But I grew up in a landscape large enough to hold what I felt when the world of people pushed me away. There, where badgers roamed, where herons speared small fish in shallow pools, I found my place. I took my sketch pad and tackle box to the banks of that small creek and washed myself in the rivulets of sound—of beaver tail slapping against the water, the screech of redtail hawks, the snap of branches from deer, the coyote’s call. That was—is—my home, where I drew the landscapes I loved—and draw upon them still—to make the world as it could be. — Taylor Brorby, excerpt from text for A Boy Like Me (2024) for voice and chamber orchestra, composed by Chris Myers.

This year’s selections in The Utah Review for the top ten moments of the Utah Enlightenment in 2024, the tenth annual edition, stood out for their spiritual and emotional impacts. In Utah, there are creative producers in the arts who are genuinely elevating the contemporary experience – with the sum of its tensions, problems, conflicts, disappointments and crises – to an enthralling sensation of healing, revelation, atonement and empowerment. They also represent new directions which always are worth the efforts in taking risks. Unquestionably, the call to spiritual intelligence will be greater and more urgent in 2025, if we are to rise above the disturbing and disheartening dynamics of our current sociopolitical landscape.

THE UTAH REVIEW’S TOP MOMENT OF THE UTAH ENLIGHTENMENT IN 2024

Many film festivals augment their programming with non-film events and activities but few can claim the distinction that this year’s Utah Queer Film Festival (UQFF), presented by the Utah Film Center, achieved with a concert featuring four world premieres by Utah-based composers. It was a bold programming stroke but one that festival director Russell Roots and its programming committee, led by Cat Palmer, believed fit tightly into the ideal of a film festival as a safe, comfortable home space for the community.

Recognized as the top moment of the Utah Enlightenment in 2024, the brainchild of Chris Myers, Life After Laramie: A Matthew Shepard Memorial Concert, comprised an exceptional quartet of short works contemplating the themes about where queer people find home and how place defines their community. Each composer put their unique imprint on the themes — Myers, Miranda Livengood, Garrett Medlock and Jared Oaks — drawing from a palette of styles, forms, moods, emotions, instrumentation and source materials as diverse and expansive in representation as the community itself. Performers included musicians from the Ballet West Orchestra, NOVA Chamber Music Series, Utopia Early Music and the Utah Symphony.

Medlock was the vocal soloist for his composition, If You Use Your Senses: Meditations, a startling but effective take on a form riffing off the Christian church’s Stations of the Cross. Scored for bassoon (performed by Medlock’s husband, Dylan Neff) and piano (Nicholas Maughan), Medlock sang the text he composed for the cycle — Sound, Sight, Smell, Stabat, Taste, Touch, Senseless, Sleep — that transported listeners to the fateful location in Laramie where Shepard was tortured. Each scene profoundly makes palpable the psychological, emotional and spiritual suffering that Shepard endured before his death. The instrumental parts rounded out the text, marking the natural characteristics of the landscape, even Shepard’s mother who lapses into grief and, in the case of the piano, serving as the omniscient narrator.

Bleeding, which Oaks (musical director for Ballet West) composed in memory of a beloved friend (Steve Finau) was a perfect companion piece to Medlock’s meditation. With finely woven textures taken from styles set apart by centuries, Oaks fused an Elizabethan Era madrigal (Weep, Weep, Mine Eyes by John Wilbye) with a deft command of serialism, in a work featuring a poetic text by May Swenson (1913-1989), a Utah literary figure. Its premiere featured vocalist Yvette Gilgen and Lisa Chaufty on recorder.

Using texts by C.E. Janecek, Miranda Livengood’s Catching Venus comprised a triptych of songs — Satellite Dogs, Constellation Lovers and Voyager — with the composer on guitar, Janecek on percussion and Polly Redd as singer. The songs, rich in cosmological sentiments, served as a bridge to holding onto hope and optimism even amidst current events that emphasize affirmation and acceptance have yet to be permanently guaranteed.

