In explaining the unrelenting discipline of training, the Stoic philosopher Epictetus wrote, “Then when the contest comes on, you have to ‘dig in’ beside your opponent, and sometimes dislocate your wrist, sprain your ankle, swallow quantities of sand, sometimes take a scourging, and along with all that get beaten. After you have considered all these points, go on into the games, if you still wish to do so; otherwise you will be turning back like children.”

In the pursuit of becoming a philosopher, Epictetus writes, “consider first the nature of the business, and then learn your own natural ability.” He tells us that only when we look over the strains, aches, drawbacks, humility and humiliations and consider them carefully, we can then begin to secure “tranquility, freedom and calm.”

By following Dan Higgins on Facebook or other social media platforms, one could pick up rather quickly the dance artist’s resonance with classic Roman and Greek philosophers, including Marcus Aurelius, a Stoic who also was the last emperor of the Pax Romana.

The vibe of the ancient philosophers is a good starting point to comprehend Higgins’ journey in becoming a dance artist with Repertory Dance Theatre (RDT), a pioneering company in the modern dance world for the last 54 years. In tandem, he is emerging as a choreographer, who is setting his third evening-length work within the last three years. Unlike many dance artists who started learning and developing their craft in their pre-school years (sometimes as soon as the age of three), Higgins started at the age of 18, when he enrolled in the dance program at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. Athletics dominated his childhood and high school years in Terra Linda, California, a small suburban community in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Epictetus likely would have been proud of John Timothy, Higgins’ high school football coach. In an interview with The Utah Review, Timothy, who describes himself as a lover of the arts especially in his all-encompassing tastes for music, says, “to play football, one should contemplate life first, to be committed, trustworthy and dedicated, and to show empathy and compassion.” Timothy’s comments also hint at Higgins’ communication style as a choreographer, which becomes evident in observing the open rehearsals for his upcoming premiere Speak [to read more about this upcoming premiere, see The Utah Review feature here] and those for Higgins’ last major work In. Memory. Of.

“While Dan always was very intelligent and was very sure about himself on the team, he also was open to suggestions and took time to think them out,” Timothy recalls. “He encouraged discussing questions together with team members to solve a problem. He showed a lot of creativity even then. I could already see and understand why he would be drawn to dance, which seemed perfect. He was open to everything. I saw then how he could lead a team or any group.”

“Push the earth” was Timothy’s coaching mantra. “If they did something wrong or made mistakes, they would have to do push-ups. Push the earth was to fight against and push away to become better.” Gymnasts understand this. So do sprinters. Definitely, dancers do as well.

While dance during his college days in Laramie represented a new landscape for Higgins, the passion for the performing arts already had been instilled before his college freshman days. His siblings have careers based in the arts and creative expression. Sean, who went to the Yale University School of Drama, is in the Elm Shakespeare company in New Haven, Connecticut. Billy is involved with the Stella Adler Studio of Acting, and Mary is field instructor and production wizard at the Telluride Academy. In a high school production of Hamlet, there was the duel in the second scene of Act V, which occurs after Hamlet’s earlier attempt to apologize to Laertes for his insane behavior. Laertes refuses Hamlet’s move, selects the poisoned rapier and the two fight. Dan was Laertes and Sean was Hamlet. “The choreography was like boxing,” Higgins recalled. “It was realistic. We’ve always been competitive so this was like being able to test each other.”

As Lawrence Jackson, a former University of Wyoming faculty member who now is on the dance faculty at the University of Alabama, recalls, “Dan came into the program with no dance experience at all and he jumped into it with no training.” Jackson, who also was an athlete before switching to dance, understood where his new student had come from and watched Higgins closely.

Jackson customarily introduced his class with a quote from Socrates, as noted in Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of Eminent Philosophers: “Ηe knew nothing except just the fact of his ignorance.” Unquestionably, the utter humility of the quote did not faze the new dance student. “He was a sponge right from the freshman year and this continued until he graduated. Very intelligent,” Jackson says. “He was very inquisitive. He would ask questions that no else had the guts to ask.”

