The five dancers who will perform Dust. Breath. Place., a new work by choreographer Efren Corado, have transported themselves to a different world in the rehearsals leading up to the forthcoming premiere in three performances (May 2-4), as part of Repertory Dance Theatre’s Link Series (RDT).

Observing Easter morning rehearsal was spiritually uplifting. Eleven days before the premiere, it was evident that the dancers already had found the right emotional tone and the pace for Corado’s work, which encompasses the memories of his migration from Guatemala to Los Angeles in the 1990s as a boy. Corado could have taken any path to set this work: a solo piece which he performs or an ensemble of dancers who themselves have their own immigration experiences. While he selected five dancers whom he knows well personally and professionally, he also has set a creative process that epitomizes how dance becomes an exemplary vessel for solving a bigger problem. In this case: How do we listen to the stories of immigrants where words dissipate into human experiences that evoke empathy and advocacy in a natural moment of reflection and our capacity for humanizing interaction.

In an interview with The Utah Review after the rehearsal, the five dancers – Tyler Orcutt (RDT), Sarah Donohue (Utah Valley University) and Tiana Lovett, Austin Hardy and Natalie Border (SALT Dance Company) – spoke confidently about finding the most effective space for the work. Orcutt, who has been an RDT colleague during Corado’s entire six-year tenure with the company, says the process has evolved in two ways: listening directly to Corado’s story and them embodying what he and the other dancers understood. “In the broader experience, it becomes a hybrid,” he says.

Donohue adds that she doesn’t know a lot of stories about immigrant experiences and it was a bit of a surprise when she heard Corado talk about his memories. She explains that channeling her own role as a mother has been integral to the experience of creating Dust. Breath. Place. “I go to a visceral place which I automatically feel in my guts,” she explains. Border says that as Corado has given the dancers room for interpretation, they have “tapped into their own empathy” for making the artistic vessel for telling the story.

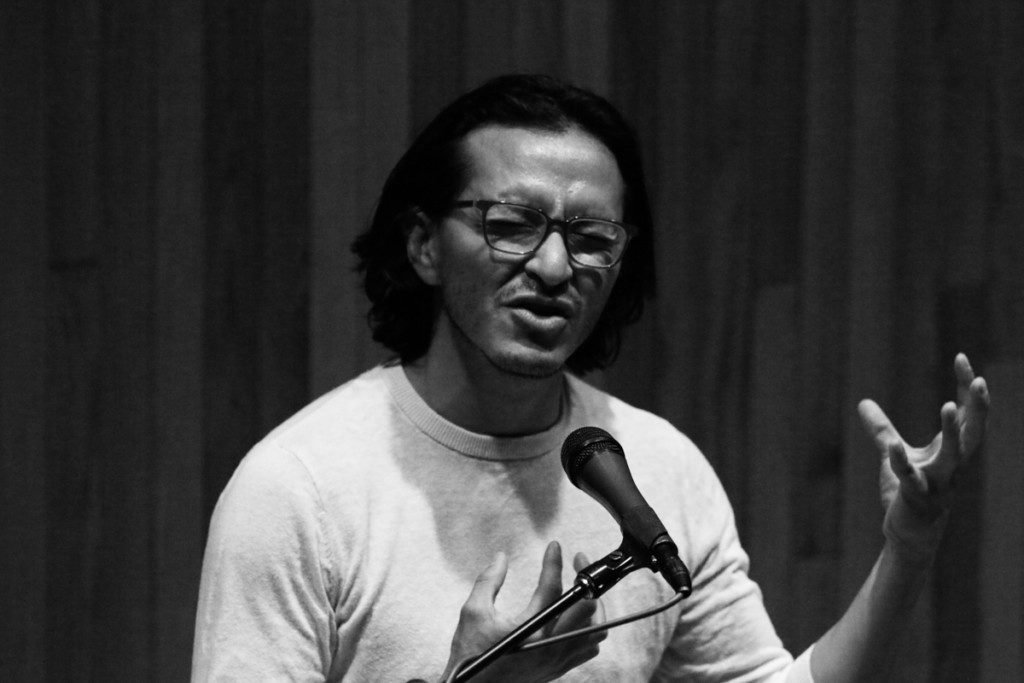

Corado, who speaks with the precision of language that communications his artistic intentions clearly to the benefit of the dancers with whom he works, has touched upon his story in various ways prior to this new work. In 2011, his master of fine arts degree thesis for The University of Utah’s School of Modern Dance was Writing love on my arm: finding the voice of consciousness in the creative process, which touched upon loneliness and how the choreographic process “helps develop a clearer depiction of experiences that have been sublimated in our nonconscious self.” He also shared the details of how he came to the U.S. at a 2016 event of The Bee, a popular local literary group modeled on other story telling venues such as public broadcasting gems The Moth Radio Hour.

