his art and music.”

Travis Low, a documentary filmmaker and a bookseller at Ken Sanders Rare Books, writes in one of the essays, “Since Blake has been gone I’ve grown and changed a lot. I’m 30 years old now. Blake was only 24 when he died. I was 20. It has been nearly 10 years since his death, and I only knew him for a total of 5 years. None of it seems real. Blake still feels like an older brother and mentor. He still teaches me things through the messages he left in his art and music.”

One of the many significant aspects of Donner’s work in The Fifth Goal is how he presents a substantial, rock-solid justification for graffiti’s artistic merits and aesthetic, especially in celebrating the venerable tradition of chalk drawings that have adorned freight train cars for many decades. In fact, as Low indicates, Donner’s own drawings using his moniker of ‘RIOT’ can still be found on railroad cars. “Once in a while, I find a RIOT tag hiding here or there,” he writes, “or if I get lucky I’ll catch a glimpse of one of the colorful and elaborate pieces that he painted on the side of a passing boxcar.”

Donner also featured interviews with artists who amplified his theme about the value and relevance of graffiti, especially in the medium of chalk. One of the interviewees talks about graffiti making in terms of a “symbiotic relationship [that should] not be disruptive [or] malicious.” Another responds to Donner, “It wasn’t meant to be provocative proselytizing for revolution but merely boxcar icon sloganeering as an equilibrium device for my own sanity.”

Donner also featured interviews with artists who amplified his theme about the value and relevance of graffiti, especially in the medium of chalk. One of the interviewees talks about graffiti making in terms of a “symbiotic relationship [that should] not be disruptive [or] malicious.” Another responds to Donner, “It wasn’t meant to be provocative proselytizing for revolution but merely boxcar icon sloganeering as an equilibrium device for my own sanity.”

Indeed, Donner’s legacy was not on the verge of disappearing or being relegated to a mere footnote in Utah’s cultural history, as Low discovered serendipitously in 2012 during a bookseller’s seminar in Colorado. Adam Davis (of Division Leap) spoke at the event, reminiscing about his formative adventures in book collecting and selling. As Low recalls in an essay in the book, “Later that night I saw Adam at a group dinner and I introduced myself. When I told him I lived in Salt Lake City, he immediately asked if I’d ever heard of a zine called The Fifth Goal. At the time he had no idea that I knew Blake. As it turns out, during one of Adam’s many days of digging through old boxes of books and paper, he found some copies of The Fifth Goal.”

As Low recalls, Davis had tried unsuccessfully to find people in Utah who knew about the zine before they met. He had been impressed by what he had seen and soon the two developed the plan that would lead to the new book.

As Low recalls, Davis had tried unsuccessfully to find people in Utah who knew about the zine before they met. He had been impressed by what he had seen and soon the two developed the plan that would lead to the new book.

“Freight train graffiti is difficult to document. There are good graffiti zines, but there is something that gets lost in color reproductions on coated stock, and identical grids of boxcar photographs,” Adam Davis explains in his essay for the book. “The Fifth Goal is something different. Beginning with the fourth issue, the simplicity of the zine began to mirror the beautiful and necessary economy of the old tradition of chalk drawings which it portrays. It’s easy to imagine the contrast slowly being pushed to the maximum setting as the zine unfolds and the photographs become starker and emptier.”

The first two issues of The Fifth Goal are ambitious projects. There are product and music reviews, ample photographs of railroad graffiti, some contributed material including recipes and Donner’s candid perorations about the search for full consciousness with spirit and soul, as embodied in Krishna philosophy. By the third issue’s publication in 1999, Donner already was immersing himself in the do-it-yourself aesthetic that defines a classic zine’s capacity for art unfettered from commercialism.

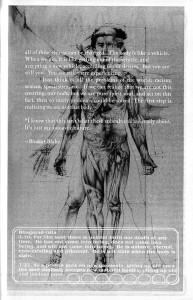

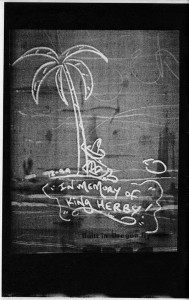

The fourth issue is the marvelous turning point in Donner’s emphasis, one that merges social, cultural, political and spiritual elements in the best manner of artistic criticism and history. He wrote, “Graffiti is what attracted [me] to spend time in train yards. When I first had the courage to walk the lines (around 1993) very rarely would I see any pieces of throwups. The first real graffiti I noticed were tags. John Easely, Sahl, The Rambler, Colossus of Roads, Herby, Water Bed Lou, etc. Most of which existed or continues to exist independently of the aerosol scene. Now a lot of the spray paint artists have crossed over, doing sketches as well as continuing to use spray paint. With all of this going on in the freight train scene, I rarely see any zines dealing specifically with the original aspect of freight train graffiti art. Some sketches date back to the 1960’s. Colossus tells me it has been going on since the Civil War. Hopefully it will continue as it seems to be doing. Most of what you see has been taken from Utah train yards. . . Be careful.”