It was Myers’ A Boy Like Me, the stirring composition that concluded the concert, which brought the audience to its feet. Sweeping in its natural synergy of musical and literary language, the piece featured a superb text by author Taylor Brorby (Boys and Oil), which was sung by Medlock, who was dressed in a plaid flannel shirt just like what Shepard would have worn. Myers embedded the community’s hardscrabble experiences and its immense sacrifices in a majestic reflection of what connects every sector and quarter of the queer community and the overarching belief in social justice so that everybody can safely and comfortably find the place they surely can call home. An ambitious undertaking as large as its creative thematic expression, this premiere of A Boy Like Me epitomized the breadth and depth of a supportive community of musicians, which included the three other composers from the concert as well as performers from the aforementioned groups.

THE REMAINING LIST OF TOP 10 MOMENTS FOR 2024

Presented in no particular order, the following nine moments round out the list of Top 10 moments of the Utah Enlightenment in 2024:

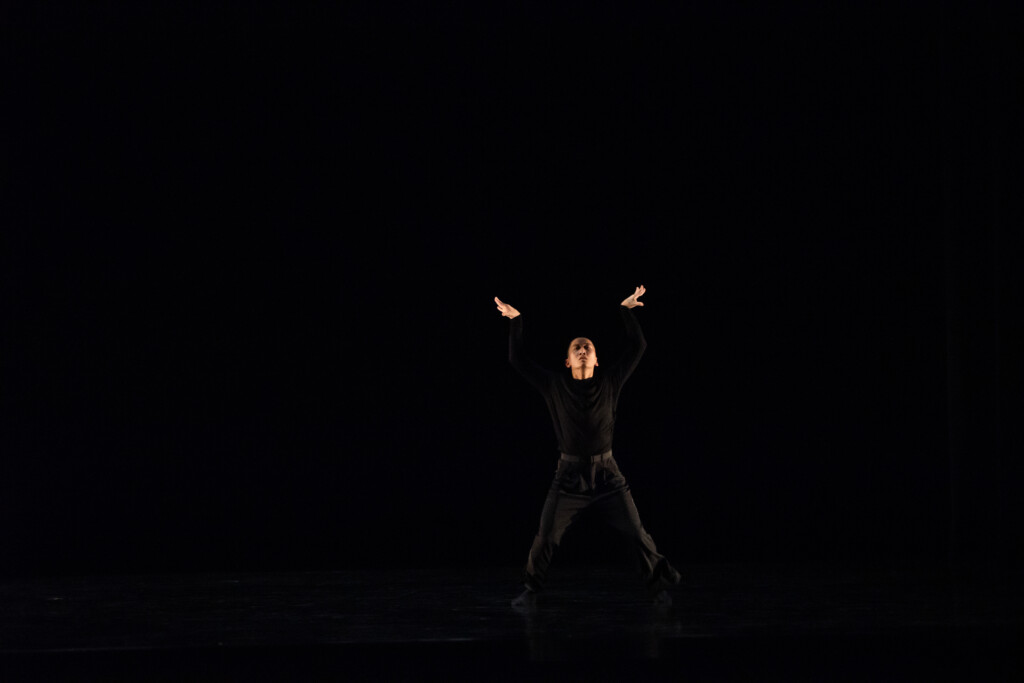

This was an epic year in dance, which continues its reign as empress of the performing arts in Utah. There were many high points but several reached toward the heavens. In the final moments of its Gamut production to close out the 58th season last spring, Repertory Dance Theatre (RDT) achieved one of the most spine-tingling sensations in the world premiere of the Solfège, which was Yusha-Marie Sorzano’s first commission for the company.

It is dance theater par excellence and Sorzano is a choreographer with an extraordinary intuitive grasp of the music she selected. In this case, it is Tan Dun’s 2011 Symphonic Poem of Three Notes. While the score certainly stands on its own merit for listening, Sorzano extends its emotional capacity, precisely in line with choreographed movement. Solfège telegraphs our fascination with the cycles of the natural world, which are intertwined with sirens and otherworldly figures, which are reminiscent of the characters in Guillermo del Toro’s film Pan’s Labyrinth. The company also performed Sorzano’s work during its East Coast tour this past fall, which included the Whitney Museum of American Art, in conjunction with the museum’s Edges of Ailey installation.

