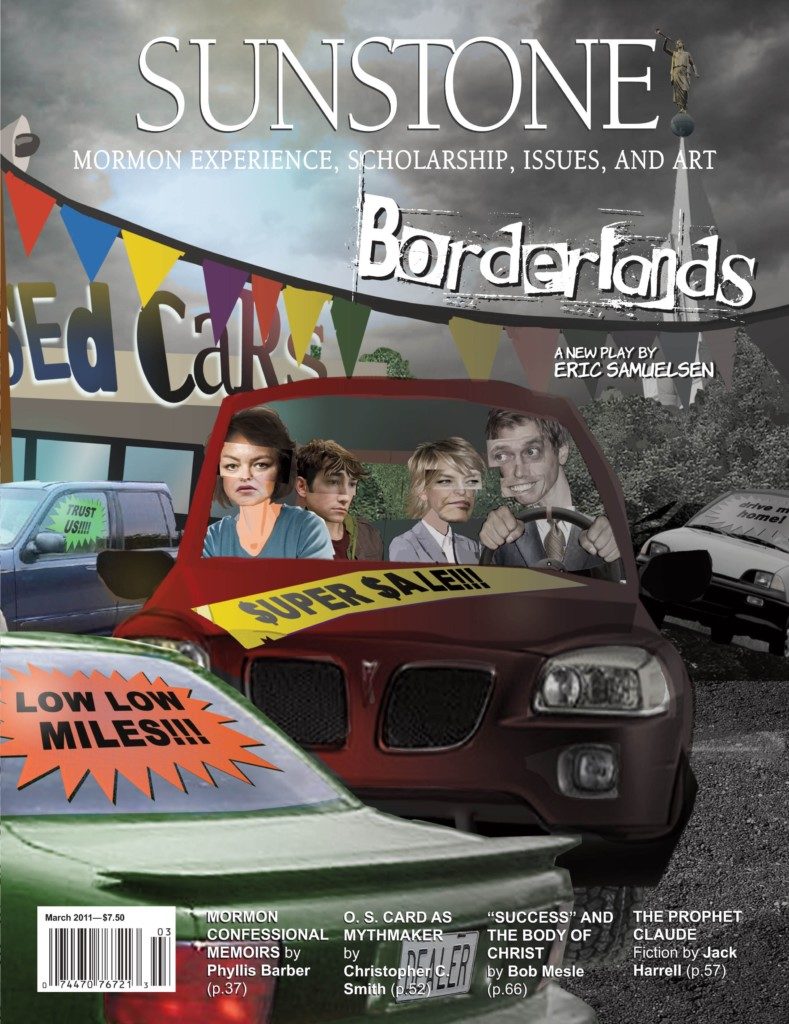

NOTE: Plan-B Theatre will present a free reading of Eric Samuelsen’s Borderlands, featuring the original cast of the 2011 premiere, on Oct. 5 at 2 p.m. in the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. While the performance is free, tickets are required and can be obtained at this Plan-B page. For details about funeral services and contributions, see the links at the end of this feature.

Eric Samuelsen, who died Friday at the age of 63 after a long illness, always will be a titan of the Utah Enlightenment. He epitomized and clarified how this spiritually abstracted movement of creative expression arising from Utah’s unique sense of place and meaning could be defined. Samuelsen did more than create extraordinary plays for the purpose of “art for art’s sake.” His plays elevated the contemporary experience – with the sum of its tensions, problems, conflicts, disappointments and crises – to an enthralling sensation of healing and empowerment.

He was one of the most dynamic figures in Mormon and Utah’s literary scenes, as his record has been summarized by the Association for Mormon Letters. Given his Norwegian family roots and his fluency with the language, he became a distinguished scholar of Henrik Ibsen’s works. At Brigham Young University, he prepared a new generation of some of Utah’s most courageous creators in theater. Unquestionably, the Samuelsen legacy will be nourished and expanded under the aegis of Plan-B Theatre, where he became a playwright in residence after his medical retirement from the university.