Higgins was sensitive about not bogging down the momentum in classes where other students had much more training and technical skill than he did. “In his first year, he always was open to corrections and constructive criticism and he blended in and I knew he would be fine,” Jackson recalls. “And, he had a lot of things to work on to reach the level of others but he was doing this very quickly. He was surrounded by students, some of whom had started dancing when they were three years old and already had 10 or even nearly 20 years of training.”

Jackson says that Higgins’ passion could not be quenched easily. “And, he was very humble. He absorbed everything not just in dance technique but also the history of dance and legendary choreographers. He would call or email to talk about a text or something I discussed in class,” Jackson adds.

One of the most challenging tasks for any dance artist or choreographer is to articulate what their work means or the creative intention or muse that frames it. “I try to ensure my students just don’t go on autopilot about this,” Jackson explains. Regarding Higgins, Jackson adds, “At first he didn’t have the dance vocabulary but once he learned it he also learned to think deeply about it.”

Observing Higgins’ progress, Jackson decided to set a solo for Higgins in a university production based on Carmina Burana, Carl Orff’s enormous choral and orchestral work. This made a huge impact for emboldening Higgins’ desire to pursue a professional career. There also was the Snowy Range Dance Festival. Later, there were the summer intensive classes with RDT in Laramie.

“When he did the summer intensive classes with RDT in Wyoming, I could see how excited he was,” Jackson recalls. Even then, Jackson believed that RDT potentially could be the right fit for Higgins. “At RDT, I could see how good it would be for his confidence to bud and blossom. RDT always has done wonders for how artists such as Dan learn to take ownership of who they are.”

Dance summer intensive courses provide n excellent platform to gauge emerging artists. Higgins’ willingness to persevere and work hard caught the attention of RDT’s staff, including Linda C. Smith, co-founder and current executive and artistic director, and Nick Cendese, RDT’s artistic associate. In its dual repertory mission of sustaining and performing the historic canon of modern dance compositions and creating new work, RDT introduces its dancers to a broad, deep spectrum of movement languages and technical skills on multiple platforms. As Cendese explains, three criteria define the challenges for new dancers: “Don’t be afraid to work hard. You have to be comfortable by starting at the bottom. And, you must always seek out opportunity. Most dancers do well with one or two of the criteria but not all three.”

Smith remembers when she saw Higgins for the first time at the Snowy Range Dance Festival. “He was very green, wet behind the ears, and did not have a lot of technique,” she says. Sharee Lane, a choreographer who also was on the University of Wyoming faculty, learned about him through a colleague. “He didn’t dance in any of my pieces that I choreographed,” Lane adds.

Before committing to a full contract, RDT decided on a trial run with Higgins, which meant he was not compensated at the outset. “When I look at prospective dance artists for RDT, I am looking for soul. All dancers at RDT also are expected to choreograph work. For Dan, I knew this would be a new experience,” Smith says.

Her instincts suggested that while he might not have been ready technically, there was something about him that merited a closer look. Not all dancers, even those that are undeniably talented and skilled, are a good fit for RDT’s performing and creative demands that encompass a continuously expanding multiplicity of movement languages and techniques. “He convinced me early on. His technique improved in leaps and bounds,” Smith says.

Higgins landed a full contract in 2014 and he wasted little time in confronting the expectations for choreographing new work. Watching him create a piece for Emerge, an annual concert held mid-season to highlight new compositions by RDT dancers, Smith says, “I was awestruck. Where did he get that skill as a choreographer? He knew how to move dancers efficiently and effectively and run a rehearsal. He worked stylistically with the music he selected. I definitely needed to keep an eye on him. He absorbed everything.”