The dancers gave Sorzano’s choreography its full cinematic effect, performing in a natural-fantasy world, starting from its primordial roots and building to its greatest burst of drama and cacophony of industry and finally returning to its primordial home. And, then there was the final moment: soloist Jon Kim, who left the company after five years to pursue new artistic ventures (including UNA, a San Francisco-based dance company). Kim returned us to the primordial roots which opened Solfège. Even without the unique circumstances that this was Kim’s final performance on the RDT stage, it was a stunning moment. This was as fine a dramatic ending as anyone could have imagined: Kim, standing as the lights darken; his presence reminding us of the selfless dedication along with the compassion and conscientious sensitivity he has shared with his peers and with the dance community during his tenure. Its significance resonated with the absorbing narrative Sorzano crafted.

Not to be outdone, Ballet West is at the heights of its artistic powers. In 2017, when Ballet West launched its choreographic festival, Adam Sklute, artistic director, told Dance Magazine, “We want this festival for choreography to do what the Sundance Film Festival does for film—create a hub for creativity in dance.” From June of this year, judging by the exceptionally enthusiastic response from the opening night audience, Choreographic Festival VI: Asian Voices clinched the gold standard for artistic innovation, with marvelous works by four internationally known choreographers performed by Ballet West and the Columbus, Ohio-based BalletMet.

Exhilarating and inventive at every turn, Asian Voices was multidimensional in exploring choreographic storytelling through uplifting themes of nostalgia, the liberating energy of youth, migration, universal journeys of love and relationships and the certainty of historical and natural time cycles. Two world premieres by Asian female choreographers and two Utah premieres by Asian male choreographers electrified the stage at the Jeanné Wagner Theatre in the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts.

Capping an outstanding 60th anniversary season for Ballet West, the stupendous Asian Voices production sizzled with the precise cinematic-like emotional energy that makes such festivals a must-attend destination for dedicated arts audiences of all intellectual and demographic stripes. In each work, as noted in a preview published at The Utah Review, Asian artists effectively drew on techniques that have been practiced for centuries while they also incorporated their own interconnected sense of identity, to forge their creative futures that are ingenious and resonate with the foundations of their own heritage. The works featured were: Caili Quan’s Play on Impulse (world premiere), Phil Chan’s Amber Waves (Utah premiere), Zhong-Jing Fang’s Somewhere in Time (world premiere), and Edwaard Liang’s Seasons (Utah premiere).

Likewise, Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company has been a dynamo of impressive creative powers. Last winter, in the middle of Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company’s 60th anniversary season, Traverse was a perfect Homecoming production, highlighting six new works and a company premiere, which exemplified the tremendous artistic culture that has defined the company.

With works by two alumni company members and the six current dancers, the creative principles which the founders Shirley Ririe and the late Joan Woodbury set forth resonated and echoed throughout the evening. There were works of astute sociocultural significance, pieces reflecting the ardor and rise and fall of emotions expended in the creative process, intimate choreographic statements about individual personalities and audience-pleasing displays of play and whimsy. The production, which featured guest performers including students from The University of Utah School of Dance, was dedicated to Woodbury, who died in 2024 at the age of 96.

One of the best examples befitting Traverse’s creative brief, the closing piece was a hoot for the audience — a rollicking glimpse at how a sports novice can find sassy fabulousness even in a plain old game of pickleball. Inspired by never having played any sports, Alexander Pham (a former Ririe-Woodbury dancer who is now in his first season with RDT) decided to set Perfect Match as “a whimsical reimagining of that missed experience.” The work, which was performed by Pham with Severin Sargent-Catterton, hit on every cylinder. As entertaining and witty as it was, Perfect Match was also an artistically demanding and challenging piece of choreography. It pulled in movement from several dance languages and vocabulary, including ballet, contemporary dance and pop moves. The collage explored in the three movements matched up beautifully with musical selections including Bohoman’s Elevator Music and bad guy, performed by Billie Eilish and written and produced by Finneas O’Connell.