BORDERLANDS

An elucidating starting point comes from a 2011 Plan-B production that proved to be one of the most successful in the company’s history. In one of Borderlands’ best scenes – when all four characters are sitting in an ‘honesty car’ on a used car lot in Provo during a rainstorm – the individual and collective struggles to identify faith’s higher sense of purpose and its capacity for genuine compassion boil into a dramatic mix of despair and disappointment. Dave (Kirt Bateman) – who calls the vehicle a ‘sort-of Mormon car’ – is a used car salesman. He also is a disgraced, disbarred attorney convicted of embezzlement whose 18-year marriage ended amidst an adulterous affair and who, despite being once a Mormon bishop, has been excommunicated from the church. Gail (Stephanie Howell), an Amway distributor, is separated and refuses to admit or to discuss her deep reservations about her son’s impending mission call. At 17, Brian (Topher Rasmussen) is a self-taught mechanic who also is Gail’s nephew from California and is a member of the church’s Aaronic priesthood. His parents in California ‘exiled’ him to Utah in the hopes that he could overcome his newly acknowledged gay orientation.

However, the play’s most significantly strategic character is Phyllis (Teri Cowan), the stoic, efficient office manager of the used car business who took in her brother Dave when he was down and out and who tries to manage the pain of her terminal cancer. Phyllis, whom we learn lost her two young children and her husband in a tragic accident involving a drunk driver, perfunctorily goes about her expected duties as a Mormon in good standing but she also is bitter about the earthly return on that investment. She says, “They believe in false doctrines, don’t they? People in the world. Worldly people.” Even as the others continue their discussion, she sputters out, “All manner of falsehood,” and “Falsehood and wickedness!”

Cowan’s interpretation of Phyllis provided the high acting marks of this production, directed by Jerry Rapier. Her body language armor, with crossed arms and tightly pursed lips, crumbles into an emotionally inconsolable, pain-stricken heap during the play’s starkest moments of the final 15 minutes. With Phyllis and Brian, the instrumental faith issues delved straight to the moral epiphanies of Borderlands. Phyllis seems resigned to the intransigent inadequacy of religion’s capacity to soothe the pain of tragic death – a shortcoming definitely not limited to Mormonism. Brian, meanwhile, is trapped between literalism and dissent. In his still tender formative years, he already senses the prospect of ecclesiastical betrayal even as he hopes for a progressive gesture of affirmation and acceptance in a church he knows and loves. The juxtaposition of their dilemmas at the end leads to the most poignant open ending imaginable.

In the intimate Studio Theatre of the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts, Cowan’s Phyllis engulfed the space with such dramatic power that, on opening night, the cast at final curtain was visibly and genuinely moved in the emotional impact of Samuelsen’s closing scene. Every performance of the original run sold out, as did every performance that was added. At the time, it was Plan-B’s fourth-highest grossing show in its 20-year history. Borderlands entered an elite group: Hedwig and The Angry Inch, The Laramie Project and Facing East.

When word spread last week that Samuelsen was in end-of-life hospice care, many shared their thoughts and experiences on social media so that family members and close friends could read the messages to him. For the young actor Rasmussen, the Borderlands experience of portraying Brian had made a most profound impact. In his own Facebook tribute, he wrote: “As a confused, angsty, ambivalent teenager trying to navigate my way out of the LDS church, Eric Samuelsen held space for the ambiguous and painful questions I was living through. Borderlands caught me in the early stages of my development as an actor and as a human being. It was a privilege to be included in such a difficult conversation and to be welcomed into a diverse community of Utah artists. I often felt unsure at that time, afraid to offend, deeply torn. The character Eric had written, Brian, confronted things I didn’t have the words or confidence to confront.”

A UNIQUE PARTNERSHIP

Samuelsen’s bonding with Plan-B Theatre proved to be one of the most extraordinary relationships in Utah theater history: nine world premieres, Script-in-Hand readings of two of his Ibsen translations, one radio show and eight short plays. In a comprehensive essay published in 2015 at BYU Studies Quarterly, Callie Oppedisano summarized the relationship perfectly:

“Never before has a Mormon playwright so successfully partnered with a professional theatre company to produce so many new works. These works are influencing the Mormon theatre canon and assisting in the evolution of the Mormon theatre aesthetic. Samuelsen is demonstrating that Mormon theatre is becoming more dramaturgically diverse. His work is influenced by other countries, languages, and genres; it takes a hard look at politics and economics and the culture from which they come. His art form is capable of playing to a seasoned critical audience, one that leans toward the belief that theatre can and does lead to social change.”

