Y not you, why can’t I—you in this city at closing hour, this strange going

improvised ravine, summer rain among the living.

Y not towards your story, green indecipherable shadows, faces I want

would, longing, to cathedral—

Y not two voices that diminuendo, the point at which what is revealed,

is what leaves— Sean Thomas Dougherty, All I Ask For You Is Longing

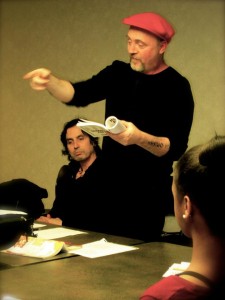

When reading Sean Thomas Dougherty’s work, one often realizes how easily a ‘Dougherty moment’ can pop up — that fleeting moment of a familiar connection, an unexpected yet relevant epiphany about a relationship, event, struggle, love, or pain. A prodigious poet with a vast complex of influences cultivated through an exceptionally voracious appetite for reading, experiences, music and ever-alert observation, he offers up a language rendered, as he explains, in “three dimensions in which we say a word that becomes a form in the air that then is anchored in the space of an exchange between bodies.” There is unflinching realism in his work that the astute reader soon realizes that his poetry and his humanitarianism are among the most worthy American literary descendants of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, whom Dougherty refers to as the father and mother of American poetry.

Dougherty will be performing at this year’s Utah Arts Festival, giving two readings of his work on the Big Mouth Stage (June 27, 6:30 p.m.; June 28, 7 p.m.) and will lead a writing workshop (June 27, 4:30 p.m.). The author of 13 books including All You Ask for is Longing: Poems 1994-2014 (BOA Editions), Scything Grace (2013 Etruscan Press) and Sasha Sings the Laundry on the Line (2010 BOA Editions), he has received several recently honors, including being a finalist for Binghamton University Milton Kessler’s literary prize for the best book by a poet over 40, the prose-poem-novel and his awards include a Fulbright Lectureship to the Balkans, two Pennsylvania Arts Council Fellowships in Poetry and an appearance in Best American Poetry 2014.

In an interview with The Utah Review, Dougherty, 50, talked about how he developed his performance style that is defined by energetic musical rhythms and by treating language as 3-D, that started in his younger days when he was in Boston.”There was poet Patricia Smith, a walking saxophone of sound, and so many cafes where music was driving the scene,” he recalls. His musical influences include Irish music, punk, tango, Colombian, Sufi, Eastern Europe, New Orleans, jazz and funk, and musicians such as John Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix. One of the most significant influences was the late Sekuo Sundiata from East Harlem, who taught at The New School in New York City and mentored and collaborated with Ani DiFranco. “It really changed everything,” he explains. “When I perform, sometimes it’s not what’s on the page. I will jump lines to shape sound textures and switch between slow and fast. I’m interested in the openness of words and their sounds so that their meaning becomes secondary.”

Dougherty’s muse is a complex of his formative history, where he spent his younger years in Brooklyn, Toledo (Ohio), and Manchester (New Hampshire). He comes from a diverse family with an African American stepfather and a mother of mixed European descent. Among his most significant mentors was his grandfather Joseph Kreisler, a Fulbright scholar and later a social worker who worked with homeless youth runaways and founded the school of social work at the University of Southern Maine. In an interview with Bookslut’s Jessa Crispin in 2007, Dougherty said, “What I learned most, though, from my grandfather was to love the world, to struggle for the world because it is our world. I lived with my grandparents when I was small in Brooklyn. When my grandfather took me for walks he would always point out things, point at a balloon let go in the sky, at a one-legged pigeon doing a dance, at a crack in the sidewalk that extended down to China. If we listened we could hear Mao laughing! He would ask me questions. He asked me what I thought, how I felt. He never stopped doing this. … [He] worked his life to make spaces for people to have a cup of coffee and a cigarette. A cup of coffee and a cigarette isn’t much for a man’s life, is it? He said that once. In this country it seems sometimes even that is too much to ask. But he taught me to ask for that and so much more for others.”

Living in Erie, Pennsylvania, a city that struggles persistently with the effects of poverty, Dougherty also works as houseman at Gold Crown Billiards, occasionally giving lessons in pool. Some of his poetry, he says, “is domestically oriented.” His partner Lisa contends daily with the effects of autoimmune illness and then there are the typical issues which any father with children must confront. Perhaps the best sense Dougherty got about how his work has evolved over the last two decades came when he was selecting work for the BOA Editions collection last year. “That was a trip,” he says. “I kept wondering what I was doing back then and some I didn’t like. There seemed to be a lot about obsessions. Today, I’m a lot more complicated person than when I was 25.”

Reading prose and prose poetry is one of his most important conditioning exercises for writing, which has a strong sense of jazz’s improvisational and spontaneous nature. There are Martin Espada, Li Young Lee, Dorianne Laux, Malena Morling, John Yau, Peter Markus, Michard Burkard, the French school of phenomenology, Stratis Haviaras and many, many others. He cites the great Argentine writer Julio Cortázar’s prose poem The Lines from The Hand (which starts, “From a letter thrown on the table a line comes which runs across the pine plank and descends by one of the legs. Just watch, you see that the line continues across the parquet floor, climbs the wall and enters a reproduction of a Boucher painting, sketches the shoulder of a woman reclining on a divan, and finally gets out of the room via the roof and climbs down the chain of lightning rods to the street. …”) “This is it,” he explains, and, indeed, it may be one of the most representative examples of how Dougherty approaches performing his work before an audience.

Unlike some writers who even set aside a period each day to work, Dougherty says he might go six months without writing. “Meanwhile, I’m writing down notes, collage pieces of language or a line of a poetry that I throw into a basket and then I sit down months later and splurge. The process can be very fast — sometimes in an evening or within 24 to 48 hours” he explains, adding it’s a process that has worked for getting four books out to the publisher. He does not hesitate to discard scraps of texts or lines, knowing that he can create more, as needed. Burkard is a key example of this approach, he says. “He would write a poem, stuff it into a jar, and then months later come back to it. He might keep it or discard it. He says it’s a smart way to see if he has caught up to the point of the poem.”

Dougherty feels at ease with this approach. “I am constantly writing, in a sustained production of language. I am constantly gathering and collecting material. Some need to write every day and they become a neurotic mess if they are not.” The point is amplified in a 2013 interview with Justin Bigos: “Too many poets negate the life from the poem. For me the poem is an attempt to make sense of and to communicate the life. To translate it. To offer it in language for someone who may need to hear the simple story that we ‘did not die’. I did not die when I could have, that I did not die when I should have. That I kept going. That along the way many do not. For them we continue the struggle. The poem is simply part of the struggle to live honorably.”