NOVA Chamber Music Series’ Dance in the Desert concert (March 10) was perhaps the season’s most challenging for the musicians but the set of five magnificently performed works, which included a world premiere, also was among the most easily accessible for the audience.

For the concert finale, the world premiere of Laura Kaminsky’s Desert Portal was a delightful celebration. As a multimedia piece of dance theater, every component fit perfectly and clearly marked the natural transitions during a day in the desert — from the six musicians to the visual projections of work by internationally renowned artist Rebecca Allan and to the quartet of dancers.

As noted in the preview at The Utah Review, Kaminsky composed the piece for the planned 2020 inaugural of Arizona State University’s desert humanities initiative but it was scrapped when the pandemic shut down all in-person events. The work was set to be performed as a procession with desert rocks being carried by audience members, which would be signaled and led by a drummer. Dancers and musicians would walk in rhythm to their places, and would encircle the audience members, while projections of art images by Allen would provide the visual entertainment before the event began.

For its Salt Lake City premiere, Desert Portal, which was conducted by Gabriel Gordon, took on a new form that can easily be replicated in future performances. The one suggested note is that much of the opening professional ‘vamp’ can be cut. The seven musicians processed and were spread across the stage, with the two percussionists flanking them at each end. This arrangement worked beautifully, as the dancers processed into the performing space and then moved, slithered, twirled and crawled on stage. The three dancers (Sarah Lorraine, Fiona Gitlin and Tawna Waters), along with Myriad Dance Company’s Kendall Fischer, who also performed and led the collaborative choreographic efforts, did a fabulous job on capturing every transition throughout the day, from predawn to a brief storm and to midday heat and the brightest sun and finally to twilight and nightfall.

Likewise, the musicians (which included Lisa Byrnes and Mercedes Smith, flute; Katie Porter, clarinet; Sam Elliott, trombone and Walter Haman, cello) were equally cohesive, cogent and explicit in transmitting the imagery of Kaminsky’s music and Allan’s art through sound. And, kudos to the smart, infectious vamps from both percussionists (Keith Carrick, and Eric Hopkins) at the beginning. Every component gelled with the theatrics in this compact piece, including the lighting design by Logan Bingham that enhanced Desert Portal’s easy accessibility for audience members.

Plan-B Theatre continues to be the paragon of a performing arts organization that fulfills the objective of the task surrounding ‘representation matters’ and how that is accomplished through quality work that is timely, elucidating and timeless. At the opening of Full Color, Plan-B Theatre’s 34th season opener, the setting was pleasant and inviting: eight people enjoying each other’s company and feeling comfortable at home, outside a tent in nature. As each person shared a story, the production’s epiphany expanded organically, one narrative at a time. While the audience was welcomed to listen, the expectations for us in this ingeniously curated theatrical experience meant resisting the comfort of being passive or colorblind and acknowledging contemporary realities of systemic biases, discrimination and racism. In plain words, “One cannot fight what one does not see.”

Full Color popped with heart, wit, poetry, intellectual depth and soul-bearing emotion. It was the third in the company’s Color Series Productions featuring work by members of Plan-B’s Theatre Artists of Color Writing Workshop. As noted in The Utah Review preview, the production comprised short first-person monologues by eight BIPOC playwrights who reflect on their experiences in Utah. However, instead of the playwrights performing the monologues they have written, the performances were entrusted to their own doppelgänger — actors who relate, identify and can sincerely testify to the gist of the experiences and the stories the playwrights put into their script. The short monologues were written by: Dee-Dee Darby-Duffin (Fried Chicken), Courtney Dilmore (Here), Tito Livas (Let’s Not), Tatiana Christian (I Still Have To Live Here), Darryl Stamp (American Survival Story), Iris Salazar (Life Is Color), Chris Curlett (Fox and the Mormons) and Bijan J. Hosseini (At Least One).