Samuelsen’s first experience with Plan-B came more than 15 years ago, when he participated for several years in the company’s annual SLAM event. Playwrights had 24 hours to create and produce a 10-minute play. Some plays were ephemeral exercises but a few led to fully developed works that have anchored the company’s exceptional capacity to produce original works by Utah playwrights. Samuelsen’s SLAM entry from 2004, as Oppedisano recalls, was about a rancher-turned-beef-producer, partly inspired by Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation. Rapier asked Samuelsen to expand it and Miasma premiered in 2006, a play, as the company described, that synthesized “the grim realities of contemporary agribusiness, the evolution of the traditional American West, illegal immigration, homosexuality, apocalyptic Christianity, drug trafficking and corporate culture.”

The success of plays in the early years of the Samuelsen relationship with Plan-B encouraged the company’s decision to make 2013-2014 ‘A Season of Eric.’ It was only the second time in the company’s history that an entire season would be dedicated exclusively to the works of a single playwright (five years earlier, the season was dedicated to Matthew Ivan Bennett’s plays).

THE SEASON OF ERIC

As The Utah Review introduced its retrospective of that season, the feature opened with Samuelsen own words: “So: the Season of Eric. And I’m Eric; apparently sufficiently known (or at least notorious) to warrant not just a season of my work, but a marketing campaign based on my first name. It’s immensely flattering and a tremendous honor. Obviously, the greatest five events in my life were when I married Annette, and when each of our four children were born. I’m not kidding when I say this: The Season of Eric comes sixth.”

The Season of Eric produced stunning contrasts. If one had been presented the scripts of the works produced that season without knowing who the playwright was, they would have been shocked to discover it was the work of a single individual. The Season of Eric stretched everyone’s capabilities to new heights. Samuelsen’s scripts always have been anything but easy for actors to come to terms with during rehearsals: the rhythms and pauses are complex as Samuelsen strives persistently for precision of language and memorization, therefore, is a challenge. The dramaturgy for a Samuelsen play necessitates a relatively immense compendium of interdisciplinary materials synthesized with the accounting of the playwright’s personal experiences.

Prior to the regular season, audiences received an early taste when Samuelsen saw his English translation of Ibsen’s Ghosts presented in a Script-in-Hand reading. Audiences zeroed in on the moments when Samuelsen made visible the inherent bits of wit in the play, which often have been lost in more traditional renderings of this classic.

Opening the regular season, Nothing Personal still ranks, at least for some audience members, as one of the most uncomfortable productions ever encountered on the Plan-B stage. While acts of torture were not visible, the references overwhelmed some observers. Samuelsen created a surreal masterpiece, piercing through the ethical and moral concerns of torture and the preservation of civil liberties. The play seems to start off on the factual civil liberties questions of Susan McDougal’s imprisonment during the Whitewater scandal of the 1990s but then morphs into a nightmarish scenario exemplifying how torture of the accused came to be an acceptable practice in a post-9/11 society. The scenes representing torture and sensory deprivation were suggested by the play’s sound design (by Cheryl Cluff, Plan-B’s managing director), including animal noises and screeches along with rattling chains and scraping metal. Susan is also shown in shackles.

“Samuelsen’s ability to make things personal is at its peak in this play,” Oppedisano wrote. “No longer are foreign prisoners of war in Guantanamo a news story; they are suddenly people standing before the audience in real flesh and blood.” She ties the thematic messages of humanism to spirituality in the work: “Whereas in most Mormon drama, and in the vast majority of Samuelsen’s other plays, characters struggle with their faith or struggle living out their faith, Kenneth and Susan have no such difficulties. Kenneth is entirely self-assured in his personal salvation through Jesus Christ, and Susan is almost dismissive of her similar professed acceptance of salvation and unconcerned with the particularities of any dogma.”