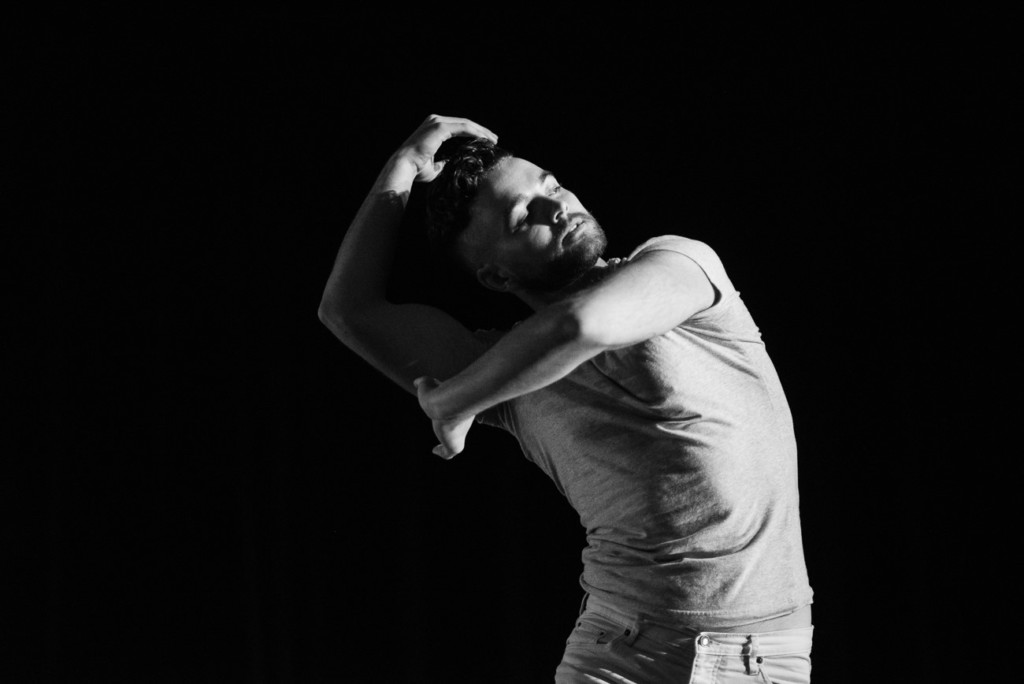

Mindful of the importance of staying humble, Higgins wisely reminds that he is still an emerging choreographer. If there is a thread to be discerned from his initial oeuvre of choreographed compositions, it is how they spring from an inner passion that Higgins then channels to resolve the problem of expressing it clearly enough through his creative choices, both in dance movement and music.

Higgins saw the annual summer Great Salt Lake Fringe Festival as a viable venue to explore the possibilities. In 2016, he set Declivity, a work for 11 dancers – including himself and three RDT dancers – addressing the “fracturing of cross-cultural understanding,” as he described in his program notes. A lovedancemore.org review of the work summarized it as, “Higgins demonstrated good command of the large group throughout space and formations, often negotiating it into solos, duets, and trios seamlessly. Higgins’ movement language was sophisticated in its full physicality threaded with memorable gesture motifs.”