The fourth issue is the marvelous turning point in Donner’s emphasis, one that merges social, cultural, political and spiritual elements in the best manner of artistic criticism and history. He wrote, “Graffiti is what attracted [me] to spend time in train yards. When I first had the courage to walk the lines (around 1993) very rarely would I see any pieces of throwups. The first real graffiti I noticed were tags. John Easely, Sahl, The Rambler, Colossus of Roads, Herby, Water Bed Lou, etc. Most of which existed or continues to exist independently of the aerosol scene. Now a lot of the spray paint artists have crossed over, doing sketches as well as continuing to use spray paint. With all of this going on in the freight train scene, I rarely see any zines dealing specifically with the original aspect of freight train graffiti art. Some sketches date back to the 1960’s. Colossus tells me it has been going on since the Civil War. Hopefully it will continue as it seems to be doing. Most of what you see has been taken from Utah train yards. . . Be careful.”

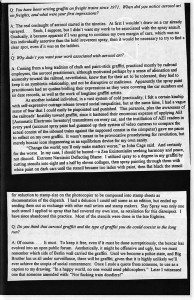

In 2002, Donner published three issues of The Fifth Goal, comprising an astonishing collection of graffiti art examples from many artists, emphasizing just as one of the individuals he interviewed says, how it reveals the ways in which the “boxcar has evolved into an open public forum.” There are various captures of the iconic Bozo Texino tag with lines such as “Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Politics” and “Acute Psychological Distress.”

There are tags from admirers acknowledging The Fifth Goal and Donner in his own ‘RIOT’ moniker. He explored various hand drawing styles, the influence of hip hop culture and the crossover into aerosol spray paint techniques. The eighth and final issue came out in 2003, delayed by the workload he carried for his college studies and the fact, as he indicated at the beginning of the issue, that he was being hunted down as a ‘vegan graffiti terrorist.’ Donner also mentioned that he had hoped to release future issues on a more frequent schedule. Nevertheless, the work he already had published constituted one of the most in-depth examinations in print of graffiti art on freight train cars.

There are tags from admirers acknowledging The Fifth Goal and Donner in his own ‘RIOT’ moniker. He explored various hand drawing styles, the influence of hip hop culture and the crossover into aerosol spray paint techniques. The eighth and final issue came out in 2003, delayed by the workload he carried for his college studies and the fact, as he indicated at the beginning of the issue, that he was being hunted down as a ‘vegan graffiti terrorist.’ Donner also mentioned that he had hoped to release future issues on a more frequent schedule. Nevertheless, the work he already had published constituted one of the most in-depth examinations in print of graffiti art on freight train cars.

Donner’s sense of prose and poetry matured quickly in his work. He wrote, “But the trains are always there. Silent, but screaming at me. The yards are where I find peace. I still yearn for expression, although I may not always know what I am expressing. This is my attempt.” Donner clearly had left behind Krishna philosophy but he had found a far more satisfying substitute for developing his spiritual conscience. Hamblin says she knew almost from the moment her son was born that he was an “ancient soul.”

Low emphasizes the historical value of Donner’s work in one of the essays which accompany the zine compilation. He writes, “The stark black and white xerox print captures chalk monikers better than anything outside of the actual train yards. Not only did Blake tirelessly troll the railroad lines and mail art networks for photographs of these rare pieces, but he also tracked down the artists for interviews to print alongside their tags…no easy task!”

Greg Bennick, one of the contributors for the new book, sees The Fifth Goal as a “powerful living legacy” for an extraordinarily talented artist who only was beginning to emerge before he was tragically taken away from the time in which he would have been able to develop his gifts. Bennick says, “The Fifth Goal represents a desperate and successful attempt to capture a slice of Americana that is often relegated to the dust bin: graffiti and how it stands as a valuable voice for those who otherwise would not be heard.”

Greg Bennick, one of the contributors for the new book, sees The Fifth Goal as a “powerful living legacy” for an extraordinarily talented artist who only was beginning to emerge before he was tragically taken away from the time in which he would have been able to develop his gifts. Bennick says, “The Fifth Goal represents a desperate and successful attempt to capture a slice of Americana that is often relegated to the dust bin: graffiti and how it stands as a valuable voice for those who otherwise would not be heard.”

Donner’s accidental death in a cave on a late August evening a decade ago brought a major outpouring of grief and sadness. “After Blake died, his band, playing without him, did a show in Seattle which ended in over a hundred people sobbing and hugging one another in the venue,” Bennick recalls. “The love for him, and loss of him was so tangible, so real. Not one bit of that love has been lost over the last ten years.”

The book’s publication is a testament to the immortality of the renegade spirit. As Bennick explains, “Blake was a renegade, a punk rocker, a seeker of truth. He explored the world at night while we slept. He delved into his expression while we dreamt. And when we woke up we found the world slightly transformed in his image.”

The book’s publication is a testament to the immortality of the renegade spirit. As Bennick explains, “Blake was a renegade, a punk rocker, a seeker of truth. He explored the world at night while we slept. He delved into his expression while we dreamt. And when we woke up we found the world slightly transformed in his image.”

Book orders are being taken here.

Additional information about Donner’s work also can be found here and here.

Blake was a great friend. Spent many hours discussing Boxcar Art with him, then got to meet in 2002 in Nor Cal.

Held a strong wholesome interest in the hobo graffiti culture. I had the pleasure of doing a profound interview with him years ago as well.

I miss you brother.