In the middle of the winter portion of the season was Clearing Bombs, which imagined a night-long discussion during World War II by economists John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich August Hayek. Samuelsen’s erudition always was a hallmark in his work but there were some reservations about whether he could successfully steer audiences toward the complicated terrain of economic theory. Genius as ever, he introduced an Everyman character who effectively gave the audience-friendly, hands-on perspective clarifying the jargon uttered by his two compatriots on the chapel rooftop. As recalled in 2014, “many audience members loved it and said how surprised they were at the emotionally involved production. They really thought the play helped to personalize the basic economic issues for them,” Rapier explained.

Closing out the Season of Eric was 3 – three short plays about Mormon women in various church ward settings, that served to be an apt season-ending valedictory for the playwright. As The Utah Review noted at the time, “What makes 3 remarkable is the quiet, almost intimate feel that is miles away from the emotionally riveting tone of Nothing Personal… Nevertheless, there is the same bottom-line question in both instances that is as silent as it is traumatic to confront: Is the price we pay individually and collectively worth it in our agenda for perfectionism? Exploring the question most certainly straddles the line of religion and theology but it also is one that many philosophers and pundits today avoid venturing into the territory. 3 asks all of us to reconsider where our moral, religious and ethical sensibilities lie. It is a call to rediscover humility and to find new appreciation for our natural gifts of human character.”

The Season of Eric also showcased Samuelsen’s appreciation for noirish humor. This came in Fairyana, an episode in the Radio Hour series, which was given its single-performance premiere in the 2013 holiday season and was aired live on KUER-FM’s RadioWest program. Conceived years before as a stage play, Samuelsen had written about a group of children’s television show writers who had the major dysfunctional traits and habits that would run antithetical to the Christmas spirit. However the original script did not have a specific holiday reference and Rapier suggested adding Christmas to it. The original Snoogums character became Santa’s favorite elf. “I mean, Fairyana‘s an exercise in extended irony–awful, damaged human beings writing a cheerful children’s show. Adding Christmas seems natural,” Samuelsen said in an interview with The Selective Echo. He added that Christmas was his favorite holiday.

For Samuelsen fans, it was a surprise to see his capacity for dark humor. He accomplished the neat trick of making the phrase “Snoogie oogums want yummy yum yums” memorably creepy. And, it was a holiday show with gunshots. (All Radio Hour episodes are archived and available at KUER’s RadioWest page.)

Samuelsen explained his interest in exploring dysfunctional holiday settings, citing his appreciation for the film Bad Santa and the television series The League, which aired on the FX cable network. “It’s about a group of guys who have a fantasy football league,” he explained. “They’re awful, awful human beings, and they’ll literally do anything to gain an advantage in playing fantasy football–like, two of them are attorneys, and they include a football trade in a plea bargain agreement (very much to the detriment of the client). Anyway, a lot of episodes of The League take place during holidays–Thanksgiving, Halloween, and, of course, Christmas, where Taco (easily the worst person among the characters) causes a ruckus at a local mall’s Santa village by insisting that Santa’s dark counterpart, Kegel the Elf, be given equal time.”

THE KREUTZER SONATA AND THE ICE FRONT

As outstanding as The Season of Eric was, Samuelsen gave Plan-B some of its most incredible blockbuster moments in The Kreutzer Sonata (2015) and The Ice Front (2017).

Borderlands shined when Plan-B celebrated its 20th anniversary. Opening the company’s silver anniversary season, The Kreutzer Sonata was a creative declaration of excellence. Directed by Rapier, it was one of the most thrilling pieces of chamber theater that could be presented in less than 50 minutes. Samuelsen’s play transformed Leo Tolstoy’s novella of the same name – a story about a man going mad who tries to rationalize murdering his wife, believing that she was having an affair with her musician friend. In collaboration with the NOVA Chamber Music Series, the play featured live excerpts from the Beethoven work of the same name, with pianist Jason Hardink and violinist Kathryn Eberle, the Utah Symphony’s associate concertmaster, performing.