The actors excelled in their creative task, who compelled us to realize that if we do not see color in its fullness, we also fail to see how racism and discrimination continue in our neighborhoods, our schools and in our own lives. Each story stood on its own merit for its narrative impact but what made Full Color especially good were the finely woven threads that tied the entire package of eight amonologues together. This was not just a compilation of eight anecdotes but a comprehensive, multilayered testimony to how widespread and far reaching the experiences of BIPOC Utahns occur in virtually every domain. The order of performance sharpened the connections among the eight monologues, particularly in the latter half of offerings that reinforced the point that such experiences are not anomalous or singular by any measure.

Westminster University’s concert series has become well known for bringing performers and programs that increasingly reflect the expanding ethnic diversity of Utah’s rapidly growing population. Last March, Alam Khan, the internationally distinguished master of the sarod, a 25-string instrument with no frets which comprises strings for performing melodies as well as sympathetic strings to create resonating drone-like sounds, came to Salt Lake City for a residency which included the India Cultural Center of Utah, in partnership with the Mundi Project, and which culminated in a concert as part of the Westminster Concert Series (WCS). For the Westminster concert, Khan was joined by Indranil Mallick, who performed on tabla, in a brilliant display of North Indian classical (hindustani sangit) raga, which highlighted the intense emotional capacities in the music. The spectrum encompassed slow, meditative and introspective unfolding of the raga that segued into virtuosic elements propelled along by melodic phrasing and rhythmic sentences, including Khan cross picking the resonating and Chikari strings of the sarod. The evening’s music grew originally, moving from broad improvisations to well-defined interacting sections between melody and rhythm and ultimately back to a spell-binding improvised conversation between the two musicians. Overall, it belongs on the prime list of the year’s most edifying musical experiences in the Salt Lake City performing arts scene.