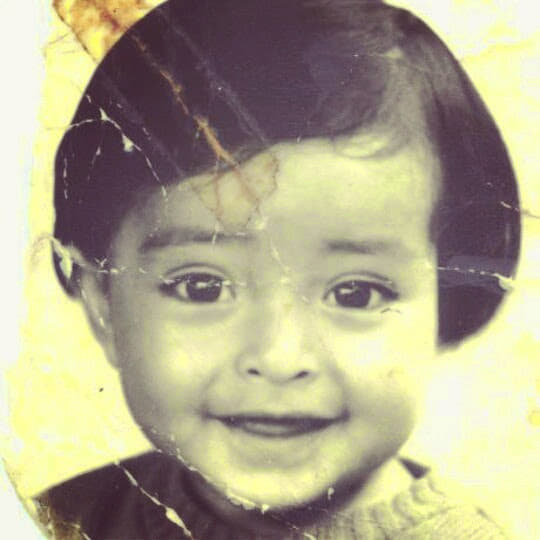

Born in 1983, he lived in a remote town comprising mud homes on the outskirts of volcano and where there was one faucet for running water in the town. The youngest child of three, Corado did not see his mother, who had gone to Los Angeles while he was still an infant, until he was 11. His journey to the U.S. was long and difficult, which began after his mother called him up to ask if he wanted to come to America. Arrangements had to be made for the young Corado to go to the home where a phone was available and the call scheduled.

A local coyote was recruited to transport Corado across the border. At The Bee event, Corado recalled the experience about going to a “complete stranger’s” house and his older brother warning the coyote that he would suffer the consequences if his younger sibling did not make the trip safely or was killed. Corado specifically describes the long seven-day bus ride from Guatemala and across Mexico, which he says required being in the bus eight or nine hours each day in the hottest, most humid weather. The discomfort was so bad that he went to the back of the bus, opened the window and vomited. In deadpan humor, he mentioned that when he saw how his vomit had splattered across the back of the bus, he said, “I was an artist before I knew was going to be.”

The tensest moments occurred at the border. Immigration enforcement authorities stopped the bus and pointed to everyone except Corado, which he said was a sign of fortunate destiny. The coyote instructed him to join a group of older men who were playing poker and he found a boy and a girl his age, which allowed for some playful moments.

Crossing the border became an adventurous game of sort. Because it was so hot, Corado was clad only in his underwear without anything to shelter him. He climbed on the shoulders of the men to carry him across the river, as a truck with immigration officers chased them along the river’s edge. Corado says it became a strangely fun game of being chased and once he had made it across safely, he got dressed and the coyote told him that they did not need to run any longer.

For the boy, the most amazing first sight in the new land was the carpeted room at a nondescript hotel where he stayed. Then, it was the first trip in a plane to Los Angeles. When he met his family, the first woman who approached him actually was his aunt, and he recalls crying, believing that the woman who had introduced herself as his mother really was that person. However, when his real mother stepped forward, he was skeptical and unsure about what was going to happen to him. When he graduated from high school in 2001, he was fully aware that as an immigrant he had nowhere to go until he finally became a legal resident and was able to go to college (Chapman University).

Corado identifies as a Guatemalan choreographer but as someone who has spent his entire formative years as a dance artist and choreographer in the U.S., he also has pursued learning about the music and folk dance roots of his homeland culture. These elements are subtly integrated into the new dance composition and his musical choices are exemplars of cosmopolitanism including Melao Boricua, Bia, Mary Lattimore and René Aubry.

The work reinforces the sentiments he expressed in the closing moments of his story-telling at The Bee. He is grateful for the universe that “has unfolded in front of me,” sometimes in unexpected ways but with no need to be questioned. Was he afraid? He responds, “How would I know? I was curious. I was a little lost.” Returning to that Easter morning rehearsal, one can appreciate the elegant aspirations of dance to create a hopeful, less stressful, even joyful community.

Performances will take place daily at 7:30 p.m. (May 2-4) in the Studio Theatre of the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. Tickets and more information are available here.

Donations from individuals and fiscal sponsorship from Atlas Peak along with RDT’s role as producer make Dust. Breath. Place. possible.