Samuelsen captured the driving pace of Beethoven’s work in a theatrical setting that was stupendous at every turn. He let Pozdnyshev (performed brilliantly by actor Robert Scott Smith) explain the most candid depths of his madness while drawing the audience inward to “watch, learn and listen” in the way this tormented man might have heard the music. Only the first movement was played in its entirety and, in more than 15 other instances, Samuelsen weaved the music — sometimes no more than a bar or two of music or an extended yet brief segment of one of the sonata’s other two movements — progressively deeper into the monologue, often with Pozdnyshev speaking over the musicians’ phrases. As The Utah Review highlighted, this was music as classic mise en scène — the play’s de facto fourth character.

Samuelsen trimmed Tolstoy’s 32,000-word novella to just 3,500 words in the script: 70 percent were his own and the remaining portion came from the Russian novelist. He initially listened to a live performance of the entire work by Eberle and Hardink. As he pursued the project, he said, in classic Samuelsenesque style, “I listened to punk rock – The Clash, Sex Pistols, Ramones. It helped me get pretty close to where I wanted the play to be.” Eberle said the experience was so tremendous that future performances of the sonata would be approached with the play in mind.

In 2017, The Ice Front again raised the bar for Plan-B. It featured the largest cast ever (nine actors) and was among the longest plays in the company’s history. And, it sold out its entire production run more than a week before its scheduled opening.

It is a masterful synthesis of all of the most significant traces that encompassed Samuelsen’s work and his life. The Ice Front takes audiences back to Nazi-occupied Norway in 1943 and to the precise moral dilemma confronting the members of the Norwegian National Theatre in Oslo. The actors contemplate the prospects of sabotaging a production in which they would have to submit as performers and agents of propaganda.

In one scene, Peter (played by Daniel Beecher), a character who normally plays leading man roles, says, “We could act badly on purpose. We could sabotage the play, and limit its propaganda value to the degree that we can. That’s risky, very dangerous. We very well could be killed. But it remains a possibility.” Still trying to sort out why the authorities insist on making the play happen, Birgit (performed by Stephanie Howell) worries about becoming a “victim of circumstance,” adding, “I don’t want events to control us; I’m a stage manager. We want to make things happen.” Eventually, the actors vote 4-1 in proceeding but by following the tenth and most consequential commandment of the Resistance: “If you absolutely must work for Germans or quislings, you will work badly.”

The idea of writing the play that became The Ice Front was more than 30 years in the making, based on research he discovered as he wrote his dissertation. However, Samuelsen had become fully absorbed with his life as a playwright, scholar and university professor so the project always lingered in the background. But, his father, Roy Samuelsen, who died in 2017 and to whom The Ice Front is dedicated, never gave up on encouraging his son to bring this play forward to completion and production. Samuelsen’s grandfather knew first-hand the moral significance and strategic value of The Ice Front rules and the brave risks many took, acknowledging that Resistance was the only morally correct thing to do. His uncle was a war hero who received among the highest honors of the Norwegian military. But, some of those courageous men and women involved in the Resistance paid a deep price in terms of their physiological and cognitive well-being, as anger, alcoholism and untreated Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder would disrupt and consume their lives long after the war ended.

Samuelsen was at the height of his intellectual and creative powers, even as his body struggled to cope with numerous health crises and long hospitalizations. The humanistic challenges in The Ice Front are as formidable, incisive and existential as they were in Nothing Personal. However, the 2017 audience also was better prepared emotionally than the 2013 audience to heed the warning signs of history – the virulent expressions of intolerance, hatred, discrimination and bigotry that currently cause great distress in our nation.

As previously highlighted at The Utah Review, Samuelsen deftly excavated stories about ordinary individuals – the actors and professionals in a national theater in Oslo, for example – who variously fall along points on the spectrum between the protagonist victim and the antagonist villain. Again, as Birgit mentions, “I don’t like this, being a victim of circumstance.” In The Ice Front, Birgit and the other characters vividly demonstrate what it must have been like for ordinary Norwegians to endure that period of history. Late in the play, they begin to comprehend the dynamics of history’s critical judgment and the hope that they will be forgiven. The contemporary parallels are unmistakable. The formula for Samuelsen drama’s contemporary relevance always will be urgent, wise, sensitive, intelligent and spiritual.