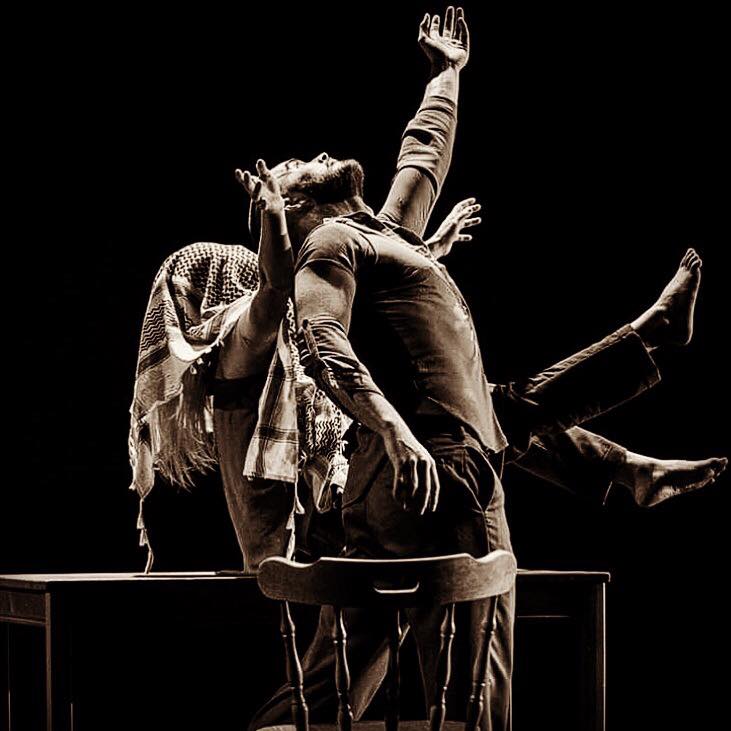

The reviewer [Amy Falls] indicated the work in some respects (such as group formations and musical selections) reminded her of Dabke, a full-length composition which RDT dancers have given exceptional performances. Israeli choreographer Zvi Gotheiner set out to create Dabke (2012), a dance composition inspired by the national dance of Syria and Lebanon that also is an integral aspect of Jordanian and Palestinian cultures as well as Israel and other Middle East countries. In 2018, Higgins was invited by Gotheiner to join ZviDance, his company, for a tour in Colombia, presenting Dabke. Higgins describes it as an “experience of his greatest dreams.”

In 2017, Higgins followed up at the Great Salt Lake Fringe with the work that eventually would become the evening-length In. Memory. Of., presented in 2018 as part of RDT’s Link Series.

The maturing leap from Declivity was astounding. Higgins created the work from his own experience, as the aspects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) have affected his family. Higgins’ late father served in Vietnam with the U.S. Special Forces as a Green Beret and the young artist only learned the whole story of the struggles his father experienced after he died. As he said in a 2018 interview with The Utah Review, Higgins said his father always hid his struggles, convinced that being seen as vulnerable is a sign of human weakness that can never be overcome.

To handle a subject with so many complex emotions and to do so sensitively constituted an objective that required the utmost maturity and confidence as an empathetic artist. To recall the review at The Utah Review, “the dancers were invested emotionally and socially in each other, as colleagues and as performers. But, even more remarkable is that there were many moments in the work, which demanded the dancers to be vulnerable — even impotent and confrontational — toward each other. Off the stage they would never contemplate doing so as artists who respect each other deeply. But it was a critical dynamic that Higgins pushed for in rehearsals and the results proved it.”

Likewise, a panel of therapists specializing in care for veterans joined Higgins and the dancers in a talkback following the performance of In. Memory. Of. They noted how such artistic experiences can begin to help individuals and family members understand and cope with the pain on the path toward healing and breaking away from the illusions of our habitual thinking about psychological trauma and the impacts on mental health.

Lane, who had never seen Higgins perform during his college days but now was familiar with his work at RDT, says, “Dan really grew. When I saw In. Memory. Of. I said, ‘Holy cow!’ I was blown away. It emotionally struck a chord in me.”

Two of the dancers who performed In. Memory. Of. – Micah Burkhardt and Natalie Border – recall the immense personal satisfaction they felt as artists in this collaboration. Burkhardt, who also returns to perform in Speak, Higgins’ latest work, says that working with some choreographers doesn’t always feed his hunger for dance in the way that experiences such as In. Memory. Of. did. “I’m hungry for all that food, metaphorically speaking, “he explains. “But, he also comes ready to tackle all of the ideas and all of us have a direct conversation about making our own connections to what we’re creating.”