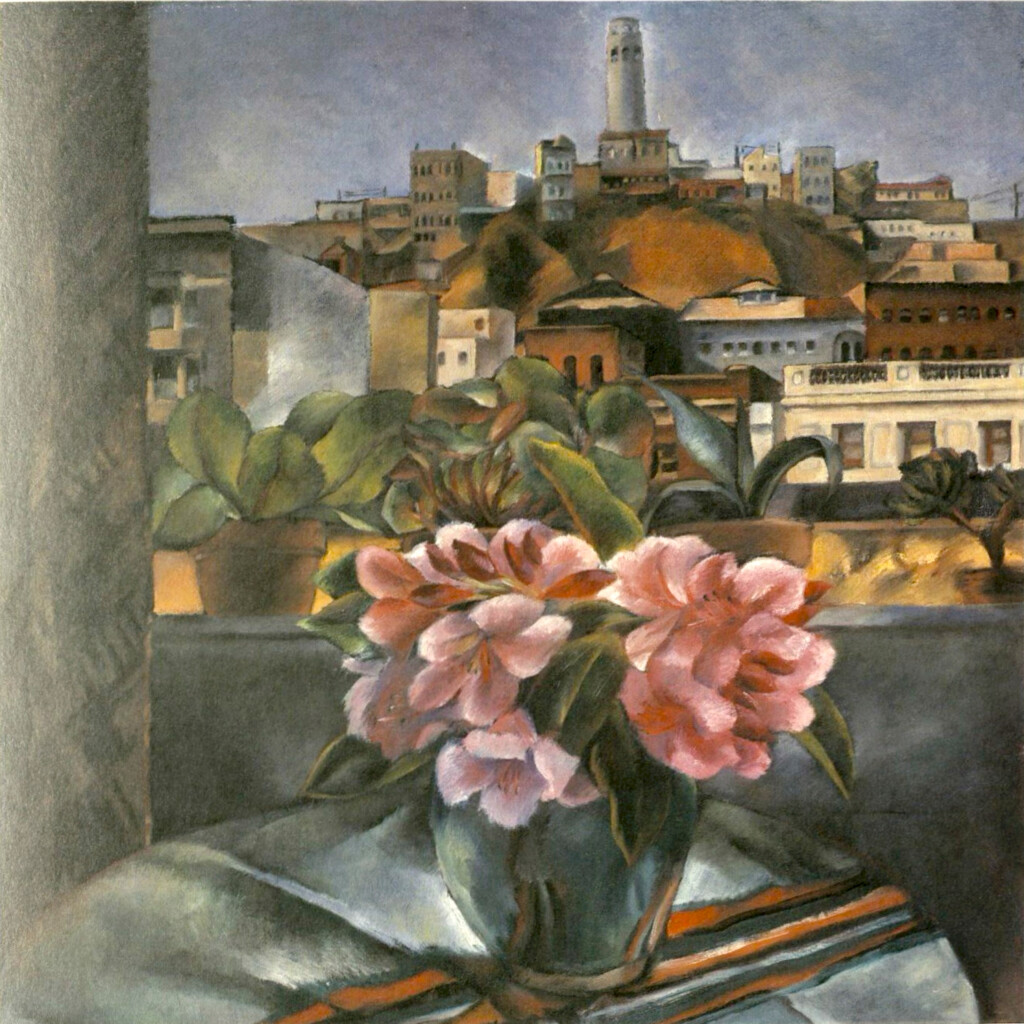

Recent exhibitions at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) have not only been spectacular but also significant in encouraging viewers to examine art history in a new perspective. Last spring, the Utah Museum of Fine Art (UMFA)’s Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo was a brilliant masterpiece on its merits, impressively commanding visitors to think anew about American modernism in the 20th century. With more than 100 works, including many that had never been publicly displayed before, the exhibition highlighted these artists, who were among the most active and visible female artists of Japanese descent, born in the generations before World War II. A separate smaller exhibition but just as powerful in its representation, Chiura Obata: Layer by Layer documented the creation and conservation of the artist’s Horses screen (1932), one of the greatest 20th century works celebrating an iconic image of the American West.

Collectively, Hayakawa, Hibi and Okubo, each prolific in their respective regard, represented more than 80 years of active creation. Their lives encompassed a time of anti-immigration laws when Asian American immigrants were prevented from becoming naturalized citizens as well as the events of World War II that disrupted their lives and led to American citizens and immigrants of Japanese descent being interned in camps, including in Utah. Incidentally, Hibi and Okubo were imprisoned in Topaz, Utah, from 1942 until near the end of the war, as was Obata. Along with the concurrent Obata room show, Pictures of Belonging was yet another milestone for UMFA, which has played a major role in recent years emphasizing how these four Japanese American artists, along with their colleagues, carved a prominent presence as among the greatest figures of American modernism in the 20th century.

In recent years, Utah’s arts community has created work inspired by the focus on rehabilitating and saving the Great Salt Lake. Last spring, the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) presented As The Lake Fades, an outstanding exhibition exemplifying cross-disciplinary approaches uniting science and the humanities.

In one social media post, Darren Parry, a local Shoshone Tribe leader, wrote, “Saving the Great Salt Lake is not a science problem, but a values problem.” This sentiment was evident, as the 15 artists in the exhibition As the Lake Fades collectively built a compelling platform for sparking substantive cross-disciplinary conversations we should be having that connect scientists with their counterparts working in the humanities. The artwork girded the descriptive theme of the Great Salt Lake as our “nonhuman kinfolk,” which Parry recalled how his grandmother referred to it. While the exhibition was large in scope and presentation, its understated manner fed a constructive, welcoming atmosphere that could help transcend partisan stubbornness, political identity and, hopefully, a good chunk of the recalcitrance we use in balking at our responsibilities as stewards of nature.

The exhibition was part of certainly the largest in breadth and depth exploration of Utah natural environmental issues of recent years, as it was complemented simultaneously by equally compelling exhibitions at UMOCA. Just as prominent in its cross-disciplinary approach as the artists engaged with As The Lake Fades, photographer Diane Tuft’s Entropy was stunning for its vivid colors but also alarming for its documentation of the climate-related stresses on the Great Salt Lake. The artwork documented the impacts through saturated colors, visible cracks, and clear textures. The photographs were taken in 2022 and images were magnified in their significance when viewed along with the video installations in the As The Lake Fades exhibition. Entropy reinforced the consensus that both scientists and their creative counterparts in arts and humanities have cultivated about the dire state of the Great Salt Lake. Yet another outstanding example of cross-disciplinary expression exhibited in UMOCA at the same time was The Biocrust Project by Jorge Rojas and Dr. Sasha Reed. As the inaugural Canyonlands Research Center’s Artist in Residency project, courtesy of The Nature Conservancy, Rojas and Reed offered an immersive audiovisual installation and a centerpiece — a beautifully constructed scene of the biocrust, commonly referred to as the desert’s skin.