THE SUSTAINING OF A LEGACY

Samuelsen’s legacy is and will be multidimensional. His humility and gentleness were strategic strengths, certainly as they have encouraged and fostered a dynamic new literary generation of Utah playwrights and who have had their own work produced by Plan-B. The creative DNA of moral courage that propelled his work has replicated, multiplied and diversified, thanks to Samuelsen’s expert mentoring and teaching. The stream of new work is impressive in setting up more frontier territory in the Utah Enlightenment.

They include Melissa Leilani Larson, whose living room drama Pilot Program revolves around a professional middle-aged Mormon couple with no children who have been called to participate in an LDS program restoring polygamy. However, Larson sets her sights on a vaster landscape revealing the most insecure, humbling blocks in our paths of finding a self-actualizing state of consciousness in individual identity, faith and relationships. Matthew Greene’s Good Standing achieves a singular incisiveness about the church to which he once belonged and to his own lifelong contemplation about self-respect and conscience. A solo show from 2018 with one actor taking on 16 roles including the young man being excommunicated along with the members of the Mormon church’s high council and stake presidency, Good Standing also was one of three Plan-B shows within five years to be performed at New York City’s United Solo Festival. Three years earlier, similar honors went to Samuelsen’s The Kreutzer Sonata. Likewise, Morag Shepherd’s Do You Want to See Me Naked?, a Sackerson Theatre production, also was performed last year at the United Solo Festival. Shepherd, who has had two plays produced by Plan-B, also is one of the producing directors for Sackerson’s A Brief Waltz in a Little Room: 23 Short Plays about Walter Eyer. Presented as a unique, intimate one-on-one immersive experience, the play arises from the life experiences of a fictional forty-something Mormon man of familiar circumstances and conventional means but also who is embroiled in his own identity crisis.

Samuelsen thought constantly about the limitations, challenges and aspirations for a Mormon arts and letters community and how a play, book, film or other creative form translates to and transcends audiences who look to the work for its humanist and spiritual perspectives and entertainment potential, especially if they are neither Mormon nor from Utah. With such a penetrating interest in everything from politics and culture to sports and history, he contextualized these concerns in compelling ways. Take, for example, the film comedy Napoleon Dynamite, with its strong local and regional roots. As highlighted at The Utah Review in a feature about the film’s 15th anniversary, Samuelsen earlier characterized Napoleon Dynamite as “the one genuine crossover hit of the entire Mormon film movement.” Noting that it was made by a Mormon film director, starred a Mormon actor and its story echoes life in a mainly Mormon community, Samuelsen explained that “its outlook and approach are more directly informed by a thoughtful examination of Mormon culture than even the HaleStorm comedies.”

Samuelsen put its well: “For an independent film to succeed, the film itself has to be the star. Audience members have to be attracted to that film, usually because they have heard about it, heard that it is offbeat, unusual, that its story is not structured the way most traditional Hollywood narratives are structured, or because it is amusing or provocative in ways standard Hollywood films often are not. This is precisely the case with Napoleon Dynamite.” And, as he notes, when Fox Searchlight, the distributor, advertised the film, it highlighted those elements.

Samuelsen’s comments translate precisely to why the creative bond with Plan-B Theatre worked so well. His plays rightly were the stars of their respective productions. Oppedisano wrote that “in finding artistic common ground, the playwright and the production company have created one of the best examples of theatrical partnership the state has seen. And while their approach to activism may not bring about a revolution, it makes for good drama—Mormon or otherwise.” However, four years after Oppedisano’s well-chosen words were published, it is apparent that, indeed, a revolution is underway, as evidenced by the works being created by his former students.

The paragon of patience, integrity and selfless dedication, Samuelsen persevered, produced a body of plays that will grow steadily in its cultural significance in the forthcoming decades, wisely guided talent to believe in their authentic worth and merit of expression and lit a flame that is inextinguishable in the Utah Enlightenment.

NOTE: For obituary and information about services, see here. In lieu of flowers, Samuelsen requested that donations be made to Plan-B.