Border, who lives in New York City, recalls how much she envied the “unusually intense” physicality and emotions involved with the work and how exciting it was for everyone to join the process and take the risks. Border, who stepped in as a substitute just two weeks before the 2017 Fringe premiere of the original version of In. Memory. Of., said, in a previous interview, it was “amazing to see how this work came from essentially nothing and became a larger piece that reaches out to a community outside of the dance community.”

Burkhardt says he never hesitates to accept an invitation from Higgins to collaborate on a work. For RDT’s 2019 Emerge concert, he performed in a new trio MASC, in which Higgins, Burkhardt and Kaya Wolsey were covered in glitter gold paint. “I was fascinated by this piece because it focused on showing the ugly side of masculinity,” Burkhardt explains. Higgins set MASC to interpret the weariness of sexual objectification and the ever-insistent tribalism of the conventions of masculinity that can be resolved and reconciled in a new path showing that the best way to resolve the tension is to dissolve the boundaries completely. The music parallels the dance sequence perfectly with the relentless pulse of Perera Elsewhere’s Weary, followed by the gritty, dark punk-like industrial sound of Entropy Worship’s Port Holes, and then the anthem-like Luke Howard’s Hymn.

Burkhardt adds that while it took days to remove any remaining flakes of paint from his body, he says that he would still apply the paint if Higgins requested it for a performance. In a reprise last summer at Francisco Gella’s New Century Dance Project in Salt Lake City, Burkhardt assumed the Higgins’ role in MASC, joined by Morgan Phillips and Brendan Rupp, who also are dancing in the work Speak. For that performance, the dancers did not have to apply the paint.

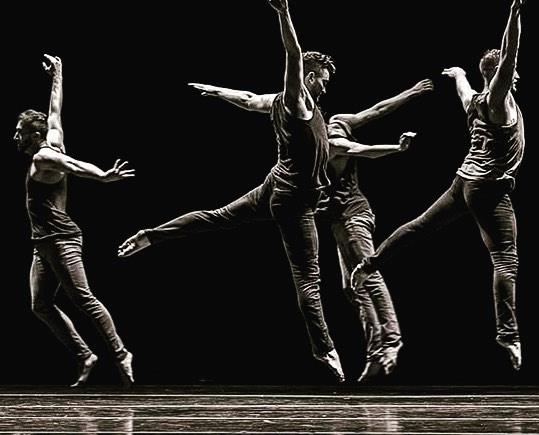

On Facebook and other forms of social media, it has been popular of late to share evidence of what has changed in the last 10 years for each person. A decade ago, Higgins had just decided to make dance the focus of his college career. As 2020 approaches, Higgins is now in his sixth season with the nation’s oldest repertory dance company. He has performed in works by some of modern dance’s greatest choreographers, along with numerous premieres. He and fellow RDT dancer Lauren Curley were the ‘leaders’ in the 1938 warhorse classic Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor, which was restaged by Nina Watt and Jennifer Scanlon. With RDT colleague Tyler Orcutt, he appeared in Alternating Current, a 1982 work by Bill Evans, an internationally renowned choreographer who also danced with RDT during its early years. It was a significant performance, as Evans cast it as a duet which he frequently performed with Gregg Lizenberry, a former partner who also was among the earliest RDT performers. Just a few weeks ago, he and Curley stood out in a premiere performance of a work by Luc Vanier, the founding director of The University of Utah’s School of Dance, set to the famous Allegretto movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. With RDT, he has performed across the country. The opportunity to perform in Medellin, Colombia with the dancers of the internationally renowned ZviDance was unimaginable in his humble days as a new dance student at the University of Wyoming.

Higgins quickly reiterates that he still has much to learn and develop. But, he has joined an impressively enterprising community of dance professionals in Salt Lake City. Next week, he will see the premiere of his third evening-length choreographed composition.With Speak, Higgins and his peers seek to nourish and cultivate their story-telling skills, a point he makes in the following: “In times of despair and sadness, and in times of love and peaceful exuberance, storytelling becomes the method in which we share what we know and feel.”