Rojas, a Utah multidisciplinary artist whose work is internationally recognized, wss the center’s first artist in residence. He connected to Reed, a U.S. Geological Survey researcher, who has been studying the biological significance of the biocrust and has been augmenting her work with contributions from Indigenous knowledge. The CRC program, based at the Dugout Ranch near Moab (which The Nature Conservancy owns), is dedicated to cross-disciplinary perspectives joining artists and scientists. In a 2023 interview with the Moab Sun News, Rojas explained, “When people think about sustainability, people usually think about the Amazon, or glaciers.” He added, “But [biocrust] is the living skin of the Earth.” As for collaborating with Rojas, “Art and science are two sides of the same coin,” Reed told the Moab Sun News. “Both are about communicating things about the world to each other.”

Finally, when it comes to the founding of Utah’s tremendous art movement, its own “this is the place” moment occurred not in Salt Lake City nor Provo, Spanish Fork or Payson but instead in Springville, just about the same time as the town was being established in the 1850s.

As Vern Swanson, retired director of the Springville Museum of Art, noted in a written history, “The first intimations of an Art Movement came in 1848, two years before Springville was founded. While still in Winter Quarters, Nebraska, pioneer artist Philo Dibble (1806-1895), an early Springville settler, envisioned ‘the creation of a fine arts museum or gallery to be established for the benefit of the Mormon people.’” Dibble moved to Springville in 1858. “Through his panoramic painting of religious and historical subjects, his exhibitions of art and death masks of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, as well as magic-lantern slide presentations of famous paintings,” Swanson explained, “Dibble created a climate of interest for the visual fine arts in Springville within eight years of the founding of the City.” Swanson related a story from one of Dibble’s relatives: “According to a grand-niece, once during his rounds through town, Dibble plunged his sacred ‘Cane of the Martyrdom’ into the ground at the corner of First East and Fourth South and said, ‘The school gallery shall be here.’”

In the opening of the splendid short documentary film, Spirit of the Art City, produced by The Plains studio, Swanson mentioned Dibble as the spark that led eventually to the occasion of this year’s historical undertaking. The Springville Museum of Art marks the milestone with a major exhibition, Salon 100: A Retrospective of 100 Spring Salons and the Students that Built Art City.

The show opened simultaneously in late April, along with this past spring’s 100th annual salon, and the Salon 100 exhibition will continue through June 2025. The show comprehensively lays out the 100 years of the history of the salon in an organized and lucid fashion, especially in showing how the artworks selected for the salon have evolved in medium technique, style, aesthetics, subject treatment and other elements through every decade.

As Utah’s first art museum, Springville’s initial collection grew as local high school students purchased paintings and sculpture through an ‘Art Queen’ festival. Each student paid a penny to vote and the student with the most votes was named queen, with the funds used to purchase art for the museum. High school students led efforts to put on a Parisian-style salon exhibition, beginning in 1922 and which has continued annually each spring (with the exception of two years during World War II). As noted in the documentary short film, which is directed by Jared Jakins and H.B. Phillips, the museum now has “2,646 works of art and counting.”

Running a bit under 17 minutes, the film is fascinating in celebrating perhaps the Utah Enlightenment’s longest running enterprise of artistic excellence, which also put the state at the forefront as an art education pioneer, ahead of virtually every other state in the U.S. by similar measure. For example, the Springville museum has been instrumental in organizing the Utah All-State High School Art Show annually since 1971, which is coordinated in conjunction with the Utah Division of Arts and Museums. It is among the nation’s largest and longest-running student art shows of its kind.